-

Hypernuclear systems constitute an important research topic in nuclear physics. Relevant studies have been conducted in production, decay, and structure of hypernuclei. Various theoretical approaches have also been proposed to investigate different aspects of the nature of hypernuclei, such as the generator coordinate method (GCM) [1, 2], orthogonality condition model [3−5], Tohsaki-Horiuchi-Schuck-Röpke (THSR) wave function [6−9], variational Monte Carlo (VMC) method [10], Gaussian expansion method [11−18], cluster orbit shell model [19], particle rotor model [20], and mean-field approaches [21−33].

In hypernuclear physics, one of the main aspects is to study new dynamical and structural properties resulting from the addition of a hyperon (or few hyperons). Because of the absence of the Pauli principle between nucleons and the hyperon, participation of the hyperon in nuclei leads to a stronger effect of attraction and thus possibly more bound states, which may change the location of the drop line. Consequently, the contraction of the nuclear cores becomes significant. Such phenomena are jointly known as ‘glue-like’ role of the hyperon. The systematic study of the binding energy of light single hyperon-hypernuclei has traditionally been a key research topic for stable nuclei and neutron-rich nuclei plus hyperons.

Another important research topic in hypernuclear physics is the hyperon-nucleon and hyperon-nucleus scattering processes, aiming to find new resonant states due to the injection of the hyperon. To address resonance problems, many theoretical approaches have been proposed and applied successfully to handle resonant states and scattering processes, such as the R-matrix method [34−38], complex scaling method (CSM) [39−48], complex momentum representation (CMR) [49−54], trap method [55−66] and absorbing boundary conditions method [67−72].

As a mean-field approach, the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock (SHF) method [27−33] is based on the self-consistent Hartree-Fock equations and uses the Skyrme potential for the nucleon-nucleon interaction. It has been successfully applied to the study of nuclear structures, deformation, energy spectrum, etc. By extending SHF with various hyperons, it has also been effectively utilized in hypernuclear research. For light hypernuclei, in addition to few-body methods and microscopic cluster models, SHF can still be effective when one is interested in the binding energy of hyperons. In this case, the deviations arising from the limitations of the mean-field approximation and corresponding inadequate description of nuclear parts are partially compensated [29], allowing SHF to be applied across a wide mass range, from light to heavy hypernuclei.

In this study, we combined the SHF method with complex momentum representation to address the resonant state problem of spherical nuclei plus single Λ hyperon. Hyperon scattering experiments are crucial for investigating and understanding hyperon-nucleon and baryon-baryon interactions. Although experimental data related to hyperon-nucleus scattering is currently lacking, we have derived some predictions for these experimental data based on our theoretical methods.

In particular, we combined CMR with continuum level density (CLD) [38, 73, 74] to calculate the scattering phase shifts between a hyperon and a nuclear core and extract the scattering length from the scattering phase shifts obtained from CMR-CLD based on effective range expansion [75, 76]. The numerical results obtained through our methods show good consistency with those from traditional methods, thereby providing valuable insights for studying resonance and scattering in hypernuclei within the mean-field and complex momentum representation frameworks.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. In Sec. II, we first formulate the SHF framework incorporating hyperons. Next, we present the theoretical frameworks for complex momentum representation, CLD, and effective range expansion. In Sec. III, the numerical results for single Λ hyperon and spherical nuclear core scattering are presented and discussed. Sec. IV summarizes the article.

-

The total energy of a single-hyperon hypernucleus can be expressed as [77–79]

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} E=\int \mathrm{d}^3 \boldsymbol{r} \varepsilon(\boldsymbol{r}), \quad \varepsilon=\varepsilon_{N N}+\varepsilon_{\Lambda N}, \end{array} $

(1) where

$ \varepsilon_{N N} $ and$ \varepsilon_{\Lambda N} $ account for the nucleon-nucleon and hyperon-nucleon interactions, respectively. The energy-density functional depends on the one-body density$ \rho_{q } (\boldsymbol{r}) $ , kinetic density$ \tau_{q } (\boldsymbol{r}) $ , and spin-orbit current$ \boldsymbol{J}_q (\boldsymbol{r}) $ ,$ \begin{aligned}[b] \rho_q (\boldsymbol{r} ) =\;&\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_q} n_q^i\left|\phi_q^i(\boldsymbol{r} ) \right|^2, \\ \tau_q (\boldsymbol{r} ) =\;&\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_q} n_q^i\left|\nabla \phi_q^i(\boldsymbol{r} ) \right|^2, \\ \boldsymbol{J}_q (\boldsymbol{r} ) =\;&\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_q} n_q^{i} \phi_q^{i\ast}\left(\nabla \phi_q^i(\boldsymbol{r} ) \times \sigma\right) / i, \end{aligned} $

(2) where

$ \phi_q^i $ (i = 1, 2, ...,$ N_q $ ) are self-consistently calculated single-particle wave functions of the$ N_q $ occupied states for different particles, namely q =n,$ p, $ and Λ. They satisfy the Schrödinger equation, obtained by minimization of the total energy functional (Eq. (1)) according to the variational principle,$ \left[\nabla \cdot \frac{1}{2 m_q^*(\boldsymbol{r})} \nabla-V_q(\boldsymbol{r})+{\rm{i}} \boldsymbol{W}_q(\boldsymbol{r}) \cdot(\nabla \times \boldsymbol{\sigma})\right] \phi_q^i(\boldsymbol{r})=e_q^i \phi_q^i(\boldsymbol{r}), $

(3) where

$ \boldsymbol{W}_q(\boldsymbol{r}) $ is the spin–orbit interaction part for the nucleons, as reported in Refs. [80]. The spin-orbit force for the Λ hyperon is very small [81, 82] and was ignored in this study. The central mean-fields$ {V}_q(\boldsymbol{r}) $ , corrected by the effective-mass terms following the procedure described in Refs. [77, 79] are$ \begin{aligned}[b] V_N=\; & V_N^{\mathrm{SHF}}+\frac{\partial \varepsilon_{N \Lambda}}{\partial \rho_N} \\ & +\frac{\partial}{\partial \rho_N}\left(\frac{m_{\Lambda}}{m_{\Lambda}^*\left(\rho_N\right)}\right)\left(\frac{\tau_{\Lambda}}{2 m_{\Lambda}}-\frac{3}{5} \frac{\rho_{\Lambda}\left(3 \pi^2 \rho_{\Lambda}\right)^{2 / 3}}{2 m_{\Lambda}}\right), \end{aligned} $

(4) $ V_{\Lambda}=\frac{\partial\varepsilon_{N \Lambda}}{\partial \rho_{\Lambda}}-\left(\frac{m_{\Lambda}}{m_{\Lambda}^*\left(\rho_N\right)}-1\right) \frac{\left(3 \pi^2 \rho_{\Lambda}\right)^{2 / 3}}{2 m_{\Lambda}} . $

(5) The Skyrme force SLy5 [83, 84] is used for the nucleon-nucleon interaction

$ \varepsilon_{N N} $ , and the hyperon-nucleon interaction$ \varepsilon_{N \Lambda} $ is parameterized as follows (densities ρ given in units of fm$ ^{-3} $ ; energy density ε given in MeV fm$ ^{-3} $ ):$ \begin{aligned}[b] \varepsilon_{N \Lambda}\left(\rho_N, \rho_{\Lambda}\right)=\; & -\left(\varepsilon_1-\varepsilon_2 \rho_N+\varepsilon_3 \rho_N^2\right) \rho_N \rho_{\Lambda} \\ & +\left(\varepsilon_4-\varepsilon_5 \rho_N+\varepsilon_6 \rho_N^2\right) \rho_N \rho_{\Lambda}{ }^{5 / 3}, \end{aligned} $

(6) together with

$ \frac{m_{\Lambda}^*}{m_{\Lambda}}\left(\rho_N\right) \approx \mu_1-\mu_2 \rho_N+\mu_3 \rho_N^2-\mu_4 \rho_N^3 . $

(7) The parameters

$\varepsilon_{1},\varepsilon_{2},...,\varepsilon_{6}$ in Eq. (6) and the Λ effective-mass$ \mu_i $ were determined in BHF calculations with the Nijmegen potential NSC97f [79, 85]. -

The nuclear cores considered in this study are almost spherical and their deformation can be neglected. Therefore, the single-channel Schrödinger equation in momentum representation can be expressed as follows:

$ \dfrac{\hbar^2k^2}{2\mu}\phi(k)+\int V_l(k,k')\phi(k')k'^2{\rm d}k'=E\phi(k), $

(8) where the reduced mass

$ \mu=\dfrac{Am_N m_{\Lambda}}{Am_N+m_{\Lambda}} $ , with A being the nucleon number of the nuclear core, the nucleon mass$ m_N $ being equal to 938.918 MeV, and the Λ hyperon mass$ m_{\Lambda} $ being equal to 1115.683 MeV. The potential in momentum space$ V_l(k,k') $ is obtained by the spherical potential$ V(r) $ extracted from the SHF method:$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} V_l(k,k')=\dfrac{2}{\pi}\int j_l(kr)V(r)j_l(k'r)r^2{\rm d}r, \end{array} $

(9) where

$ j_l $ represents the spherical Bessel function. Although the doubly-magic core nuclei considered in this study exhibit deformation experimentally, the deformation is relatively small and these core nuclei can be regarded as near-spherical nuclei. Therefore, we introduced a spherical hyperon-nucleus interaction$ V(r) $ in our theoretical framework. When deformation cannot be neglected, Eq. (8) becomes a coupled equation.As previously mentioned, we can extract the effective potential

$ V(r) $ between the nucleus and single hyperon from SHF calculations, in particular from the nucleon and hyperon density distributions. In this study, we selected the Skyrme force SLy5 for nucleon-nucleon interaction and the Nijmegen potential NSC97f for hyperon-nucleon interaction. The Nijmegen potential NSC97f was chosen because it can successfully describe the binding energy of single hyperon in hypernuclei and also effectively accounts for the binding energy of multiple hyperons in multi-hyperon hypernuclei [30]. The SLy5 interaction was selected for nucleon-nucleon interactions because of its good performance in describing nuclear structures [74, 75]. Additionally, once the hyperon-nucleon interaction is determined, the choice of nucleon-nucleon interaction has a insignificant impact on the binding energies of hyperons [24].The integral function (Eq. (8)) can be converted into an equivalent matrix equation involving the summation over a finite set of mesh points

$ k_i $ in the momentum space:$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \dfrac{\hbar^2k_i^2}{2\mu}\phi(k_j)\delta_{i,j}+\sum \limits_j V_l(k_i,k_j)\phi(k_j)k_j^2\omega_j=E\phi(k_i), \end{array} $

(10) where

$ \omega_j $ represents the weight of the j-th momentum mesh point. The complex Gaussian-Legendre mesh was adopted in our calculations. Moreover, our contours comprised line segments in the complex momentum space. Generally speaking, as long as the contour can enclose the targeted discrete eigenstates and the momentum cutoff$ k_{\rm max} $ is sufficiently large, the shape of the contour has no effect on the final calculation result.In addition, one can also find that the contour

$k{\rm e}^{-{\rm i}\theta}$ is exactly equivalent to complex scaling in the coordinate space:$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} U(\theta)f({r})=\exp({\rm{i}}\dfrac{3}{2}\theta)f({r}\exp({\rm{i}}\theta)). \end{array} $

(11) However, when excessively large complex scaling angles are employed in CSM, the computation becomes unstable. However, this issue does not exist for CMR. Therefore, CMR exhibits higher computational performance for broader resonant states.

In this study, we only addressed the resonance states of spherical hypernuclei through CMR. In the more general case of deformed potentials, coupling effects of higher excited energy levels could be crucial for analyzing deformed hypernuclei. Moreover, extending CMR to coupled-channel problems is also straightforward and convenient, enabling further discussion of the impact of deformation effects on hyperon emission.

-

The level density

$ \rho(\varepsilon) $ of the full Hamiltonian h is defined by:

where

$ \varepsilon_i $ are eigenvalues of h, and summation and integration are taken for discrete and continuous eigenvalues, respectively. This definition of the level density can also be expressed with the help of the Green's function:$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \rho(\varepsilon)= -\dfrac{1}{\pi} {\rm{Im}}\left\{{\rm{Tr}}\left[\dfrac{1}{\varepsilon+ {\rm i}\,0-h}\right]\right\}. \end{array} $

(13) When the Hamiltonian is described by the sum of an asymptotic term

$ h_0 $ and the short-range interaction V, namely$ h=h_0+V $ , CLD (denoted by$ \Delta(\varepsilon) $ ) for an energy ε is expressed using the density$ \rho(\varepsilon) $ obtained from the full Hamiltonian h and level density$ \rho_0(\varepsilon) $ of continuum states obtained from the asymptotic Hamiltonian$ h_0 $ as follows:$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Delta(\varepsilon)=\;&\rho(\varepsilon)-\rho_0(\varepsilon)\\=\;&-\dfrac{1}{\pi}{\rm{Im}}\left[{\rm{Tr}}\left\{\dfrac{1}{\varepsilon+{\rm i}\,0-h}-\dfrac{1}{\varepsilon+{\rm i}\,0-h_0}\right\}\right]. \end{aligned} $

(14) Additionally,

$ \Delta(\varepsilon) $ is well known to be related to the scattering S-matrix$ S(\varepsilon) $ as follows:$ \Delta(\varepsilon)=\dfrac{1}{2\pi}{\rm{Im}}\dfrac{\rm d}{{\rm d}\varepsilon}\ln\{\det S(\varepsilon)\}, $

(15) for a single channel system, the scattering S-matrix can be expressed as

$S(\varepsilon)={\rm e}^{2{\rm i}\delta(\varepsilon)}$ , where$ \delta(\varepsilon) $ is the scattering phase shift. In this case, we can obtain the simplified CLD and scattering phase shift as follows:$ \Delta(\varepsilon)=\dfrac{1}{\pi}\dfrac{{\rm d}\delta}{{\rm d}\varepsilon}, \quad \delta(\varepsilon)=\pi\int_{-\infty}^{\varepsilon}\Delta(\varepsilon'){\rm d}\varepsilon'. $

(16) -

If the energy spectrum is obtained through N momentum mesh points in the CMR, CMR-CLD can be expressed in the following form:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \Delta_N^{\rm CMR}(\varepsilon)=\;&\sum\limits_b^{N_B}\delta(\varepsilon-\varepsilon_b)+\dfrac{1}{\pi}\sum_r^{N_R^{\rm CMR}}\dfrac{\Gamma_r/2}{(\varepsilon-\varepsilon_r)^2+\Gamma_r^2/4}\\&+\dfrac{1}{\pi}\sum\limits_C^{N_C^{\rm CMR}=N-N_B-N_R^{\rm CMR}}\dfrac{\epsilon_C^I}{(\varepsilon-\epsilon_C^R)^2+{\epsilon_C^I}^2}\\&-\dfrac{1}{\pi}\sum\limits_C^{N}\dfrac{\epsilon_C^{0I}}{(\varepsilon-\epsilon_C^{0R})^2+{\epsilon_C^{0I}}^2}, \end{aligned} $

(17) where

$ \varepsilon_b $ ,$\varepsilon_r-{\rm i}\Gamma_r/2$ and$\epsilon^R-{\rm i}\epsilon^I$ are eigenvalues of the full Hamiltonian$ h=T+V $ and$\epsilon^{0R}-{\rm i}\epsilon^{0I}$ are eigenvalues of asymptotic Hamiltonian$ h_0=T $ .$ N_B $ represents the number of the bound state and$N_{R}^{\rm CMR}$ represents the number of the resonant state.According to Eq. (16), the phase shift within the N complex momentum mesh points in the CMR can be expressed as follows:

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \delta_N^{\rm CMR}(\varepsilon)=\;&\pi\int_{-\infty}^{\varepsilon}\Delta_N^{\rm CMR}(\varepsilon)\\& =N_B\pi+\sum\limits_{r=1}^{N_R^{\rm CMR}}\int_0^{\varepsilon} {\rm d}\varepsilon\dfrac{\Gamma_r/2}{(\varepsilon-\varepsilon_r)^2+\Gamma_r^2/4}\\&+\int_0^{\varepsilon} {\rm d}\varepsilon[\sum\limits_{C=1}^{N_C^{\rm CMR}}\dfrac{\epsilon_C^I}{(\varepsilon-\epsilon_C^R)^2+{\epsilon_C^I}^2}-\sum\limits_{C=1}^{N}\dfrac{\epsilon_C^{0I}}{(\varepsilon-\epsilon_C^{0R})^2+{\epsilon_C^{0I}}^2}]\\&=N_B\pi+\delta_R(\varepsilon)+\delta_C(\varepsilon), \end{aligned} $

(18) where the resonance and non-resonance phase shifts are expressed as follows:

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} \delta_R(\varepsilon)=\sum\limits_{r=1}^{N_R^{\rm CMR}}\delta_r(\varepsilon), \quad \delta_C(\varepsilon)=\sum\limits_{c=1}^{N_C^{\rm CMR}}\delta_c(\varepsilon)-\sum\limits_{c=1}^{N}\delta_c^0(\varepsilon). \end{array} $

(19) -

Using CLD, the scattering phase shifts can be conveniently obtained from the energy spectrum. To extract information such as scattering length, effective range, and resonance energies from the phase shifts, we set the ERE to expand the phase shift

$ \delta_l $ through a power series in momentum k:$ \begin{aligned}[b] & C_l^2(\eta) k^{2l+1}\left[\cot(\delta_l)+\dfrac{2\eta H(\eta)}{C_0^2(\eta)}\right]\\=\;&-\dfrac{1}{a_l}+\dfrac{r_l k^2}{2}+P_l r_l^3k^4+{O}(k^6), \end{aligned} $

(20) where

$ a_l $ is the scattering length,$ r_l $ is the effective range, and$ P_l $ is the shape parameter of partial wave l. In this expression,$ C_l^2(\eta) $ ,$ C_0^2(\eta) $ , and$ H(\eta) $ are expressed as follows:$ \begin{aligned}[b] C_l^2(\eta)=\;&C_{l-1}^2(\eta)(1+\dfrac{\eta^2}{l^2}), \ C_0^2(\eta)=\frac{2\pi\eta}{{\rm e}^{2\pi\eta}-1},\\ H(\eta)=\;&\sum\limits_{s=1}^{\infty}\frac{\eta^2}{s(s^2+\eta^2)}-\ln(\eta)-\gamma \\=\;&-\dfrac{{\rm i}\,\pi}{{\rm e}^{2\pi\eta}-1}+\Psi({\rm i}\,\eta)+\dfrac{1}{2{\rm i}\,\eta}-\ln({\rm i}\,\eta) , \end{aligned} $

(21) where

$\eta=\dfrac{Z_1Z_2{\rm e}^2\mu}{\hbar^2k}$ ,$ \gamma=0.5772156649\cdots $ is the Euler's constant, and$ \Psi(z) $ is the logarithmic derivative of the Γ function (Ψ function or digamma).In the case of neutral particle scattering, the effective range expansion reads

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} & k^{2l+1}\cot(\delta_l)=-\dfrac{1}{a_l}+\dfrac{r_l k^2}{2}+P_l r_l^3k^4+{O}(k^6). \end{array} $

(22) According to the form of the on-shell elements of the T-matrix,

$T(k,k)=\dfrac{(4\pi)^2}{2\mu k}\dfrac{1}{\cot(\delta_l(k))-{\rm{i}}}$ , one can find that the resonance is the pole of the T-matrix and thus the phase shift at the complex momentum$ k_{\rm res}=\dfrac{\sqrt{2\mu E_{\rm res}}}{\hbar} $ of the resonant state satisfies the condition$\cot(\delta_l(k_{\rm res}))={\rm{i}}$ . Therefore, through effective range expansion, the parametrization of the phase shift at$k_{\rm res}$ satisfies the following equation:$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} &-\dfrac{1}{a_l}+\dfrac{r_l k^2}{2}+P_l r_l^3k^4+{O}(k^6)=C_l^2(\eta) k^{2l+1}\left[{\rm i} +\dfrac{2\eta H(\eta)}{C_0^2(\eta)}\right], \end{array} $

(23) and for neutral particle scattering, Eq. (23) becomes

$ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} &-\dfrac{1}{a_l}+\dfrac{r_l k^2}{2}+P_l r_l^3k^4+{O}(k^6)= ik^{2l+1}. \end{array} $

(24) -

Owing to the considerably shorter lifetimes observed in hypernuclei compared to those of conventional atomic nuclei, it was assumed in previous studies on hypernuclear resonant states that their cores exist in deeply bound states. Accordingly, stable nuclei such as

$ {}^{16} $ O,$ {}^{40} $ Ca,$ {}^{48} $ Ca, and$ {}^{56} $ Ni were designated as core nuclei for this purpose. First, from calculations based on the SHF method, the effective interaction between the hyperon and nuclear core can be extracted as$ V(r) $ . In practical computations, only the effective potential in a finite region$ r<r_{\rm max} $ can be obtained using the SHF method. To provide potential in the entire coordinate space, we employed a Woods-Saxon form$ \dfrac{V_0}{1+{\rm e}^{\frac{r-R}{a}}} $ to fit$ V(r) $ and the analytical potential beyond$r_{\rm max}$ in Eq. (9). The parameters in Woods-Saxon potentials are listed in Table 1.Hypernuclei a/fm R/fm $ V_0 $ /MeV

$ {}^{17}_{\Lambda} $ O

0.4264 3.103 −28.75 $ {}^{40}_{\Lambda} $ Ca

0.4383 4.128 −30.46 $ {}^{48}_{\Lambda} $ Ca

0.4630 4.388 −30.46 $ {}^{56}_{\Lambda} $ Ni

0.4438 4.647 −30.18 Table 1. Parameters of the Woods-Saxon potentials. These parameters were derived by fitting the effective interaction obtained from the SHF method with the Woods-Saxon potential. In practical calculations, these parameters are used in the region where

$r > r_{\rm max}$ .The effective hyperon-nucleus interactions

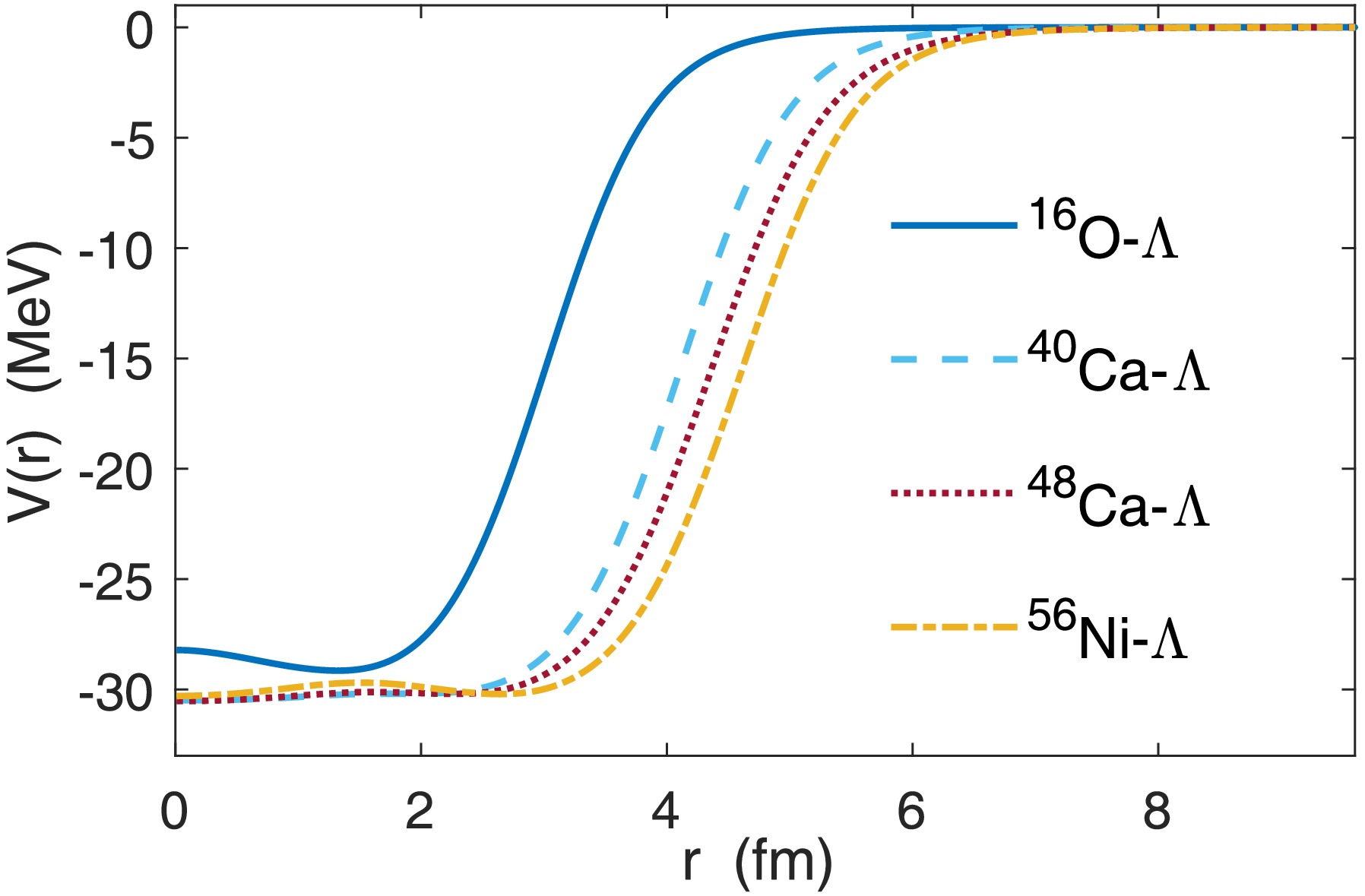

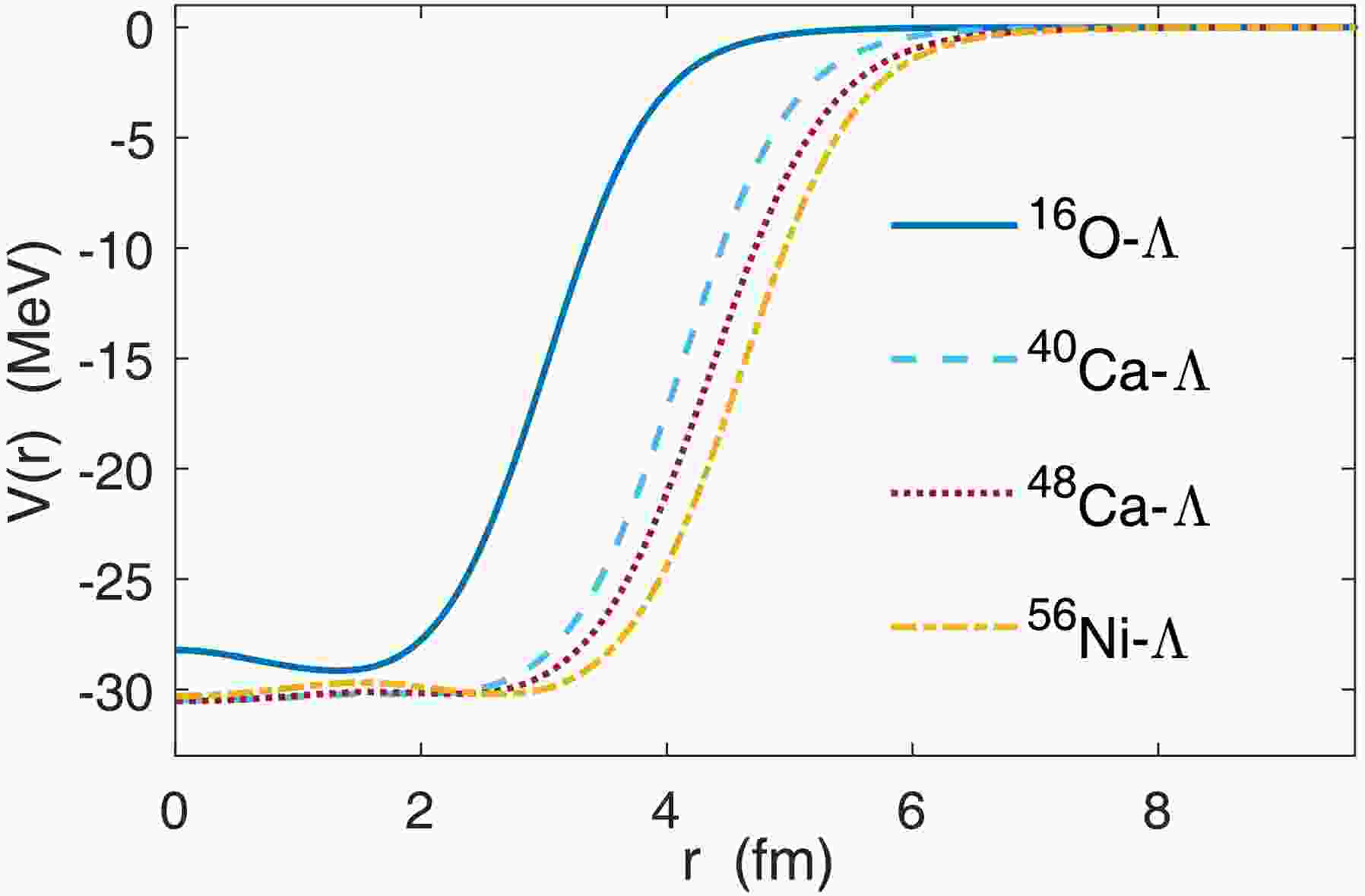

$ V(r) $ for$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O,$ {}^{41}_{\Lambda} $ Ca,$ {}^{49}_{\Lambda} $ Ca, and$ {}^{57}_\Lambda $ Ni are plotted in Fig. 1. For these nearly spherical nuclei, the deformation obtained from SHF calculations is very small and can be neglected. Hence, we only need to consider the single-channel scattering process. However, if the deformation is significant and cannot be ignored, the deformed potentials and corresponding coupled-channel equations must be considered. It should also be noted that in the calculations presented in this paper, we assumed that the energy level splitting induced by spin-orbit coupling is relatively small compared to the energy levels themselves. Thus, we neglected the influence of the spin-orbit coupling potential. However, if a more detailed discussion of the level splitting is required, a phenomenological spin-orbit coupling potential based on$ V(r) $ can be derived within the current framework.

Figure 1. (color online) Effective potential between the hyperon and nuclear core extracted from the SHF method. Solid, dashed, dotted, and dash-dot lines represent the effective potential

$ V(r) $ for$ {}^{17}_{\Lambda} $ O,$ {}^{41}_{\Lambda} $ Ca,$ {}^{49}_{\Lambda} $ Ca, and$ {}^{57}_{\Lambda} $ Ni, respectively.In the following, we illustrate the results of CMR-CLD and effective range expansion by taking

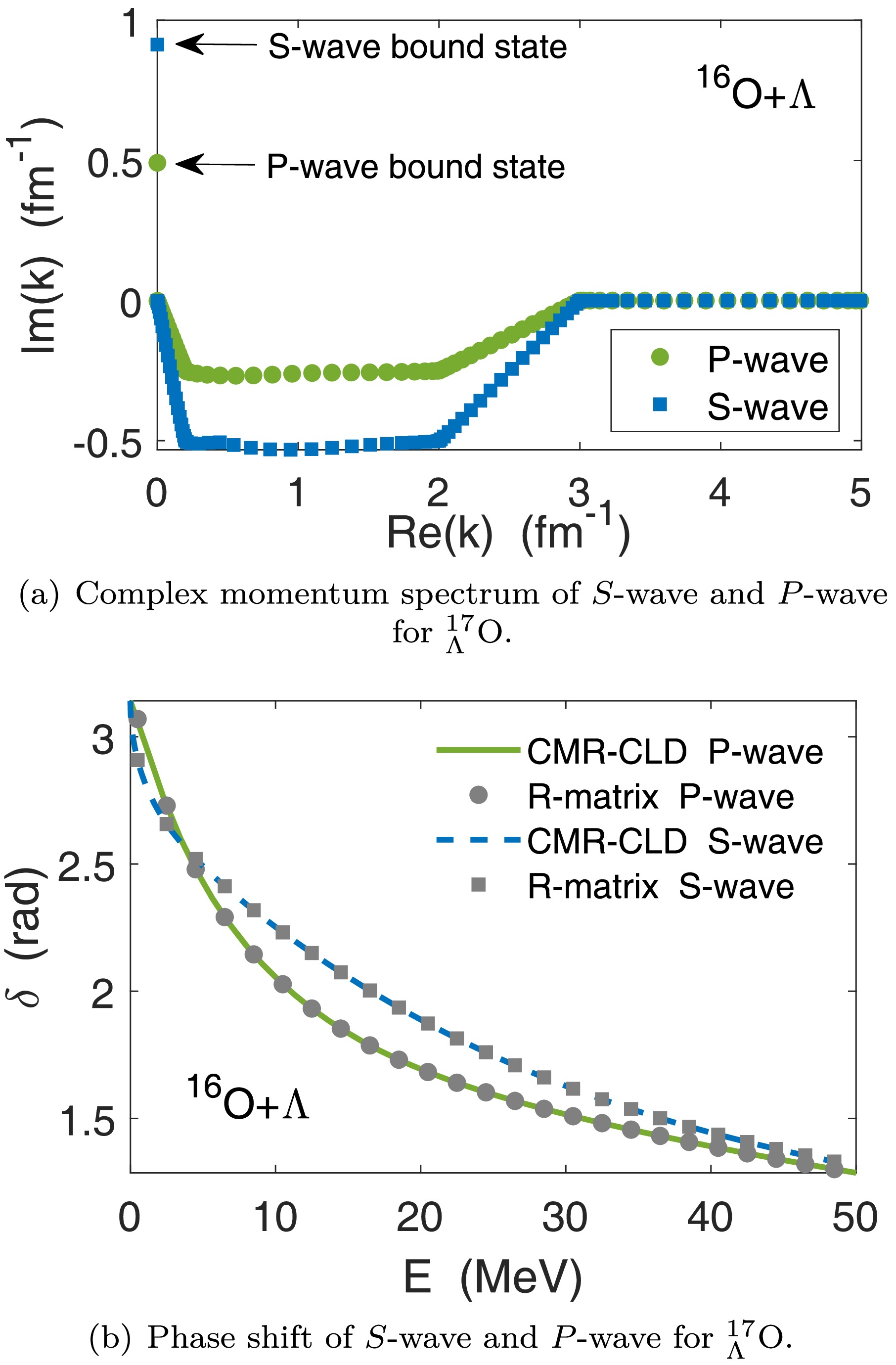

$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O as an example. When solving the Schrödinger equation in the momentum space, the truncation of momentum is$ k_{\rm max}=5 $ fm$ {}^{-1} $ , which is large enough to guarantee the stabilization of the numerical solutions. For CMR-CLD, as long as the contour encompasses discrete eigenvalues, these discrete eigenvalues are independent of the choice of the contour. Furthermore, once the discrete eigenvalues can be accurately solved, the phase shifts obtained through CLD do not depend on the contour shape.Figure 2 shows the complex momentum spectra and phase shifts obtained through CMR-CLD for

$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O with orbital angular momentum$ l=0 $ and$ l=1 $ . Both states with$ l=0 $ and$ l=1 $ are bound states whose positions are marked on the positive imaginary axis in panel (a). Panel (b) shows the scattering phase shifts obtained with both CMR-CLD and the conventional R-matrix method, where circular and square markers represent the P-wave and S-wave phase shifts obtained from the R-matrix method, and the solid and dashed lines correspond to the P-wave and S-wave phase shifts obtained from CMR-CLD. In the R-matrix calculation of scattering phase shifts, we adopted the conventional Lagrange functions over the interval$ (0,a) $ , with the channel radius a set to approximately 20 fm (large enough to neglect the short-range nuclear interaction) and the number of grid points set to approximately 50. The same parameters were used in the calculation of resonant states.

Figure 2. (color online) (a) Complex momentum spectra of

$ {}^{17}_{\Lambda} $ O obtained from CMR. The square and circle markers correspond to the results for S-wave and P-wave, respectively. Two bound states are marked on the positive imaginary axis. (b) Phase shifts of$ {}^{17}_{\Lambda} $ O for S-wave and P-wave. The square and circle markers represent the phase shifts obtained from the R-matrix method for S-wave and P-wave, respectively. The dashed and solid lines represent the phase shifts obtained from CMR-CLD for S-wave and P-wave, respectively.When considering a higher angular momentum, the

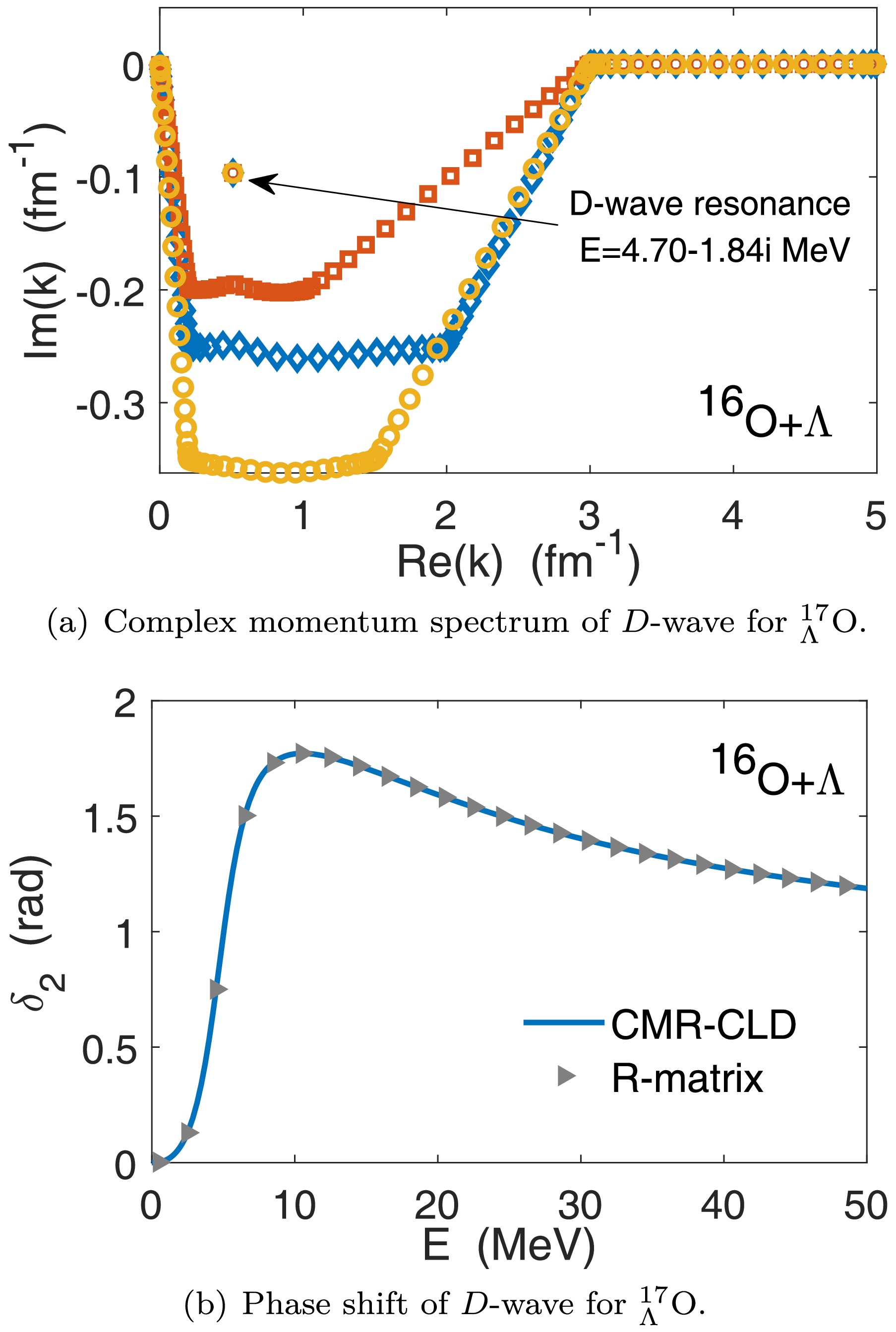

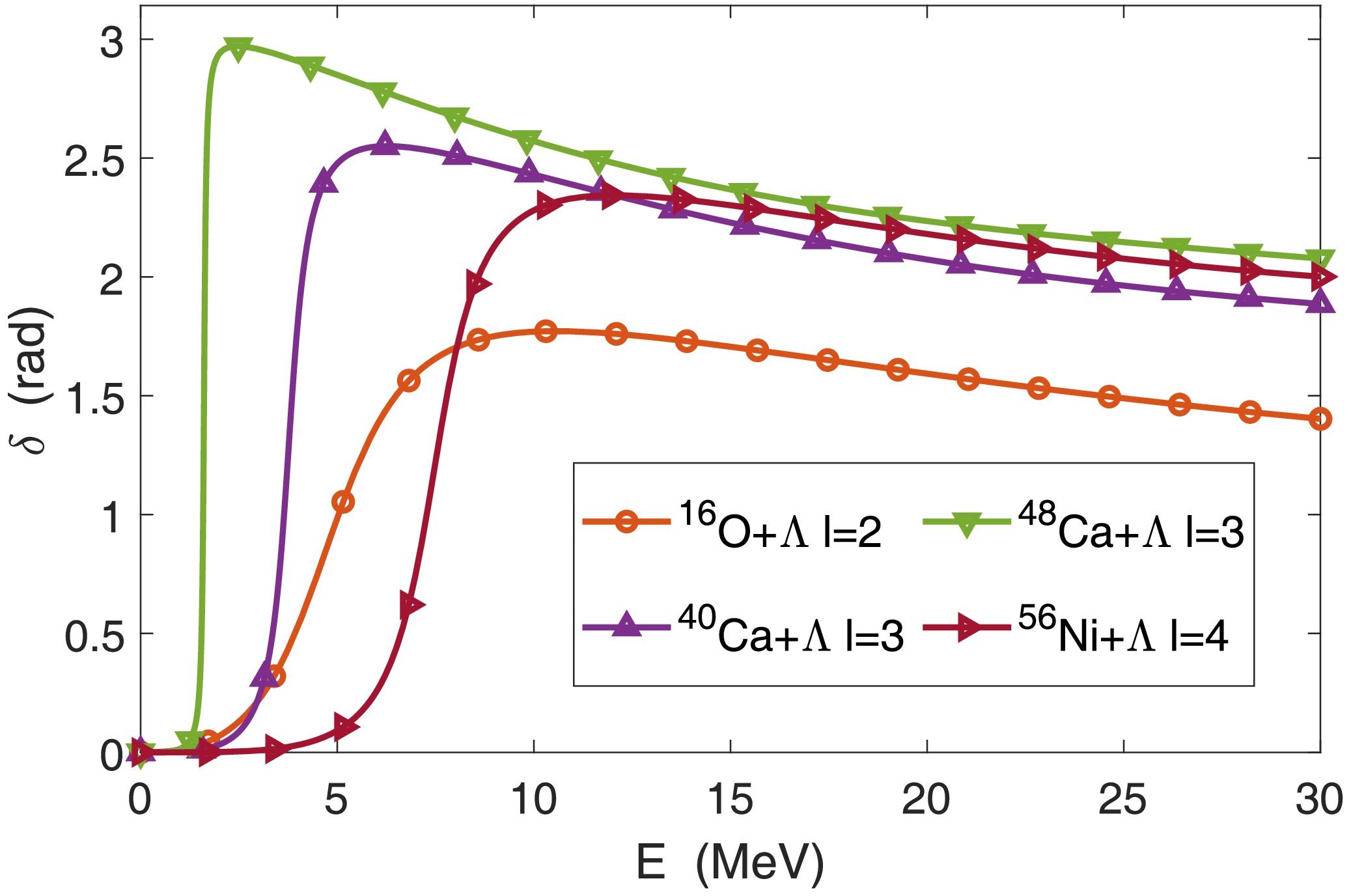

$ l=2 $ state becomes a resonance due to the stronger repulsive centrifugal potential. As shown in Fig. 3(a), a resonance appears in the fourth quadrant of the complex momentum space. The square, diamond, and circular markers in panel (a) represent the complex momentum spectra obtained using three different contour shapes. It can be observed that the position of the resonant state remains almost unchanged regardless of the contour shape. Fig. 3(b) shows the phase shifts of$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O for D-wave scattering. The triangle markers and solid line represent the results obtained from CMR-CLD and R-matrix, respectively. Similar calculations were performed for other systems. We show the phase shifts corresponding to the first resonant state of$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O,$ {}^{41}_{\Lambda} $ Ca,$ {}^{49}_{\Lambda} $ Ca, and$ {}^{57}_\Lambda $ Ni in Fig. 4. The solid lines represent results obtained using CMR-CLD, while the markers denote results obtained with the R-matrix method.

Figure 3. (color online) (a) Complex momentum spectra of

$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O obtained from CMR. The square, circle, and rhombus markers correspond to three different contours. The D-wave resonant state and its eigenenergy are marked in this panel. (b) Phase shifts of$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O for D-wave. The triangle markers represent the phase shifts obtained from R-matrix and the solid line represents the results obtained from CMR-CLD.

Figure 4. (color online) Scattering phase shifts at the appearance of the first resonant state. Solid lines represent the calculations from CMR-CLD, while circle, square, diamond, upward triangle, downward triangle, and right triangle markers correspond to the results from the R-matrix method for

$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O,$ {}^{41}_{\Lambda} $ Ca,$ {}^{49}_{\Lambda} $ Ca, and$ {}^{57}_\Lambda $ Ni, respectively.After obtaining the phase shifts through CMR-CLD, we also extracted physical quantities such as the scattering length and complex resonant energy by applying ERE. For the D-wave scattering of

$ {}^{17}_\Lambda $ O, these extracted physical quantities are listed in Table 2. For other systems, the calculations are similar and the corresponding results are also listed in Table 2.Nuclear core l $a_l^{\rm CMR-CLD+ERE}$ /fm

$ {}^{2l+1} $

$a_l^{R-{\rm matrix}}$ /fm

$ {}^{2l+1} $

$E_{\rm res}^{R-{\rm matrix}}$ /MeV

$E_{\rm res}^{\rm CMR-CLD+ERE}$ /MeV

$E_{\rm res}^{\rm CMR}$ /MeV

$ {}^{16} $ O

2 −16.50 −16.49 4.70-1.84i 4.70-1.84i 4.70-1.84i $ {}^{40} $ Ca

3 −53.02 −53.03 3.76-0.387i 3.76-0.387i 3.76-0.387i $ {}^{48} $ Ca

3 −181.0 −180.9 1.61-0.0408i 1.61-0.0406i 1.61-0.0408i $ {}^{56} $ Ni

4 −30.93 −30.98 7.46-0.951i 7.46-0.954i 7.46-0.951i Table 2. Complex resonant energy

$E_{\rm res}$ and scattering length$ a_l $ obtained from CMR-CLD and R-matrix. Here, the angular momentum l supports the first resonant state;$a_{l}^{\rm CMR-CLD+ERE}$ and$E_{\rm res}^{\rm CMR-CLD+ERE}$ denote the scattering length and resonant energy obtained from CMR-CLD plus effective range expansion, respectively;$E_{\rm res}^{\rm CMR}$ is the result obtained from pure CMR. Here, "pure" refers to extracting resonant energies solely from the momentum spectrum obtained from CMR. To ensure reliable resonance extraction, we carefully selected an appropriate integral contour.$a_{l}^{R-{\rm matrix}}$ and$E_{\rm res}^{R-{\rm matrix}}$ denote the scattering length and resonant energy obtained from the R-matrix method, respectively. In the R-matrix calculations, the channel radius was set to be approximately 20 fm and approximately 50 Gaussian-Legendre grid points were used.The first column represents the nuclear core, the second column denotes the angular momentum l which supports the first resonant state, the third column indicates the scattering length

$ a_l $ obtained from CMR-CLD with effective range expansion, the fourth column shows the scattering length obtained from the R-matrix method, the fifth column shows the complex resonant energy$E_{\rm res}$ obtained from the R-matrix method, the sixth column shows$ E_{\rm res} $ obtained from CMR-CLD plus effective range expansion, and the last column represents$ E_{\rm res} $ obtained from CMR.Generally speaking, the positive or negative phase shift at a certain scattering energy indicates whether the interaction is attractive or repulsive. Owing to the connection between phase shift

$ \delta_l(k) $ and scattering length$ a_l $ , namely$ \lim\limits_{k\rightarrow 0}\dfrac{k^{2l+1}}{\tan(\delta_l(k))}=-\dfrac{1}{a_l} $ , a negative scattering length corresponds to a positive scattering phase shift near zero energy, which indicates an attractive effect in this energy region, while a positive scattering length reflects a repulsive effect. Moreover, qualitatively speaking, the larger (in absolute value) the scattering length is, the stronger the attractive (or repulsive) effect near zero energy becomes. This can also be partially concluded from Table 2: the larger absolute values of the scattering length correspond to smaller decay widths, which indicates stronger attractive effect between the Λ hyperon and nuclear core. However, it should be noted that such comparison should be based on the condition of equal angular momentum. Thus, the magnitude of scattering lengths cannot be directly compared for different angular momentum cases.Table 2 clearly shows that the values of complex resonant energy obtained from CMR closely matches those obtained from the conventional R-matrix method. Additionally, the scattering length and complex resonant energy extracted through effective range expansion also exhibit good agreement with results obtained from the R-matrix method. These numerical results validate the reliability and accuracy of the CMR-CLD method in dealing with resonance problems for single hyperon hypernuclei in the case of spherical potential.

Overall, we conclude from these numerical results that for the single Λ hypernuclei considered, the decay width is approximately in the MeV range, which is much larger than the decay width derived from the weak decay lifetime of hypernucleus. Therefore, this indicates that the time involved in the emission process within the hypernucleus is much shorter than its weak decay lifetime and also much shorter than the half-life of a free Λ hyperon. These results suggest that even if the weak decay lifetime of the hypernucleus is notably short, the emission process of the hyperon should also be considered and investigated.

-

We combined the SHF method with complex momentum representation to investigate the resonances of single hyperon hypernuclear and obtain the complex resonant energy by solving the single channel Schrödinger equation in the complex momentum space. CMR offers the advantage of employing bound state techniques to address resonances. Moreover, when considering deformed potentials, CMR can be easily extended to coupled-channel sectors. The influence of deformation effects on hyperon emission will be further discussed in the future. In the present study, by properly selecting the momentum cutoff and contour for the integral, the resonance energies obtained from CMR were highly consistent with the results from the R-matrix method. In addition, using the CLD method, the phase shifts were calculated using the energy spectrum obtained from CMR. The scattering phase shifts from CMR-CLD were in good agreement with those from the R-matrix method. Additionally, by applying effective range expansion, we extracted a reliable value of the scattering length, from which we obtained information about the strength of the attractive interaction between the hyperon and nuclear core during the scattering process.

Our study of the spherical nuclear system with a single hyperon demonstrates the high reliability of the CMR-CLD method, which establishes the foundation for future investigations using CMR-CLD to study resonant states in deformed single-hyperon and multi-hyperon hypernuclei.

Resonance of hypernuclei with complex momentum representation

- Received Date: 2024-09-03

- Available Online: 2025-04-15

Abstract: By combining the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock method with complex momentum representation (CMR), the resonant states of

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: