-

After the big bang, the Universe experienced cosmic phase transitions, e.g., the electroweak phase transition at

$ t=10^{-10} $ s around$ T=100 $ GeV and the quantum chromodynamics (QCD) phase transition at$ t=10^{-5} $ s around$ T=150 $ MeV. The cosmic QCD phase transition set the initial conditions for big bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) and is essential to understand the properties of compact stars at high baryon density.Though the peak structure of the sound velocity describing the neutron stars and GWs emitted from binary neutron stars may favor a crossover at high baryon density and low temperature [1], and for physical quark mass, lattice QCD calculations indicate a crossover at high temperature [2] at zero or small chemical potential in 2-flavor and 3-flavor systems [3, 4], a first-order phase transition is of our interest due to intriguing and unique imprints in the early Universe. The first-order QCD phase transition at high temperatures can be found in a massless 3-flavor system [5] as a chiral phase transition, the confinement-deconfinement phase transition in the pure gluon system [5], and Friedberg-Lee model [6−8], as well as in the chirality imbalanced system [9, 10].

The QCD phase transition is also possibly a first-order phase transition at high chemical potential. The high baryon density can be generated through the elegant and well established Affleck-Dine baryogenesis [11−13], which tends to generate dense baryon clumps instead of homogeneous ones in the early Universe, and this high density can be subsequently diluted to the level observed today through the little inflation [14−18]. The high baryon density clumps can be inhomogeneously distributed in the early Universe through first-order electroweak/QCD phase transitions or fluctuations [19−24]. High baryon density clumps, known as the primordial quark nuggets (PQNs), through cosmic QCD phase transitions were proposed by Witten in 1984 [20] and have been investigated from many aspects [21, 25−27]. In particular the strangelet, which is more stable than ordinary nuclear matter, has attracted significant interest. The PQNs proposed by Witten are generated by the remaining and shrinking false vacuum squeezed by the propagation of the true vacuum bubbles. The PQNs only occupy a minute fraction of the Universe but contain 80%−99% of the baryon excess, with a density of

$ 10^{15} $ $ \mathrm{g/cm^3} $ and mass of$ 10^9-10^{18} $ g approximately [20], which corresponds to a size of$ 10^{-2}-10^1 $ cm.A first-order phase transition is also required to produce the stochastic background gravitational waves (SBGWs) in the early Universe. Recent observation results from several pulsar timing array (PTA) collaborations, including the Parkes Pulsar Timing Array (PPTA), North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav) [28, 29], European Pulsar Timing Array (EPTA), and Chinese Pulsar Timing Array (CPTA) [30−34], have independently detected evidence of stochastic GW signals in the nanohertz band. The nanohertz GWs may come from the orbiting or mergers of supermassive (

$ 10^{35}-10^{40} $ kg) black hole binaries [35] or from cosmic phase transitions in the electroweak [36] or QCD epoch [37, 38].The transition rate

$ \beta/H $ , also known as the inverse duration of the phase transition, describes the frequency of the bubble collisions and is a crucial parameter to decide the peak frequency and peak energy density of the GW spectra. Ref. [38] gives a bound$ \beta/H<15 $ for QCD phase transitions to generate nanohertz GWs. In some references,$ \beta/H $ is treated as a free parameter. For example,$ \beta/H $ was taken in the order of$ 1-10 $ for the pure gluon system to produce the nanohertz GWs [39, 40]. However, for typical first-order chiral and confinement phase transitions at high temperature, the bona fide calculations in the low-energy effective QCD-like theories and holographic QCD models give$ \beta/H\sim 10^{4-5} $ [41−45]. The corresponding peak frequency of GWs typically lies in the region of$ 10^{-4}-10^{-2} $ Hz with the power spectrum in the range of$ 10^{-8}-10^{-7} $ , which lies in the ranges of LISA and Taiji.In this study, we investigate the possibility of producing nanohertz GWs from first-order QCD phase transitions, particularly if high baryon density QCD matter can be generated in the early Universe. We will show that the baryon chemical potential can significantly reduce the transition rate, and there exists a narrow window of high baryon chemical potential with the transition rate on the order of

$ \beta/H \sim 10^1 $ to produce nanohertz GWs. There exists a critical nucleation point (CNP), where the bubble nucleation can barely occur and the transition rate is zero$ \beta/H=0 $ . Zero$ \beta/H $ implies that the phase transition from quark matter to hadronic matter cannot be completed; thus, it is possible that primordial ''quarklet'' or PQNs exist in the early Universe. In this short letter, we offer an explanation for the appearance of the CNP and analyze the properties of the PQNs formed by the long-lived false vacuum. -

First-order phase transitions are completed via bubble nucleation. Once the phase transition starts, parts of the Universe jump to true vacuum from false vacuum, forming bubbles with lower vacuum energy density, and then, the released latent heat is converted into the energy of the bubble walls. These bubbles expand and collide and pass kinetic energy to the surrounding media, generating GWs from the collisions of the bubbles, sound waves, and magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) turbulence [46].

The bubble nucleation rate per volume per time has the exponential form

$\Gamma(t)=A{\rm e}^{-S_4(t)}$ [47−49], where$ S_4 $ is the Euclidean action of an$ O(4) $ -symmetric solution and reduces to$ S_3/T $ at high temperature T, and the coefficient A has the form of$ A(T)=T^4(S_3/(2{\pi}T))^{3/2} $ [50]. Here,$ S_3 $ is the bounce action of the field configuration between the false and true vacuum of an$ O(3) $ -symmetric bubble, which can be determined by the equation of motion.Bubbles of the true vacuum start to occur at the nucleation temperature

$ T_n $ , at which the nucleation rate catches the expansion rate of the Universe. In the QCD epoch,$ T_n $ can be quickly estimated by$ S_3/T\sim 180 $ [41, 51, 52]. More precisely, one bubble per Hubble volume per Hubble time$ {\Gamma}(t)/H^4\sim1 $ is expected at$ T_n $ [47, 49], where H is the Hubble parameter given by the Friedmann equation.$ T_n $ is also the approximate temperature of the thermal bath with weak reheating; thus, the transition rate β is defined as$ \frac{\beta}{H}=T_n\left.\frac{\mathrm{d}(\frac{S_3}{T})}{\mathrm{dT}}\right|_{T_n}. $

(1) Another parameter to which the GW spectra are sensitive is α, which quantifies the transition strength, i.e., the relative magnitude of the latent heat released in the phase transition compared to the background radiation energy density

$ \rho_r $ [49, 50]. α can be calculated with finite μ as$ \begin{aligned}[b] \alpha & = \frac{-\Delta\rho+3\Delta p}{4\rho_r} \\ & =\frac{1}{\rho_r}\left(\Delta p-\frac{T}{4}\left.\frac{\partial \Delta p}{\partial T}\right|_{T_p}-\frac{\mu}{4}\left.\frac{\partial \Delta p}{\partial \mu}\right|_{T_p}\right), \end{aligned} $

(2) where Δ is the difference between true and false vacuum.

$ T_p $ is the percolation temperature, and$ T_p{\approx}T_n $ is used when$ \beta/H \gg 1 $ , i.e., the false vacuum decays rapidly and hence the temperature is nearly constant during the phase transition. In specific models, the thermal background is not the perfect ideal gas, and thus, the background radiation energy density$ \rho_r=\dfrac{{\pi}^2gT^4}{30} $ (g is the number of relativistic degrees of freedom) is not accurate, especially when the chemical potential μ cannot be neglected compared with temperature$ \mu\gtrapprox T $ . Instead, the thermal energy density is given by the effective grand potential$ \Omega=-p $ $ \rho=-(p-p_{\rm vac})+\left.T_n\frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right|_{T_n}+\mu \frac{\partial p}{\partial \mu}, $

(3) where

$p_{\rm vac}$ is the vacuum pressure at$ T=\mu=0 $ and must be deducted.The energy from bubble collisions is negligibly small for relativistic bubbles [53], and only two dominant sources, i.e., the sound waves and MHD turbulence, contribute to the total GW spectra:

$ h^2{\Omega}=h^2{\Omega}_{sw}+h^2{\Omega}_{tb}. $

(4) In terms of the parameters above, the numerical results of GWs from the sound waves and MHD turbulence take the forms of [50, 53]

$ h^2{\Omega}_{sw}(f)=2.65\times10^{-6}\left(\frac{H}{\beta}\right)\left(\frac{\kappa_v\alpha}{1+\alpha}\right)^2\left(\frac{100}{g}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}v_wS_{sw}(f) $

(5) and

$ h^2{\Omega}_{tb}(f)=3.35\times10^{-4}\left(\frac{H}{\beta}\right)\left(\frac{\kappa_{tb}\alpha}{1+\alpha}\right)^2\left(\frac{100}{g}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}}v_wS_{tb}(f), $

(6) respectively. Parameters

$ \kappa_v $ and$ \kappa_{tb} $ are the fraction of the vacuum energy converted into the kinetic energy of the plasma and the MHD turbulence, respectively, which can be analytically fitted [53−55]. The GW spectra are not sensitive to a relativistic bubble velocity$ v_w $ . Thus, in our following calculations, we take a good approximation$ v_w=\dfrac{\sqrt{1/3}+\sqrt{\alpha^2+2\alpha/3}}{1+\alpha} $ for strong phase transitions.$ S_{sw}(f) $ and$ S_{tb}(f) $ have the power-law forms$ S_{sw}(f)=\left(\frac{f}{f_{sw}}\right)^3\left(\frac{7}{4+3\left(\dfrac{f}{f_{sw}}\right)^2}\right)^{\frac{7}{2}}, $

(7) $ S_{tb}(f)=\left(\frac{f}{f_{tb}}\right)^3\left(1+\frac{f}{f_{tb}}\right)^{-\frac{11}{3}}\left(1+\frac{8{\pi}f}{H}\right)^{-1}. $

(8) The peak frequencies are

$ f_{tb} = 1.42f_{sw}=\dfrac{16.36}{v_w}\dfrac{\beta}{H}h $ , where$ h=1.65\times10^{-8}\dfrac{T_n}{1{\rm{GeV}}}(\dfrac{g}{100})^{\frac{1}{6}} $ Hz is the Hubble rate.In the following, we investigate the GW spectra induced by the first-order deconfinement phase transition and chiral phase transition at high baryon chemical potentials by using two simple but representative models: the Friedberg-Lee (FL) model and quark-meson (QM) model, which can reveal the main features of the GW spectra induced by QCD phase transitions.

-

The FL model provides a dynamical mechanism to confine quarks inside the nucleon by a complicated nonperturbative vacuum. It is described by the interaction of a phenomenological scalar field ϕ and quark field Ψ [6−8], and the Lagrangian takes the form of

$ \mathcal{L}_{\rm FL}=\bar\Psi({\rm i} \not \partial -g \phi)\Psi+\frac{1}{2}\partial_\mu\phi\partial^\mu\phi-U_{\rm FL}(\phi). $

(9) Here, the potential

$U_{\rm FL}(\phi)$ is of the Ginzburg-Landau type with a quartic form$U_{\rm FL}(\phi)=\dfrac{1}{2!}a\phi^2+\dfrac{1}{3!}b\phi^3+\dfrac{1}{4!}c\phi^4$ .In the following numerical calculations, we fix four parameters

$ a=0.68921 $ GeV$ ^2 $ ,$ b=-287.59 $ GeV,$ c= $ 20000, and$ g=12.16 $ , as in Ref. [56], to successfully reproduce the static properties of the nucleon.Including the one-loop contribution, the effective grand potential at finite temperature and quark chemical potential is [57, 58]

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Omega_{\rm FL}=\;&U_{\rm FL}(\phi)+T\int \frac{{\rm d}^3\vec p}{(2\pi)^3}\left\{{\rm{ln}} (1-{\rm e}^{-E_{\phi}/T})\right.\\ &\left.-\nu\left[{\rm{ln}} (1+{\rm e}^{-(E_{\Psi}-\mu)/T})+ {\rm{ln}} (1+{\rm e}^{-(E_{\Psi}+\mu)/T})\right]\right\} \end{aligned} $

(10) with

$ \nu=2N_fN_c=12 $ and$ E_i=\sqrt{p^2+m_i^2} $ $ (i=\phi,\Psi) $ . The effective mass of the quark is$ m_{\Psi}=g\phi $ , and that of the scalar field is$ m^2_{\phi}=a+b\phi+\dfrac{c}{2}\phi^2 $ . The order parameter ϕ can be determined by solving the gap equation${\partial\Omega}_{\rm FL}/{\partial\phi}=0$ .The FL model can be used to describe a deconfinement phase transition. At

$ T<T_c $ , there exists a soliton solution serving as a ''bag" to confine the quarks, while there is only a damping oscillation solution at$ T>T_c $ , where the quarks are set free. -

The chiral phase transition can be described by the QM model, and the Lagrangian of the two-flavor QM model has the form [59, 60]

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \mathcal{L}_{\rm QM}=\;&\frac{1}{2}\partial^{\mu}\sigma\partial_{\mu}\sigma+\frac{1}{2}\partial^{\mu}\vec\pi\partial_{\mu}\vec\pi \\ &+ \bar\Psi {\rm i}\not \partial \Psi-g\bar\Psi(\sigma+{\rm i} \gamma_5\vec\tau\cdot\vec\pi)\Psi-U_{QM}(\sigma,\vec\pi). \end{aligned} $

(11) The potential is

$U_{\rm QM}(\sigma,\vec\pi)=\dfrac{\lambda}{4}(\sigma^2+\vec\pi^2-v^2)^2-H\sigma$ , with$ \Psi=(u,d) $ and$ \vec\tau $ being the Pauli matrices. The interaction between the quarks and scalar mesons contains three terms of the pions$ \vec\pi $ and one of the σ meson.The effective grand potential in the QM model is

$ \begin{aligned}[b] &\Omega_{\rm QM}=U_{\rm QM}(\sigma,\vec\pi)-\nu\left\{\int\frac{{\rm d}^3\vec p }{(2\pi)^3}E+\right.\\&\left.T\int\frac{{\rm d}^3\vec p}{(2\pi)^3}\left[\mathrm{ln}(1+{\rm e}^{-(E-\mu)/T})+\mathrm{ln}(1+{\rm e}^{-(E+\mu)/T})\right]\right\} \end{aligned} $

(12) with

$ E=\sqrt{\vec{p}^2+m_q^2} $ .The chiral symmetry is spontaneously broken in vacuum, and σ takes a nonzero vacuum expectation value

$ \sigma=f_{\pi}=93 $ MeV. The effective quark mass is$ m_q=gf_{\pi} $ with$ g=3.3 $ , where we have assumed that$ m_q $ contributes to one-third of the mass of the nucleon. The partial conservation of the axial current gives the parameter$ H=f_{\pi}m^2_{\pi} $ with pion mass$ m_{\pi}=138 $ MeV in the case of nonzero current quark mass. The order parameter can be solved from the gap equation${\partial\Omega}_{\rm QM}/{\partial\sigma}=0=0$ . -

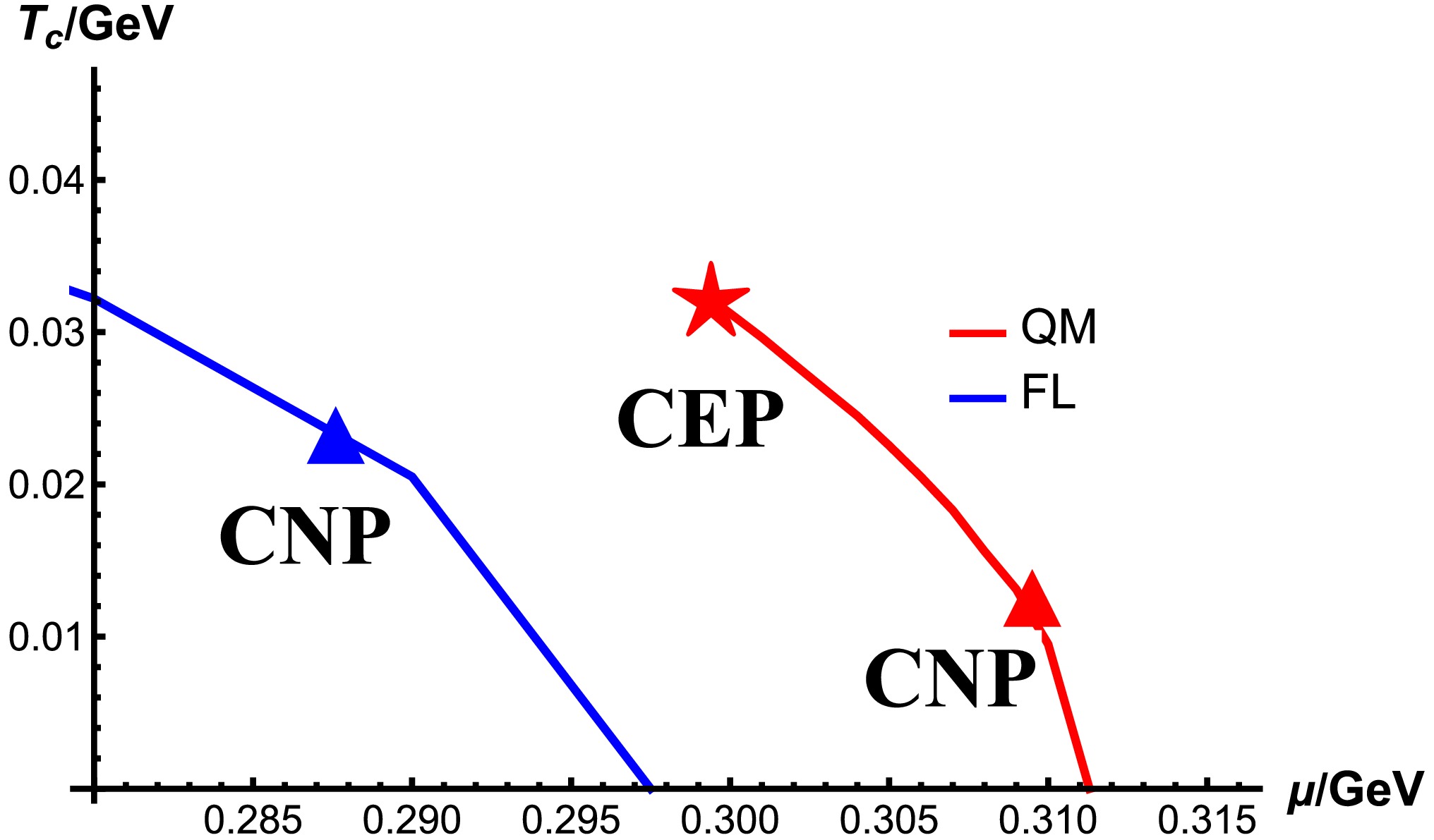

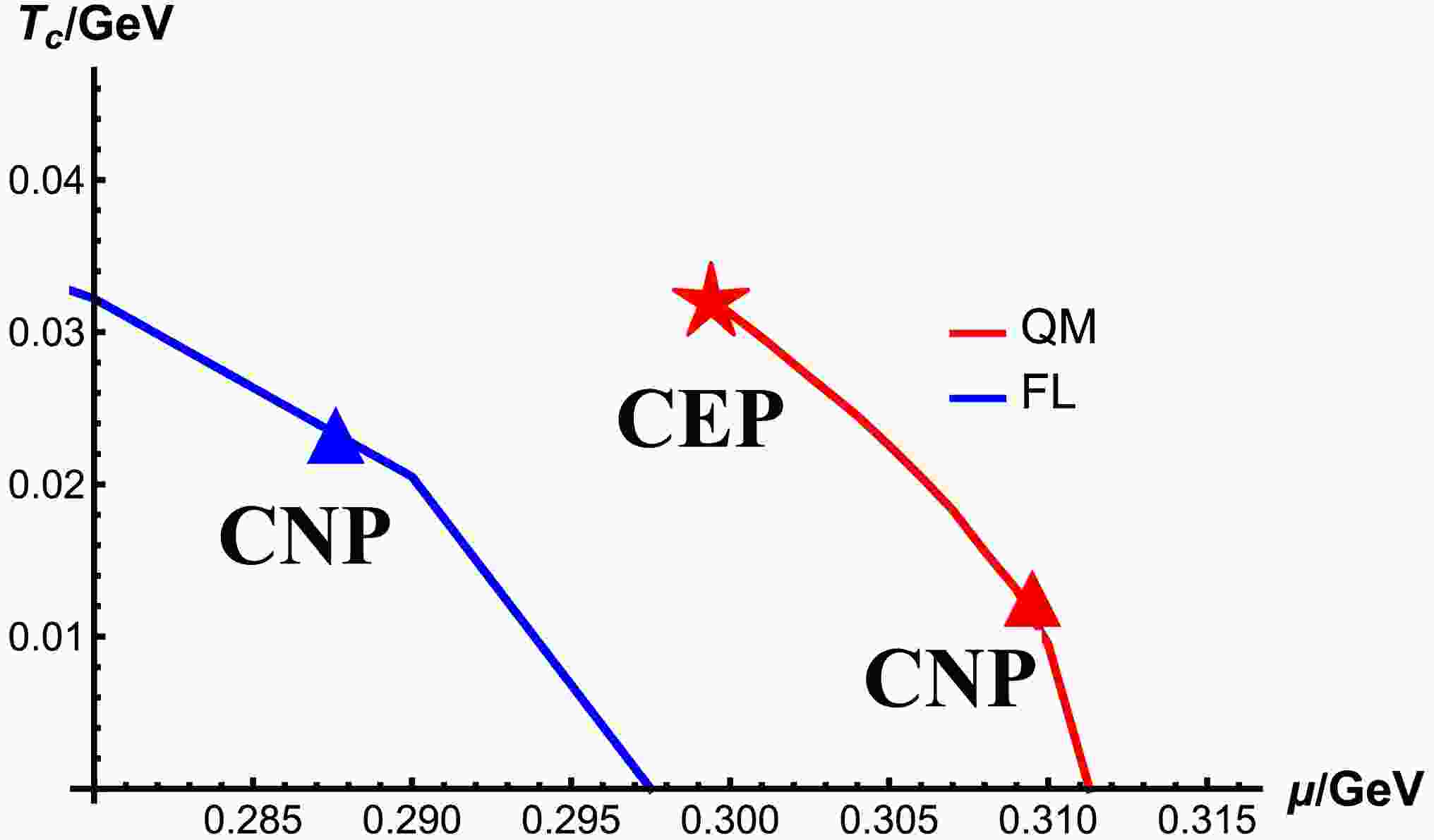

The phase diagrams of the FL and QM models are shown in Fig. 1. The phase transition of the FL model is always of first-order from zero chemical potential to the critical chemical potential

$ \mu_c=297.5 $ MeV, and no CEP exists ($ \mu_E=0 $ ), while the chiral transition in the QM model is a crossover in the low chemical potential region and of first-order in the high chemical potential region until$ \mu_c=311.3 $ MeV. Thus, there exists a CEP located at$ T_E=32.17 $ MeV,$ \mu_E=299.4 $ MeV in the QM model, as indicated by the red star. The triangles indicate the CNPs where the nucleation of bubbles can barely occur. The blue one at$ \mu=287.55 $ MeV is for the FL model, and the red one at$ \mu=309.6 $ MeV is for the QM model.

Figure 1. (color online)

$ T-\mu $ phase diagrams of the FL and QM models. The red star is for the CEP at$ \mu=299.4 $ MeV in the QM model, and triangles are for the CNPs at$ \mu=309.6 $ MeV in the QM model and$ \mu= 287.55 $ MeV in the FL model.$ T_c $ approaches$ 0 $ at$ \mu=311.3 $ MeV in the QM model and$ \mu=297.5 $ MeV in the FL model.The transition rates in the FL and QM models are shown in Fig. 2, with the rescaled chemical potential

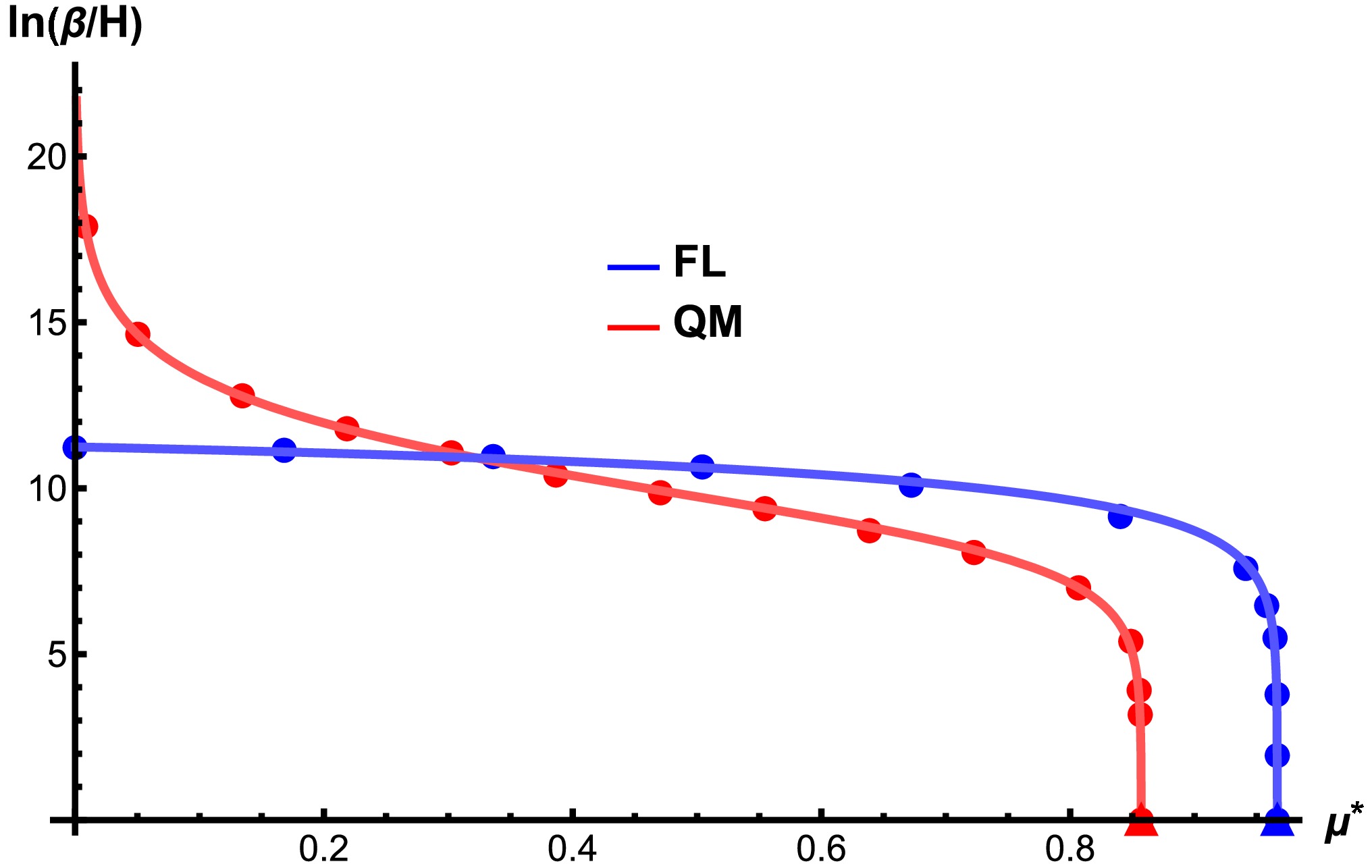

Figure 2. (color online)

$ \beta/H $ with different rescaled chemical potential$ \mu^*=(\mu-\mu_E)/(\mu_c-\mu_E) $ in the FL (blue) and QM (red) models.$ \mu^*=(\mu-\mu_E)/(\mu_c-\mu_E). $

In the FL model, values of

$ \beta/H $ decrease from$ 10^5 $ to$ 10^3 $ when μ increases from$ 0 $ to$ 280 $ MeV and sharply fall from$ 10^3 $ to$ 0 $ in a very narrow window of the chemical potential. The transition rate drops to$ 0 $ before$ \mu_c $ , corresponding to the CNP where$ \mu_{\rm CNP}=287.55 $ MeV, as marked by the blue triangles in Figs. 1 and 2.In the QM model, it is found that the transition rate is almost infinitely close to the CEP. A straightforward reason for this is that the potential barrier barely appears near the CEP, and thus, the transition is ephemeral like a crossover.

$ \beta/H $ starts to fall from infinity from the CEP when the chemical potential μ increases and soon reaches a plateau while$ \beta/H $ varies from$ 10^4 $ to$ 10^3 $ in the region of$ 309 $ MeV$ >\mu>306 $ MeV and sharply falls from$ 10^3 $ to$ 0 $ in a very narrow interval near the CNP$\mu_{\rm CNP}=309.6$ MeV, as marked by the red triangles in Figs. 1 and 2.For the GW spectra, we select some specific values of chemical potential

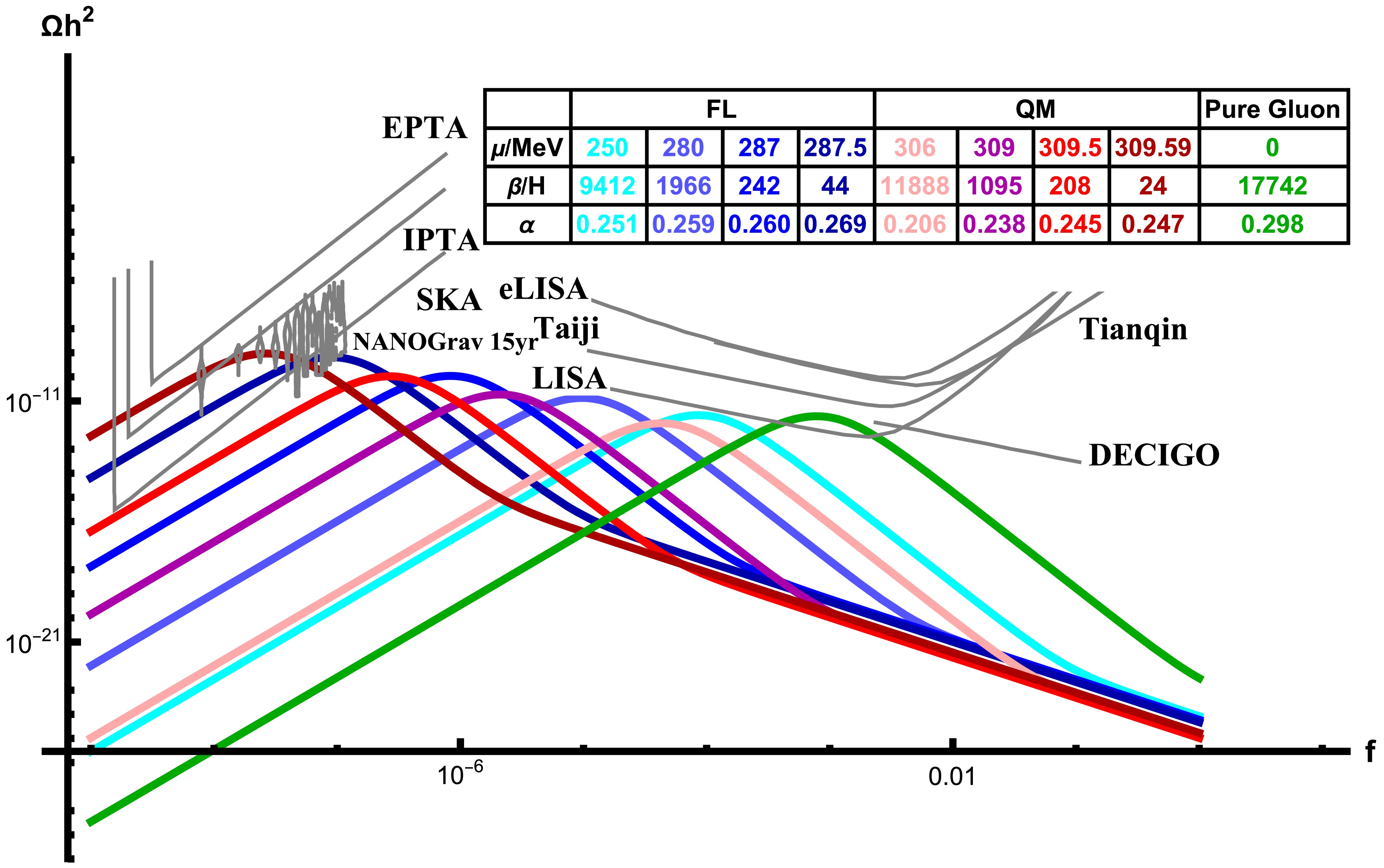

$ \mu=306 $ ,$ 309 $ ,$ 309.5 $ ,$ 309.59 $ MeV in the QM model and$ \mu=250 $ ,$ 280 $ ,$ 287 $ ,$ 287.5 $ MeV in the FL model, which correspond to the magnitude of$ \beta/H $ on the order of$ 10^4 $ ,$ 10^3 $ ,$ 10^2 $ , and$ 10 $ , respectively, and the values of the phase transition strength α are also calculated. These parameters are shown in the table inserted in Fig. 3 as well as the GW spectra, and the pure gluon system at zero chemical potential [61] is used as a reference.

Figure 3. (color online) GW spectra from first-order phase transitions in the FL and QM models with different chemical potential. The pure gluon system at zero chemical potential is used as a reference.

Note that, in the pure gluon system without the quark chemical potential, we have

$ \beta/H\sim 10^4 $ , and the produced GWs fall in the LISA detection window. When the chemical potential increases, the transition rates in the FL and QM models decrease significantly, and the produced GWs move to a lower frequency. In the high baryon density region with$ \mu/T\sim 10 $ , the transition rate$ \beta/H $ can reach the order of$ 10^1 $ , and the produced nanohertz GWs can be detected by SKA, IPTA, and EPTA, coinciding with the NanoGrav data. -

It has been observed that there is an interesting property of the phase transition rate or decay rate of the false vacuum at high baryon density. We provide an explanation here.

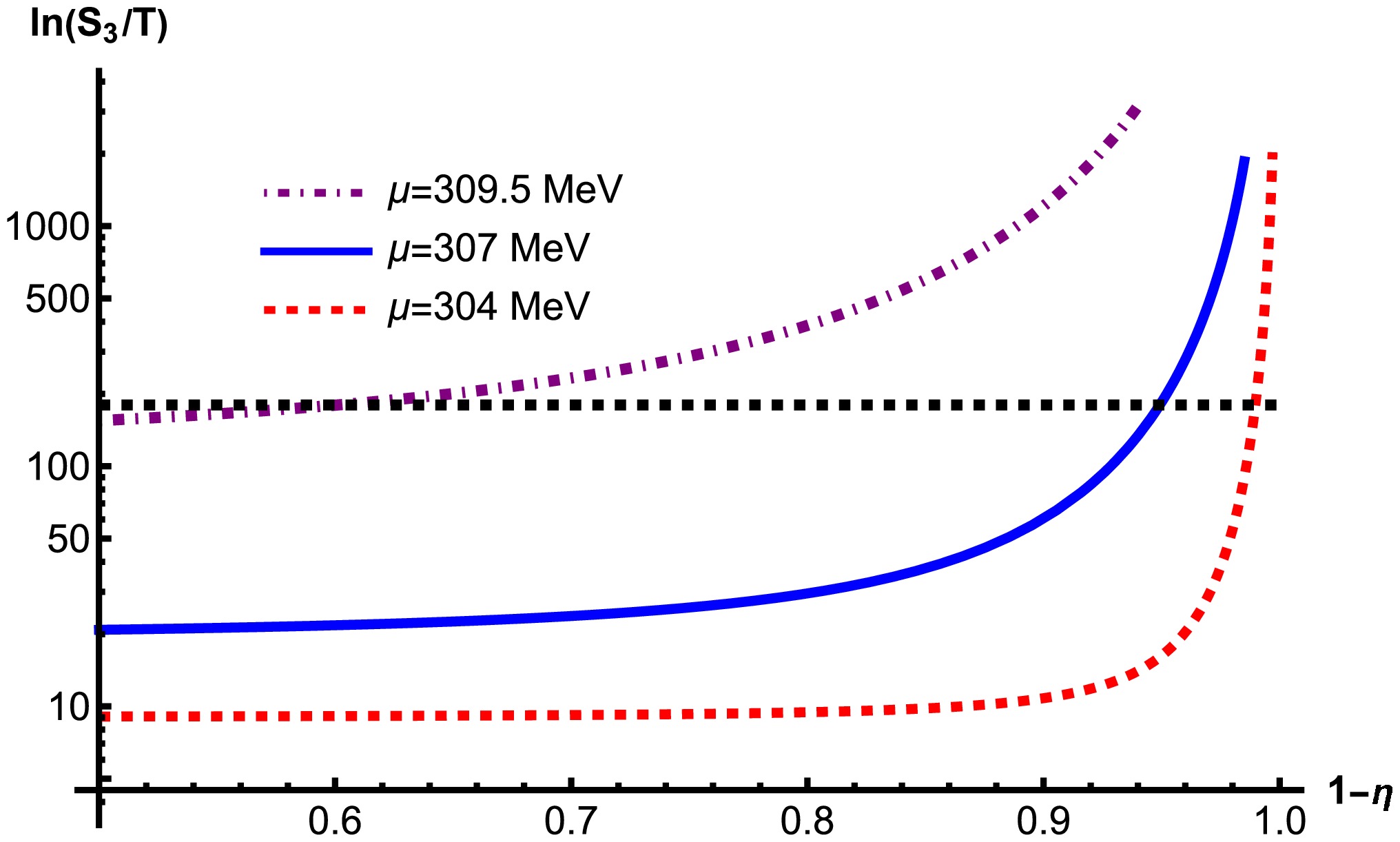

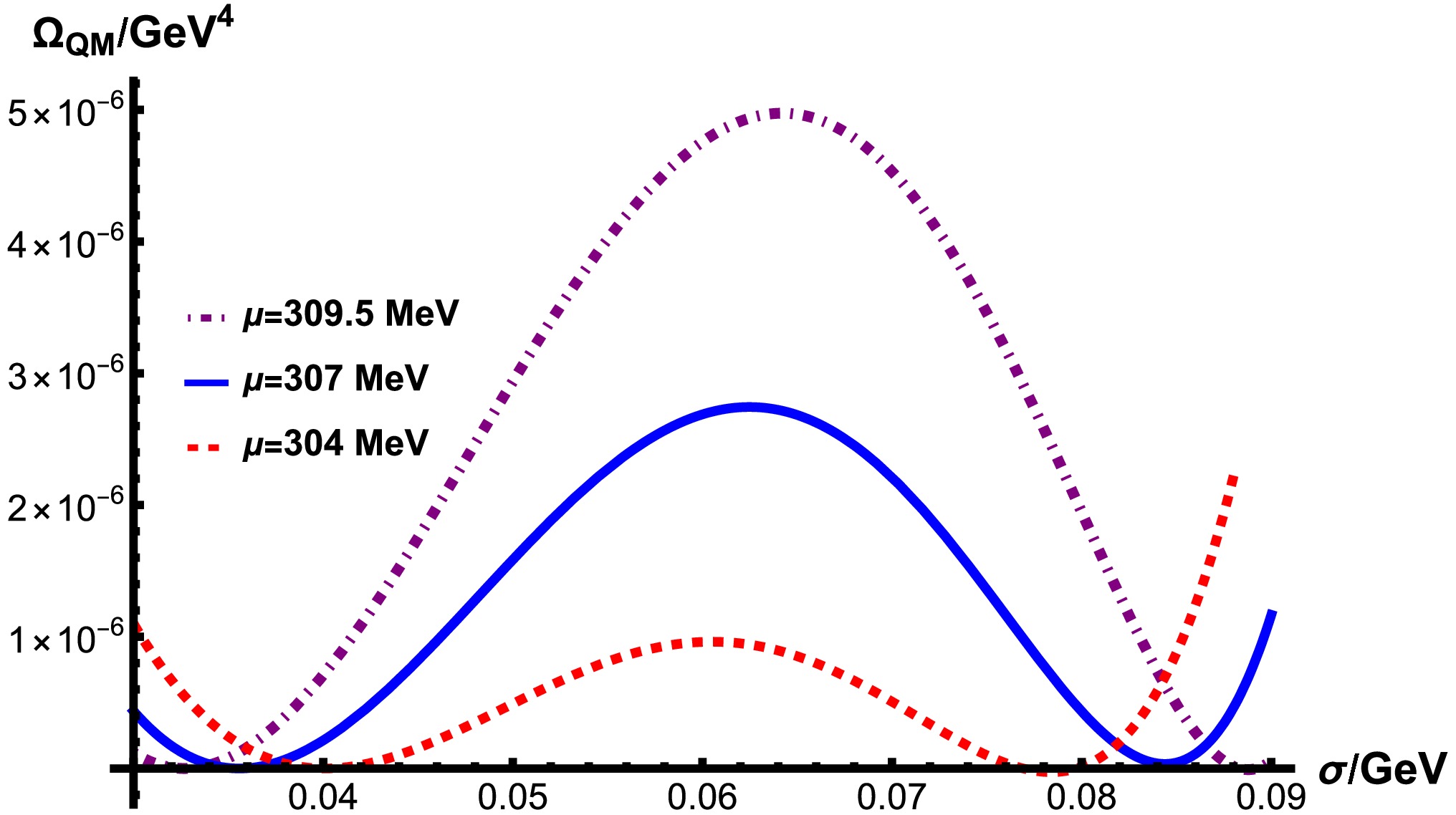

As shown in Fig. 4, where the QM model is taken as an example, a larger chemical potential μ results in a larger bounce action for the same supercooling and a smaller transition rate in the same model. In other words, a larger μ leads to a slower phase transition and lower peak frequency of the GW spectra. The influence of μ can be understood in an intuitive manner, stemming from the experience in the Nambu–Jona–Lasinio (NJL) model. A repulsive vector interaction effectively generates a chemical potential, e.g., see Refs. [62−64]. This can be extended to treat μ as an effective repulsive vector interaction, which creates a potential barrier. As the chemical potential increases further, the potential barrier will be raised, and the system will experience a stronger first-order phase transition. The changes of the potential barrier as the chemical potential μ increases are shown in Fig. 5. When the potential barrier is so high that the false vacuum is unlikely to decay despite two degenerate vacua, the system reaches the CNP. Therefore, the false vacuum of quark matter cannot decay and persists as the PQNs over cosmological time scales.

Figure 4. (color online)

$ S_3/T $ with different chemical potential μ in the QM model. The black dashed line is for 180. Supercooling is defined as$ \eta=1-\dfrac{T}{T_c}. $ These PQNs are different from those proposed by Witten in 1984. In Ref. [20], during a completable first-order phase transition, there exists some sites at which the false vacuum statistically does not decay and the false vacuum is squeezed by the true vacuum bubbles until the formation of quark matter droplets. The size of the PQNs can be estimated by assuming the amount of nucleation during the phase transition and assuming the baryon excess they contain [20, 65]. The droplets of ud quark matter or stranglets with the s quark are possibly more stable than normal nuclear matter [20, 66, 67] with lower energy per baryon number than the normal nucleon considering the strong, weak, and electromagnetic interactions and can act as exotic nuclei [68]. In this study, the PQNs with high chemical potential are generated before the QCD phase transition by Affleck-Dine baryogenesis and, on the contrary, prefer a first-order phase transition during which the bubble nucleation cannot start to persistently survive. Meanwhile, the PQNs are not immortal unless the chemical potential is as large as

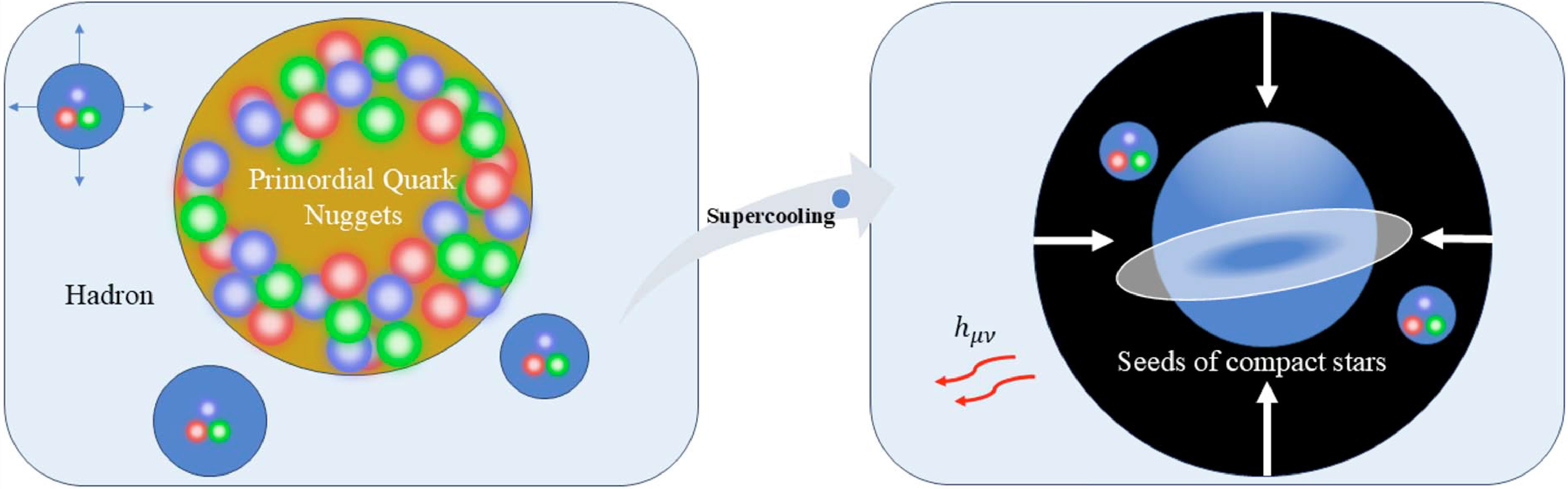

$ \mu_c $ and will not be diluted. If$ \mu>\mu_c $ , the quark matter is more stable than the hadrons with lower vacuum energy, and if$\mu_c > \mu > \mu_{\rm CNP}$ , the quark matter is metastable but does not decay immediately due to the high potential barrier. The size of the PQNs is not constrained by the phase transition itself, and the false vacuum will eventually decay to normal nuclear matter at very low temperature due to quantum nucleation. Therefore, resembling the electroweak phase transitions with extreme super cooling mechanism to produce the nanohertz GWs [36, 69−72], these persistent dense nuggets will decay at an extremely slow rate at very low temperature. Because of a slow phase transition, nanohertz GWs may also be generated later and inhomogeneous remaining cold matter may collapse into primordial black holes [73]. The long-lived false vacuum can also survive as seeds of compact stars, dramatically accelerating the evolution of compact stars as well as the formation of galaxies. Thus, it is possible for the long-lived false vacuum in the compact structures partly formed by the PQNs to slowly decay to normal matter and leave cosmic implications. This scenario is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6. (color online) The left panel shows that the chiral phase transition occurs in the background, while the PQNs remain in the early Universe. The right panel shows that the chiral phase transition finally occurs inside the PQNs slowly after further supercooling. Due to the imhomogeneity from the slow phase transition, the PQNs serve as the seeds of compact stars or galaxies and sources of GWs.

-

Many effective QCD model calculations have shown that first-order QCD phase transitions at high temperatures are characterized by a large transition rate with a magnitude of

$ \beta/H \sim 10^4 $ , and the GWs typically fall within the LISA detection window. In this study, we investigated the possibility of producing nanohertz GW spectra from first-order deconfinement and chiral phase transitions using two simple yet representative models, i.e., the FL and QM models, at high baryon chemical potential.Our studies show that the baryon chemical potential enhances the potential barrier between the false and true vacuum and can significantly reduce the transition (or decay) rate. The decay rate is infinite at the CEP and drops to zero at the CNP. Nanohertz GWs can be produced in a narrow window of high baryon chemical potential when the transition rate is on the order of

$ \beta/H \sim 10^1 $ . When the chemical potential is larger than$\mu_{\rm CNP}$ , the false vacuum is unlikely to decay and can persist over cosmological time scales. These remaining PQNs differ from the PQNs or strangelets proposed by Witten in 1984.Furthermore, the PQNs will become the seeds of compact stars or structures, which may help to explain the high red-shift massive galaxies observed by the James Webb Space Telescope. The PQNs can survive at the low temperature at which vacuum decay prevails over thermal decay. The corresponding phase transition will eventually occur due to the quantum effect at an extremely slow rate, turning dense quark matter into normal baryon matter and possibly generating nanohertz GWs and inhomogeneity. The phase transition is likely to erupt most parts of the baryon matter with a cold sparse core remaining. Ejected matter is likely to form halos around central matter or disperse around, forming structures. In addition, secondary signals, such as electromagnetic and gravitational radiation from accretion, might be observed in the late Universe. Our results can be extended straightforwardly to high density QCD-like dark matter [65], and the corresponding PQNs may constitute dark matter [74].

It is worth mentioning that considering diquark condensation, i.e., the color superconducting phase at high baryon density [75−77], the first-order phase transition line at high μ and low temperature might be changed. Furthermore, the effect from the (primordial) magnetic field in the QCD phase transition should be taken into account in the future [78, 79].

-

We thank Y.D. Chen, F. Gao, and J. Schaffner-Bielich for helpful discussions.

Nanohertz gravitational waves and primordial quark nuggets from dense QCD matter in the early Universe

- Received Date: 2025-02-07

- Available Online: 2025-06-15

Abstract: Affleck-Dine baryogenesis generated high baryon density in the early Universe. The baryon chemical potential enhanced the potential barrier and significantly reduced the decay rate of false vacuum, which decreased from infinity at the critical end point to zero at the critical nucleation point. When the decay rate reached zero, the false vacuum of high baryon density quark matter was unlikely to decay and could persist over cosmological time scales. Therefore, primordial quark nuggets (PQNs) could form and survive in the early Universe as the seeds of compact stars. This new mechanism for the formation of PQNs is different from Witten's stable droplet of quark matter.

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: