-

In this study, we use a statistical hadronization model to describe hadron production in heavy-ion collisions in the few-GeV energy regime [1−3]. This approach effectively describes the transverse momentum and rapidity spectra of protons and pions. Furthermore, it accurately reproduces the experimentally measured deuteron yield [4], provided that, among the two options, the freeze-out corresponding to the higher temperature is selected. We consider a version of the model that incorporates spheroidal hydrodynamic expansion [2], which is more realistic than the one that assumes spherical symmetry. The latter was used in the original blast-wave model by Siemens and Rasmussen [5]; see also Ref. [6]. It is important to note that our assumptions differ from the commonly used boost-invariant blast-wave models applied at ultrarelativistic energies [7], which are not suitable at lower beam energies.

Our analysis is based on data collected by the HADES Collaboration for Au-Au collisions at a beam energy

$ \sqrt{s_{NN}}= $ 2.4 GeV and a centrality class of 10% [8−10]. Fits to the particle abundances performed by us and other groups [11] suggest two distinct sets of possible freeze-out thermodynamic parameters. In particular, they correspond to two different freeze-out temperatures: T = 49.6 MeV and T = 70.3 MeV. Since the analysis of deuteron production favors the higher temperature scenario [4], we adopt T = 70.3 MeV throughout this study. In this case, the system size R is relatively small, approximately 6 fm. As a result, the probability of nucleus formation via nucleon triplet is relatively large (compared to the low-temperature case where$ R \approx 16 $ fm). The thermodynamic parameters used in our calculations, i.e., temperature, baryon chemical potential, and isospin chemical potential, are listed in Table 1. The thermodynamic parameters related to strangeness production are not shown, as they are irrelevant to the present analysis.T/MeV $ \mu_{{\rm{B}}} $ /MeV

$ \mu_{{\rm{I}}_3} $ /MeV

R/fm H/MeV δ $ v_R $

$ \gamma_R $

70.3 876 −21.5 6.06 22.5 0.4 0.60 1.25 Table 1. Thermodynamic parameters (temperature T, baryon chemical potential

$ \mu_{{\rm{B}}} $ , isospin chemical potential$ \mu_{{\rm{I}}_3} $ ), system radius R, Hubble expansion parameter H, longitudinal eccentricity δ, radial flow$ v_R $ , and Lorentz gamma factor at the system's boundary ($ r=R $ )$ \gamma_R $ , extracted from experimental data.In the collisions of gold nuclei considered, one detects on average per event about 28.7 nuclei of 2H, 8.7 nuclei of 3H, and 4.6 nuclei of 3He [8, 9].

1 Hence, about 46.5 protons are found in the bound states. The remaining average number of directly produced protons is 77.6. In the framework defined in Refs. [1, 2] we assume that all protons eventually detected in bound states and those measured as free particles originally form a thermal system. Thus, while comparing the predictions of our model with the data, the final results for the proton spectra are rescaled by the factor 77.6/(77.6+46.5). This implicitly assumes the existence of a certain physical mechanism that combines the remaining protons with neutrons into the light nuclei mentioned above. In the present work, we assume that this process can be interpreted as coalescence and use the standard expressions of the coalescence framework (see, for example, Refs. [12, 13]) to predict the light nuclei spectra. Continuing the approach from Ref. [4], we do not use Gaussian ad hoc parametrizations of the thermal source but rather consider initial particle production as independent thermal production within a sphere of the radius R (which is consistent with thermal model assumptions adopted in Refs. [1, 2]). Our present work does not include contributions from decaying resonances. We have verified using THERMINATOR [14, 15] that for the low-temperature case they are negligible, while for the high-temperature case only the Delta resonance plays a noticeable, though very small, role.The topic of producing light nuclei has recently attracted considerable interest (see, for example, Refs. [16−28]). In relativistic heavy-ion collisions, the production of such systems is well reproduced by both the thermal approach and the coalescence model. These two approaches are usually treated as exclusive alternatives (for a short and critical review of this issue, see Ref. [29]). In this study, we present a scenario for lower energies where the initial thermal production of particles is combined with a subsequent coalescence mechanism in a consistent way, showing that the two pictures may coexist and supplement each other.

The remainder of this paper has the following structure. In Sec. II, we introduce the coalescence model and discuss the nuclei formation rate. In Sec. III, the freeze-out model is defined. The spheroidal form of expansion is discussed in Sec. IV, where we introduce a compact description of the distribution functions with given symmetries, which becomes very useful for implementing the coalescence model. Our main numerical results are presented and discussed in Sec. V. We conclude the paper in Sec. VI. Throughout the paper, we use natural units:

$ c=\hbar=k_B=1 $ . The metric tensor has the signature$ (+1,-1,-1,-1) $ . -

In the coalescence model for light nuclei production, the particle spectrum is obtained as a product of proton and neutron spectra taken at a fraction of the nucleus momentum [30, 31]. Specifically, with the proton and neutron three-momentum distributions defined by

$ \begin{aligned} F_{{\rm{p}}}({\boldsymbol{p}}) = \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{p}}}}{ {\rm{d}}^3 p}, \quad F_{{\rm{n}}}({\boldsymbol{p}}) = \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{n}}}}{ {\rm{d}}^3 p}, \end{aligned} $

(1) the three-momentum distribution of a nucleus X with a mass number A and an atomic number Z is the product

$ \begin{aligned} \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{X}}}}{ {\rm{d}}^3 p_{{\rm{X}}}} = A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}} \left(\, F_{{\rm{p}}} \left(\frac{{\boldsymbol{p}}_{{\rm{X}}}}{A} \right)\right)^Z \left( F_{{\rm{n}}} \left(\frac{{\boldsymbol{p}}_{{\rm{X}}}}{A} \right)\right)^{A-Z}, \end{aligned} $

(2) where

$ A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}} $ is the particle formation rate coefficient discussed in more detail below, and the subscripts p and n refer to protons and neutrons, respectively.Equation (2) assumes the additivity of the three-momenta of the nuclei that form the considered nucleus,

$ {\boldsymbol{p}}_{{\rm{X}}} = A {\boldsymbol{p}} $ . Classically, this leads to a small violation of energy conservation: for example, owing to the finite nucleus binding energy,$ m_{\rm \,^3 He} = 2809 $ MeV, while$ m_{{\rm{p}}}+2m_{{\rm{n}}} = (938+2\times940) $ MeV = 2818 MeV. This and other related problems connected with the conservation laws in the coalescence model are usually circumvented with reference to the quantum nature of the real coalescence process, which introduces the natural uncertainty of the energies and momenta of interacting particles [12]. In any case, small differences due to the binding energy and the inequality of$ m_{{\rm{p}}} $ and$ m_{{\rm{n}}} $ do not affect our present analysis. Therefore, in the following, we use the approximation$ m_{{\rm{p}}} \approx m_{{\rm{n}}} \approx m $ , where m is the mean nucleon mass, and$ m_{{\rm{X}}} \approx Am $ . Hence, while switching from the variable$ {\boldsymbol{p}}_{{\rm{X}}} $ to the particle transverse momentum$ p_{\perp{\rm{X}}} $ and rapidity$ y_{{\rm{X}}} $ in Eq. (2), we use the simple rules$ \begin{aligned} p_\perp = \frac{p_{\perp{\rm{X}}}}{A}, \quad y = y_{{\rm{X}}}. \end{aligned} $

(3) As in both theory and experiment, one usually deals with invariant momentum distributions,

$ E \, {\rm{d}} N/( {\rm{d}}^3 p) $ , rather than distributions of forms presented in Eq. (1). It is convenient to recall that, for systems with cylindrical symmetry (with respect to the beam axis z) considered in this study, we have$ \begin{aligned} \frac{ {\rm{d}} N}{ {\rm{d}}^3 p} = \frac{ {\rm{d}} N}{2\pi\, E\, {\rm{d}} y\, p_\perp {\rm{d}} p_\perp} = \frac{ {\rm{d}} N}{2\pi E\, {\rm{d}} y\, m_\perp {\rm{d}} m_\perp}, \end{aligned} $

(4) where E is the on-mass-shell energy of a particle,

$ E=\sqrt{m^2+{\boldsymbol{p}}^2} $ , and$ m_\perp $ is its transverse mass,$ m_\perp=\sqrt{m^2+p_\perp^2} $ . Therefore, from Eq. (2), we obtain$ \begin{aligned}[b] \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{X}}}}{E_{{\rm{X}}}\, {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\perp{\rm{X}}} {\rm{d}} m_{\perp{\rm{X}}}} =\;& \frac{A_{{\rm{FR}}}^X}{\left(2\pi\right)^{A-1}} \left(\frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{p}}}}{E\, {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\perp} {\rm{d}} m_{\perp}}\right)^{Z}\\&\times\left( \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{n}}}}{E\, {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\perp} {\rm{d}} m_{\perp}}\right)^{A-Z}. \end{aligned} $

(5) Note that, since the momenta and energies of protons and neutrons are equal, the proton and neutron distributions differ only on account of the different thermodynamic parameters used in equilibrium distribution functions. Note also that, within our approximations

$ y_{{\rm{X}}}=y_{{\rm{p}}}=y_{{\rm{n}}}=y $ and at zero rapidity, Eq. (5) reduces to the formula$ \begin{aligned}[b] \left. \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{X}}}}{ {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\rm \perp X}^2 {\rm{d}} m_{\rm\perp X}} \right|_{y=0} =\;& \frac{A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}}}{\left(2\pi\right)^{A-1}}\left( \left.\frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{p}}}}{ {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\perp}^2 {\rm{d}} m_{\perp}} \right|_{y=0} \right)^Z\\&\times\left( \left.\frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{n}}}}{ {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\perp}^2 {\rm{d}} m_{\perp}} \right|_{y=0} \right)^{A-Z}. \end{aligned} $

(6) Previous works introduce two models that reproduce well the spectra of protons and neutrons [1, 2]. Here, we use one of these models to predict, based on Eq. (6), the spectra of 3H and 3He nuclei. For finite values of rapidity, Eq. (5) takes the form

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{X}}}}{ {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\rm \perp X}^2 {\rm{d}} m_{\rm \perp X}} =\;& \frac{A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}}}{\left(2\pi \cosh y\right)^{A-1}} \left( \frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{p}}}}{ {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\perp }^2 {\rm{d}} m_{\perp }}\right)^Z \\&\times\left(\frac{ {\rm{d}} N_{{\rm{n}}}}{ {\rm{d}} y\, m_{\perp }^2 {\rm{d}} m_{\perp }}\right)^{A-Z} . \end{aligned} $

(7) By integrating this equation over the transverse mass of the particle, we obtain the particle rapidity distribution.

-

A popular form of the coefficient

$ A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}} $ used in literature is [12]$ \begin{aligned}[b] A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}} =\;& \frac{2s_{{\rm{X}}}+1}{\left(2s+1\right)^A} (2\pi)^{3\left(A-1\right)} \int {\rm{d}}^3 r_1\dots {\rm{d}}^3 r_A \,D({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,\dots,{\boldsymbol{r}}_A) \, \\&\times\left| \phi_{{\rm{X}}}({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,\dots,{\boldsymbol{r}}_A)\right|^2, \end{aligned} $

(8) where the function

$ D({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,\dots,{\boldsymbol{r}}_A) $ represents the distribution of the space positions of neutrons and protons at freeze-out, normalized to unity;$ \phi_X({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,\dots,{\boldsymbol{r}}_A) $ is the light nucleus wave function; and s and$ s_{{\rm{X}}} $ stand for the nucleon spin and spin of X, respectively. Many studies on the coalescence model assume the Gaussian profile [32, 33]$ \begin{aligned} D({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,\dots,{\boldsymbol{r}}_A) = \left(4 \pi R_{{\rm{kin}}}^2 \right)^{-\frac{{3A}}{{2}}} \exp\left(- \frac{\sum_{i=1}^A {\boldsymbol{r}}_i^2 }{4 R_{{\rm{kin}}}^2} \right), \end{aligned} $

(9) where

$ R_{{\rm{kin}}} $ is the radius of the system at freeze-out. However, this formula may be considered inconsistent with the physical assumptions used in our model, where original particles are produced independently inside a sphere of radius R at a fixed laboratory time t [1, 2]. The expression (9) gives the root-mean-squared value$ r_{\rm rms} = \sqrt{6} R \approx 2.45 R $ , which implies hadron production far away from the original thermal system and its long formation time2 . Thus, as an alternative to the Gaussian distribution (9), we use the position distribution of particles that are produced independently within a sphere of radius R$ \begin{aligned} D({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,\dots,{\boldsymbol{r}}_A) =\left(\frac{3}{4\pi R^3}\right)^A \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-|{\boldsymbol{r}}_1|\right)\dots \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-|{\boldsymbol{r}}_A|\right), \end{aligned} $

(10) with the normalization condition

$ \begin{aligned} \int {\rm{d}}^3r_1 \, {\rm{d}}^3r_2 \, ... \, {\rm{d}}^3r_A D({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,\dots,{\boldsymbol{r}}_A) =1. \end{aligned} $

(11) In this study, since we are interested in the production of 3H and 3He nuclei, we consider the case

$ A = 3 $ and use the form$ \begin{aligned} D({\boldsymbol{r}}_1,{\boldsymbol{r}}_2,{\boldsymbol{r}}_3) =\left(\frac{3}{4\pi R^3}\right)^3 \, \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-|{\boldsymbol{r}}_1|\right) \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-|{\boldsymbol{r}}_2|\right) \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-|{\boldsymbol{r}}_3|\right). \end{aligned} $

(12) Here,

$ \theta_{{\rm{H}}}(x) $ is the Heaviside step function. In this case, it is convenient to introduce a set of normalized Jacobi coordinates$ \begin{aligned}[b] {\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} &= \frac{1}{3}\left({\boldsymbol{r}}_1+{\boldsymbol{r}}_2+{\boldsymbol{r}}_3\right), \\ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{12} &= {\boldsymbol{r}}_1-{\boldsymbol{r}}_2, \\ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{312} \equiv {{\boldsymbol{e}}} &= {\boldsymbol{r}}_3-\frac{1}{2}\left({\boldsymbol{r}}_1+{\boldsymbol{r}}_2\right). \end{aligned} $

(13) The coordinates

$ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} $ ,$ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{12} $ , and$ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{312} $ can be interpreted as the center of mass of the X system, the relative distance between two particles, and the distance between this pair's center of mass and a third particle, respectively. Changing to these variables, we write$ \begin{aligned}[b] D({\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}},{\boldsymbol{r}}_{12},{\boldsymbol{r}}_{312}) =\;& \left(\frac{3}{4\pi R^3}\right)^3 \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-\left|{\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} +\frac{{\boldsymbol{r}}_{12}}{2}-\frac{{\boldsymbol{r}}_{312}}{3}\right|\right) \\ & \times \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-\left|{\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}}-\frac{{\boldsymbol{r}}_{12}}{2}-\frac{{\boldsymbol{r}}_{312}}{3}\right|\right)\\&\times\theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-\left|{\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}}+\frac{2 \,{\boldsymbol{r}}_{312}}{3}\right|\right), \end{aligned} $

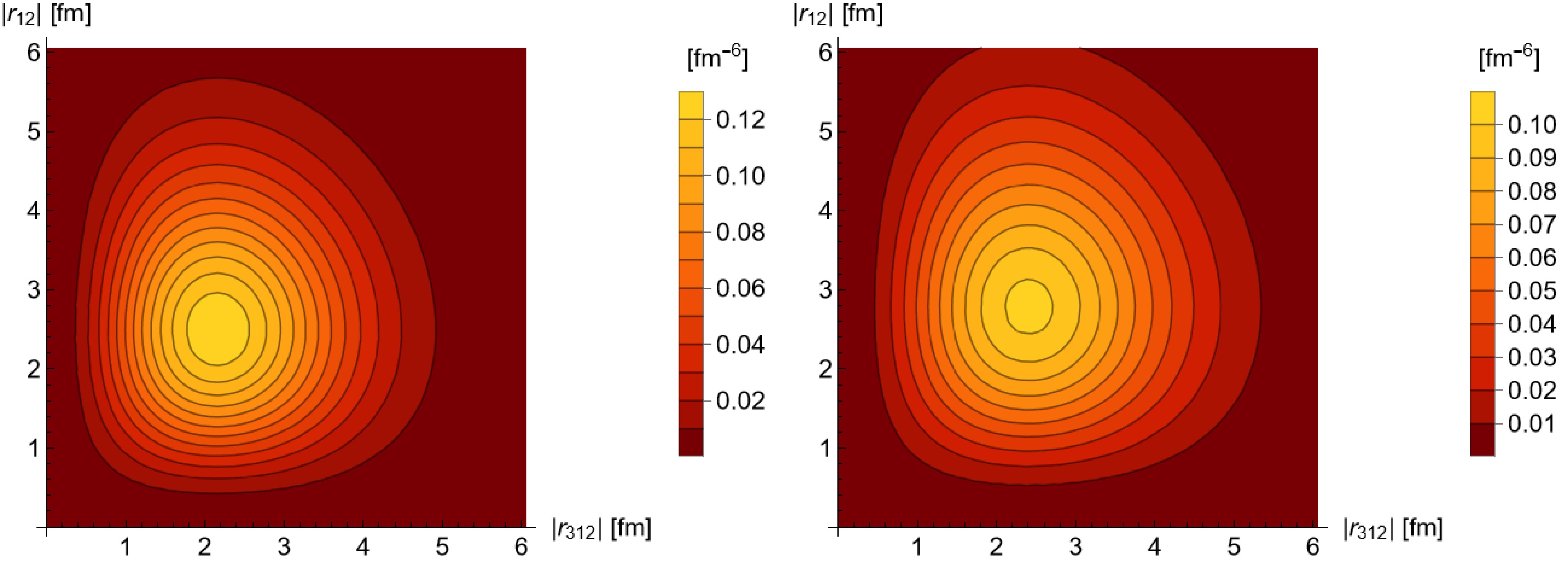

(14) For the wave functions of 3H and 3He, we use the Gaussian approximation in the same coordinates [19]

$ \begin{aligned} \left| \phi_X(r_{12},r_{312})\right|^2 = \left(3 \pi^2 R_{{\rm{X}}}^4 \right)^{-3/2} \exp\left(- \frac{r_{12}^2+\frac{4}{3} r_{312}^2}{ 2R_{{\rm{X}}} ^2} \right), \end{aligned} $

(15) where

$ R_{\rm \,^3 H} = 1.76\; $ fm and$ R_{\rm \,^3 He} = 1.96\; $ fm are the radii of 3H and 3He nuclei, respectively. The function$ \left| \phi_{{\rm{X}}}(r_{12},r_{312})\right|^2 $ is normalized to unity. In Ref. [4], it was argued that relativistic corrections can be neglected, and we continue this approach in this study. We note that the wave function's dependence on its arguments can be factorized, allowing us to write$ \begin{aligned}[b] A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}} =\;& \frac{{3\sqrt{3}}}{{4 R_{{\rm{X}}}^6 R^9}} \int {\rm{d}}^3r_{{\rm{cm}}} {\rm{d}}^3r_{12} \theta_{{\rm{H}}} \left(R-\left|{\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} + \frac{{{\boldsymbol{r}}_{12}}}{{2}}\right|\right)\\&\times \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-\left|{\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} - \frac{{{\boldsymbol{r}}_{12}}}{{2}}\right|\right) \exp \left( - \frac{{{\boldsymbol{r}}_{12}^2}}{{2 R_{{\rm{X}}}^2}} \right)\\ &\times \int {\rm{d}}^3r_{312} \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(R-\left|{\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} + {\boldsymbol{r}}_{312}\right|\right) \exp \left( - \frac{{2{\boldsymbol{r}}_{312}^2 }}{{3 R_{{\rm{X}}}^2}} \right). \end{aligned} $

(16) The inner integral is invariant under the rotation of

$ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} $ ; therefore, we can set$ \begin{aligned} {\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} = (0,0,r_{{\rm{cm}}}) \end{aligned} $

(17) and change the variables to

$ \begin{aligned}[b] \begin{split} {\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} + {\boldsymbol{r}}_{312} &= R {\boldsymbol{\rho}}_\delta \equiv R (x_\delta, y_\delta, z_\delta),\\ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{{\rm{cm}}} &= R {\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{c},\\ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{12} &= R {\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{12}, \end{split} \end{aligned} $

(18) which gives

$ \begin{aligned}[b] A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}} =\;& \frac{{3\sqrt{3}}}{{4 R_{{\rm{X}}}^6}} \int {\rm{d}}^3\rho_{c} {\rm{d}}^3\rho_{12} \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(1-\left|{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{c} + \frac{{{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{12}}}{{2}}\right|\right)\\&\times \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(1-\left|{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{c} - \frac{{{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{12}}}{{2}}\right|\right) \exp \left( - \frac{{{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{12}^2 R^2}}{{2 R_{{\rm{X}}}^2}} \right)\\ &\times \int {\rm{d}}^3\rho_{\delta} \theta_{{\rm{H}}}\left(1-|{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_\delta|\right ) \exp \\&\times\left[ - \frac{{2 R^2}}{{3 R_{{\rm{X}}}^2}} \left( x_\delta^2 + y_\delta^2 + \left(z_\delta - |{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_c|\right)^2\right)\right]. \end{aligned} $

(19) The inner integral is equal to

$ \begin{aligned}[b] I_1(\rho_c, \xi) =\;& \frac{{3 \pi}}{{8 \xi^4 \rho_c}} \Big[-3 \exp(-\phi^2) +3 \exp(-\chi^2) \\&+ \sqrt{6 \pi} \xi \rho_c (\rm{erf} \ \phi + \rm{erf} \ \chi) \Big], \end{aligned} $

(20) with

$ \begin{aligned} \xi = \frac{{R}}{{R_{{\rm{X}}}}}, \quad \phi = \sqrt{\frac{{2}}{{3}}} \xi (1- \rho_c), \quad \chi = \sqrt{\frac{{2}}{{3}}} \xi (1+ \rho_c). \end{aligned} $

(21) In the outer integral, we change the variables again to eliminate the step functions

$ {\boldsymbol{\rho}}_c + \frac{{{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{12}}}{{2}} = {\boldsymbol{a}},\quad {\boldsymbol{\rho}}_c - \frac{{{\boldsymbol{\rho}}_{12}}}{{2}} = {\boldsymbol{b}}, $

(22) $ \begin{aligned}[b] A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{{\rm{X}}} =\;& \frac{{3\sqrt{3}}}{{4 R_{{\rm{X}}}^6}} \underset{{\boldsymbol{a}}, {\boldsymbol{b}} \in B(1)}{\int} {\rm{d}}^3 a \, {\rm{d}}^3 b \exp \left[- \frac{{({\boldsymbol{b}} - {\boldsymbol{a}})^2 \xi^2}}{{2}} \right] \\&\times I_1 \left(\frac{{|{\boldsymbol{a}}+{\boldsymbol{b}}|}}{{2}},\xi \right), \end{aligned} $

(23) where

$ B(1) $ denotes a ball of radius 1 centered at the origin. The values of the formation rate coefficient for different freeze-out scenarios are listed in Table 2. The wave functions of 3H and 3He are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.Parameter Value/MeV6 $ A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{^{3}{\rm{H}}} $

$ 5.51\times 10^{11} $

$ A_{{\rm{FR}}}^{^{3}{\rm{He}}} $

$ 5.03\times 10^{11} $

Table 2. Values of the formation rate parameter

$ A_{{\rm{FR}}} $ for 3H and 3He nuclei.

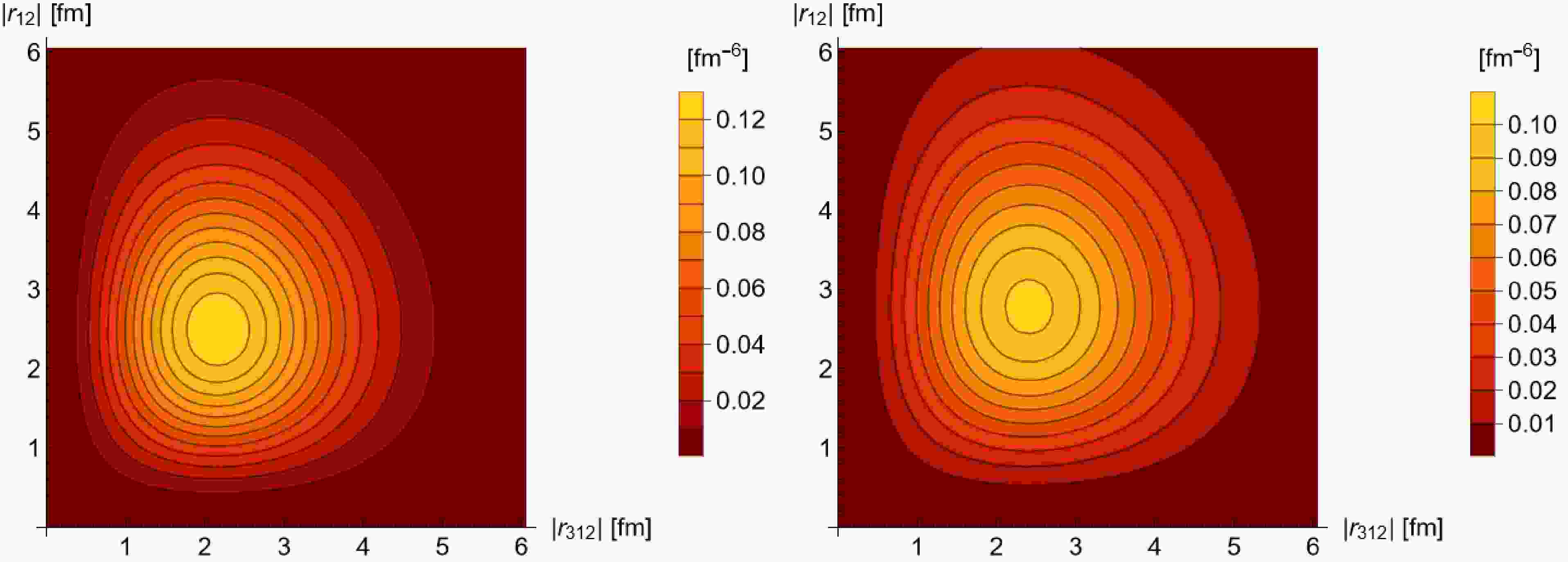

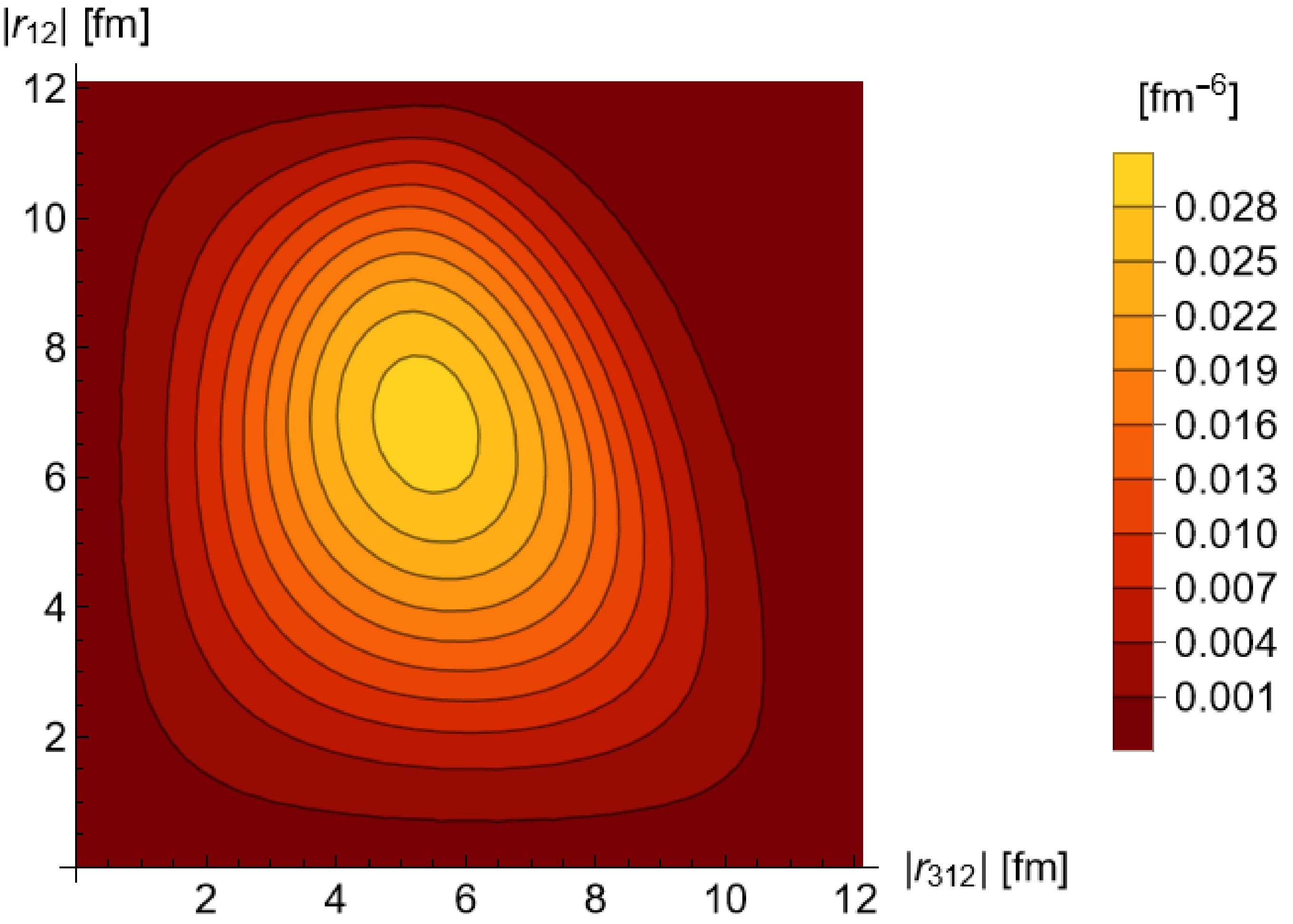

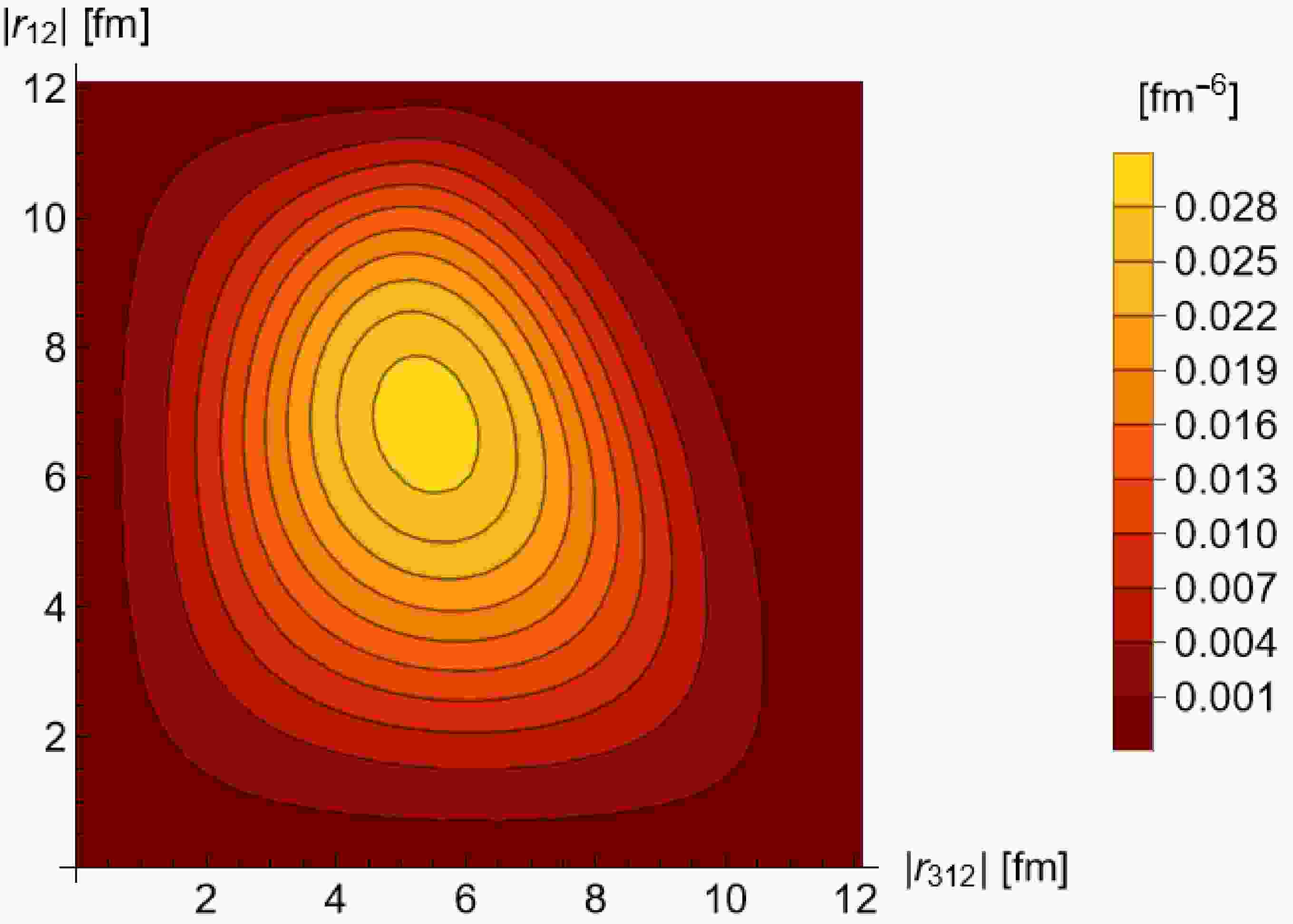

Figure 1. (color online) Nucleon space distribution integrated over the center of mass coordinate in terms of the moduli of the

$ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{12} $ and$ {\boldsymbol{r}}_{312} $ coordinates,$ D(r_{12},r_{312}) = \left(4\pi\right)^2 r_{12}^2 r_{312}^2 \int {\rm{d}} r^3_{{\rm{cm}}} $ $ D(r_{{\rm{cm}}},r_{12},r_{312}) $ . -

The freeze-out models specify the hydrodynamic conditions for particle production at the latest stages of the system's spacetime evolution. In the single-freeze-out scenario [34, 35] adopted here, the freeze-out stage is defined by a set of thermodynamic variables such as temperature T, baryon chemical potential

$ \mu_{{\rm{B}}} $ , and shape of the freeze-out hypersurface Σ. In addition, one defines the form of the hydrodynamic flow$ u^\mu(x) $ on Σ. -

The standard starting point for quantitative calculations is the Cooper-Frye formula [36], which describes the invariant momentum spectrum of particles

$ \begin{aligned} E \frac{ {\rm{d}} N}{ {\rm{d}}^3 p} = \int {\rm{d}}^3\Sigma_\mu(x) \, p^\mu f(x,p). \end{aligned} $

(24) Here,

$ f(x,p) $ is the phase-space distribution function of particles, and$ p^\mu = \left( E, {\boldsymbol{p}} \right) $ is their four-momentum with the mass-shell energy$ E = \sqrt{m^2 + {\boldsymbol{p}}^2} $ .The infinitesimal element of a three-dimensional freeze-out hypersurface from which particles are emitted

$ {\rm{d}}^3\Sigma_\mu(x) $ may be obtained from the formula (see, for example, Ref. [37])$ \begin{aligned} {\rm{d}}^3\Sigma_\mu = -\epsilon_{\mu \alpha \beta \gamma} \frac{\partial x^\alpha}{\partial a } \frac{\partial x^\beta }{ \partial b } \frac{\partial x^\gamma }{ \partial c }\, {\rm{d}} a\, {\rm{d}} b\, {\rm{d}} c, \end{aligned} $

(25) where

$ \epsilon_{\mu \alpha \beta \gamma} $ is the Levi-Civita tensor with the convention$ \epsilon_{0123}=-1 $ , and$ a, b, c $ are the three independent coordinates introduced to parametrize the hypersurface. This allows us to construct a six-dimensional, Lorentz-invariant density of the produced particles$ \begin{aligned} {\rm{d}}^{6}N = \frac{ {\rm{d}}^3 p}{E} \,\, {\rm{d}}^3\Sigma \cdot p \,\, f(x,p). \end{aligned} $

(26) The independent variables in such a general parametrization are the three components of three-momentum and the variables a, b, and c.

-

In local equilibrium, the distribution function

$ f(x,p) $ has the following general form$ \begin{aligned} f(x,p)= \frac{g_s}{(2\pi)^3}\left[ \Upsilon^{-1} \exp\left(\frac{p \cdot u}{T}\right)-\chi \right]^{-1}, \end{aligned} $

(27) where T is the freeze-out temperature,

$ \chi=-1 $ ($ \chi=+1 $ ) for Fermi-Dirac (Bose-Einstein) statistics, and$ g_s = 2s +1 $ is the degeneracy factor connected with spin. In this study, we use such distributions of protons and neutrons only (as input for the light nuclei coalescence formula); hence, we take$ \chi=-1 $ and$ s=1/2 $ . Since we use the same mass for protons and neutrons, their equilibrium distributions differ only by the values of thermodynamic potentials that determine the fugacity factor$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} \Upsilon_{{\rm{p}}} &= \exp \left( \frac{\mu_{{\rm{B}}} + \frac{1}{2} \mu_{{\rm{I}}_3}}{T}\right), \\ \Upsilon_{{\rm{n}}} &= \exp \left( \frac{\mu_{{\rm{B}}} - \frac{1}{2} \mu_{{\rm{I}}_3}}{T}\right). \end{split} \end{aligned} $

(28) Here,

$ \mu_{{\rm{B}}} $ and$ \mu_{{\rm{I}}_3} $ are the baryon and isospin chemical potentials, respectively. The values of T,$ \mu_{{\rm{B}}} $ , and$ \mu_{{\rm{I}}_3} $ for the considered expansions scenario are listed in Table 1. In the following, the distribution in Eq. (27) is used in the coalescence formula (Eq. (2)). -

In the case of freeze-outs that are spheroidally symmetric with respect to the beam axis, it is expedient to use the following parametrization of the spacetime points on the freeze-out hypersurface:

$ \begin{aligned} x^\mu(\zeta) = \left( t(\zeta), r(\zeta) \sqrt{1-\epsilon}\,{{\boldsymbol{e}}}_{r\perp}, r(\zeta) \sqrt{1+\epsilon}\, \cos\theta \right). \end{aligned} $

(29) Here,

$ {{\boldsymbol{e}}}_{r\perp} = \left( \cos\phi\sin\theta, \sin\phi \sin\theta\right) $ , and the parameter$ \epsilon\; $ controls deformation from a spherical shape. For$ \epsilon\; >\; 0 $ , the hypersurface is stretched in the (beam) z-direction. The resulting infinitesimal element of the spheroidally symmetric hypersurface has the form$ {\begin{aligned} {\rm{d}}^3\Sigma_\mu &= (1-\epsilon) \left( r^\prime \sqrt{1+\epsilon}, t^\prime \frac{\sqrt{1+\epsilon}}{\sqrt{1-\epsilon}}\,{{\boldsymbol{e}}}_{r\perp}, t^\prime \,\cos\theta \right) r^2 \sin\theta \, {\rm{d}}\theta\, {\rm{d}}\phi\, {\rm{d}}\zeta, \end{aligned}} $

(30) where the prime denotes the derivatives taken with respect to ζ. We also introduce the spheroidally symmetric hydrodynamic flow

$ \begin{aligned} u^\mu &= \gamma(\zeta,\theta)\left( 1, v(\zeta) \sqrt{1-\delta}\,{{\boldsymbol{e}}}_{r\perp}, v(\zeta) \sqrt{1+\delta}\,\cos\theta \right), \end{aligned} $

(31) where

$ \gamma(\zeta,\theta) $ is the Lorentz factor, which is given by the formula$ \begin{aligned} \gamma(\zeta,\theta) = \left[ 1-(1+\delta \cos(2 \theta))v^2(\zeta)\right]^{-1/2}, \end{aligned} $

(32) resulting from the normalization condition

$ u\cdot u=1 $ . The four-momentum of a hadron is parameterized as$ \begin{aligned} p^\mu = \left( E , p_\perp\cos{\phi_p} , p_\perp\sin{\phi_p}, p_\parallel\right), \end{aligned} $

(33) with

$ E=m_\perp \cosh(y) $ ,$ p_\perp = \sqrt{m_\perp^2-m^2} $ , and$ p_\parallel=m_\perp \sinh(y) $ . Thus, we obtain$ \begin{aligned} u \cdot p=\gamma(\zeta,\theta) \left[ E -\, v(\zeta) \kappa (\delta) \right] \end{aligned} $

(34) and

$ \begin{aligned} {\rm{d}}^3\Sigma \cdot p = \sqrt{1-\epsilon}\left( E \,r^\prime \sqrt{1-\epsilon^2} - t^\prime \kappa(-\epsilon) \right) r^2 \sin\theta \, {\rm{d}}\theta \, {\rm{d}}\phi \, {\rm{d}}\zeta, \end{aligned} $

(35) where

$ \kappa (\xi)= \sqrt{1+\xi}\, p_\parallel\cos\theta + \sqrt{1-\xi}\, p_\perp\sin\theta \cos(\phi-\phi_p) $ .Prior analyses of the spectra indicated that a satisfactory description of the data can be obtained by assuming

$ t^\prime=0 $ (which allows considering$ \zeta = r $ ),$ \epsilon=0 $ , and$ \delta \neq 0 $ . The flow profile is represented by$ v(r)=\tanh(H r) $ [38], where the value of the Hubble constant H is as given in Table 1. In this case,$ \begin{aligned} {\rm{d}}^3\Sigma \cdot p = E \, r^2 {\rm{d}} r \sin\theta \, {\rm{d}}\theta \, {\rm{d}}\phi , \end{aligned} $

(36) and the Cooper-Frye formula for fermions takes the form

$ \begin{aligned}\frac{\mathrm{d}N}{\mathrm{d}y\, m_{\perp}^2\mathrm{d}m_{\perp}} & =\cosh y\, \, \tilde{S}(p,\theta_p),\end{aligned} $

(37) where

$ {{\tilde S}(p,\theta_p)=\dfrac{g_s }{(2\pi)^2} \displaystyle\int\limits_0^R \mathrm{d}r \, r^2 \displaystyle\int\limits_0^\pi \mathrm{d}\theta \sin\theta \displaystyle\int\limits_0^{2\pi} \mathrm{d}\phi \left[\Upsilon^{-1} \exp\left( \dfrac{ u\cdot p }{T} \right) + 1 \right]^{-1}. }$

(38) The scalar product

$ u\cdot p $ is given by Eq. (34), and spherical symmetry allows us to consider$ \phi_p = 0 $ . Changing the variables from p and$ \theta_p $ to rapidity and transverse mass, we write$ \begin{aligned}\frac{\mathrm{d}N}{\mathrm{d}y\, m_{\perp}^2dm_{\perp}} & =\cosh y\, \, \tilde{S}\left[\sqrt{m_{\perp}^2\cosh^2y-m^2},\theta_y(m_{\perp},y)\right],\end{aligned} $

(39) where

$ \begin{aligned} \theta_y(m_\perp, y) = \arccos \frac{m_\perp \sinh y}{\sqrt{m_\perp^2 \cosh^2 y -m^2}}. \end{aligned} $

(40) Within our approximations, the angle in Eq. (40) is the same for nucleons and nuclei. In the zero-rapidity case,

$ \begin{aligned} \left. \frac{\mathrm{d}N}{\mathrm{d}y \, m_\perp^2 \mathrm{d}m_\perp} \right|_{y=0 }&= {\tilde S}\left(p_\perp, \frac{\pi}{2} \right). \end{aligned} $

(41) -

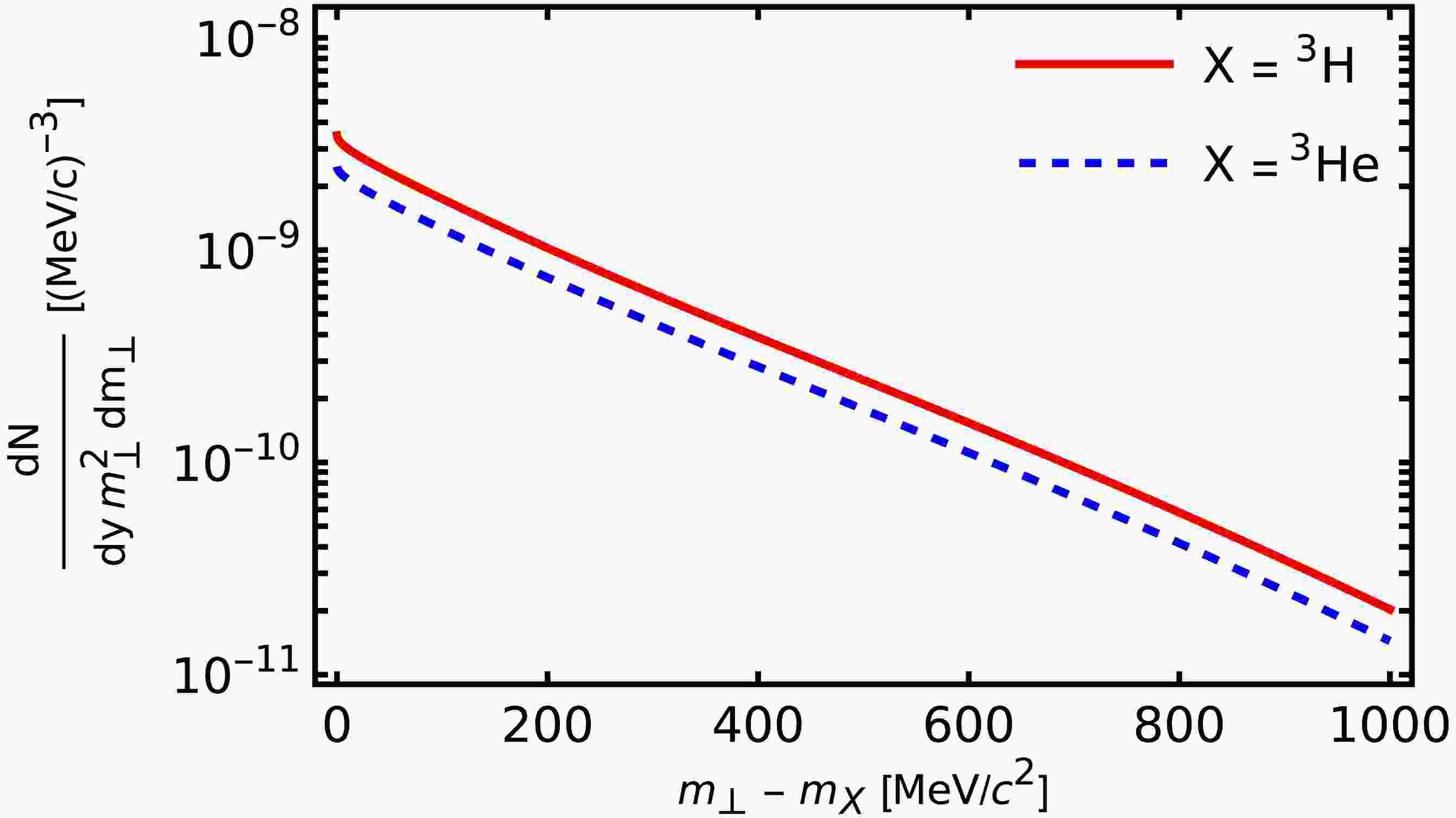

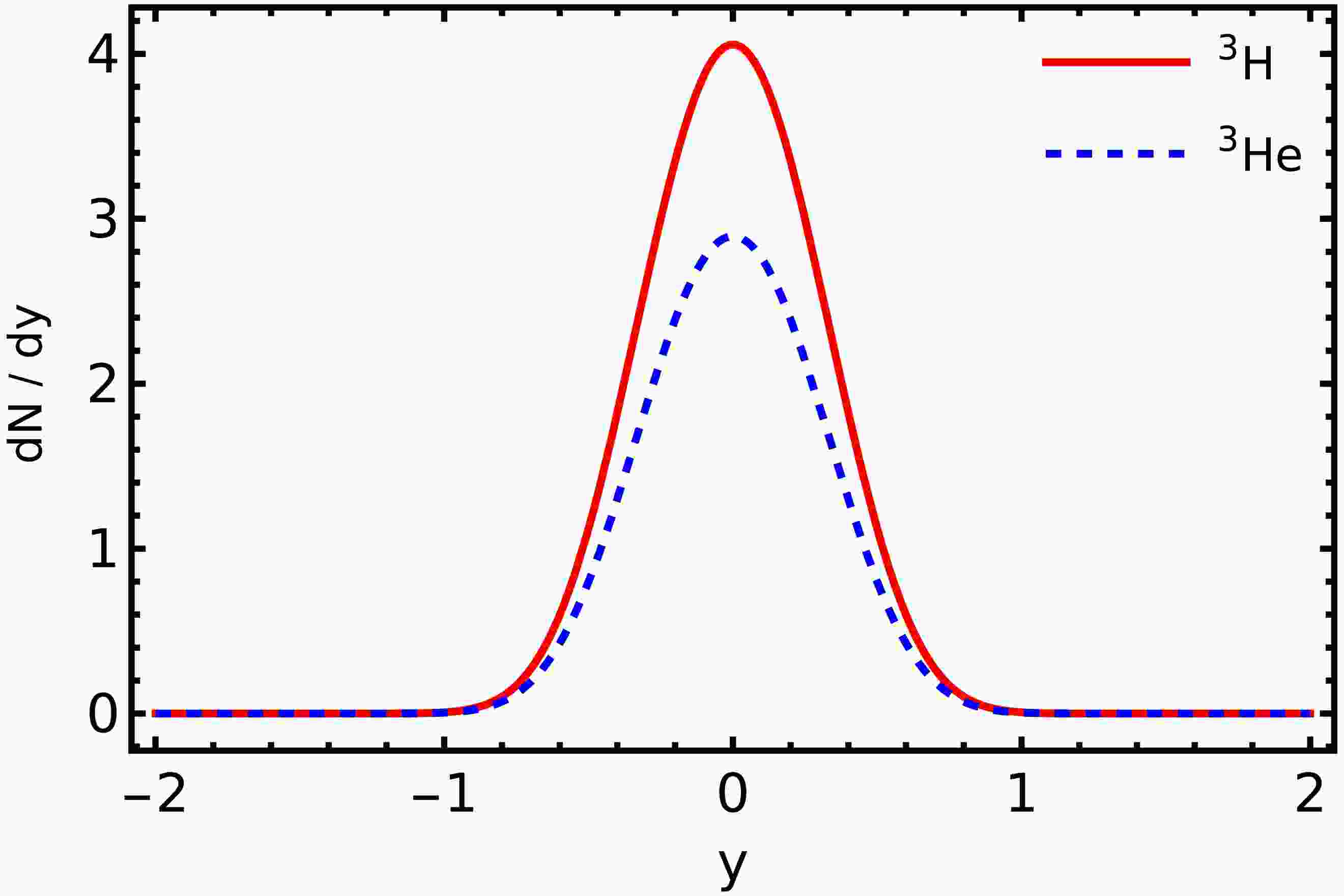

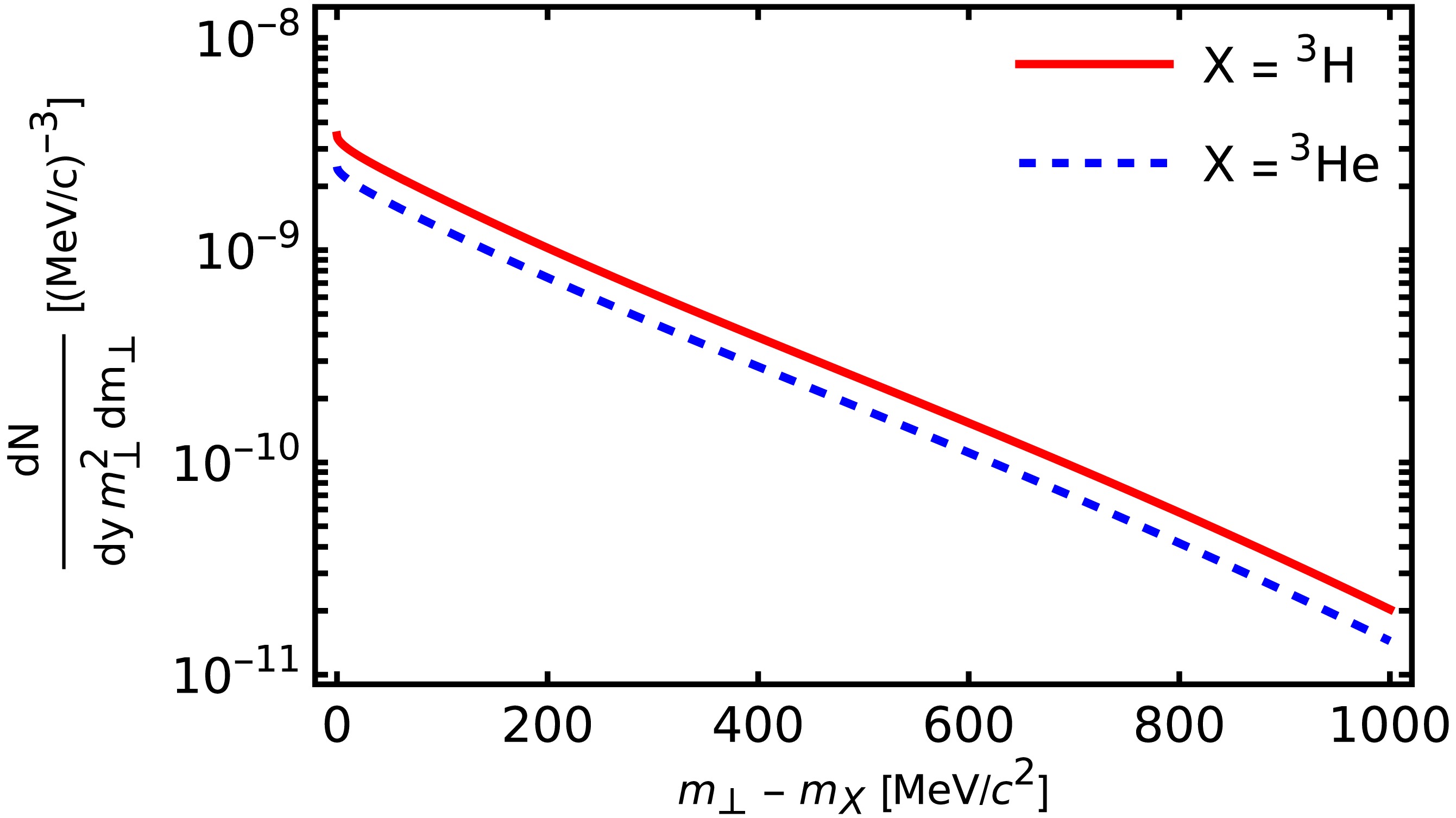

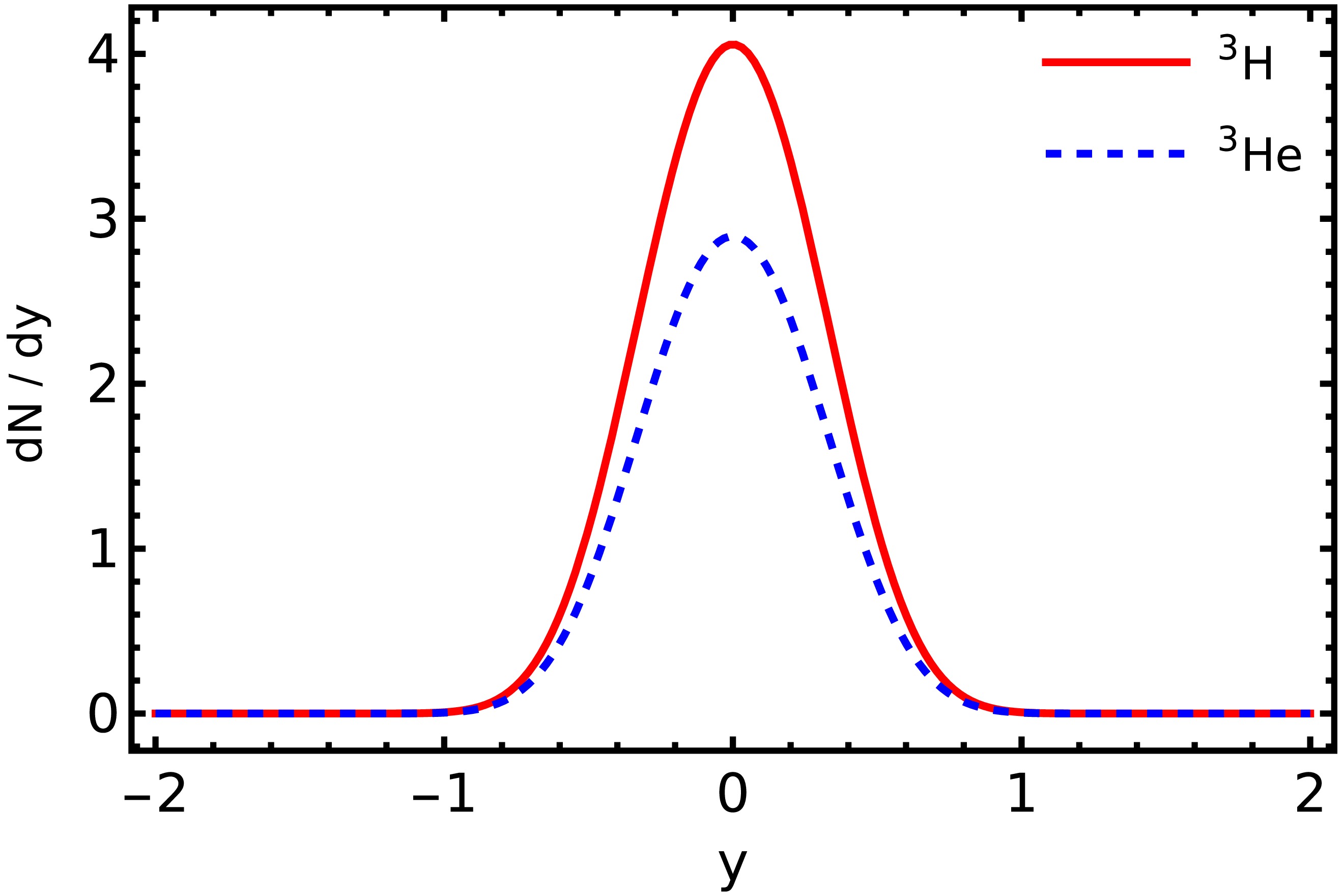

The model calculations of the spectra of 3H (

$ A=3, Z=1 $ ) and 3He ($ A=3, Z=2 $ ) nuclei are based on Eq. (5) with the nucleon distributions defined by Eq. (39), where we use different values of the fugacity factor Υ for protons and neutrons. Our results for the rapidity distributions and transverse-mass spectra are shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

Figure 3. (color online) Predicted transverse-mass spectra at zero rapidity for 3H (red solid line) and 3He (blue dashed line).

Figure 4. (color online) Predicted rapidity spectra of 3H (red solid line) and 3He (blue dashed line).

Integrating the spectra, we find the total yields, which we compare with the experimental results in Table 3. We observe that the model calculations underestimate the experimental results by factors of 2.7 and 2.0 (for 3H and 3He, respectively). The main uncertainty of the theoretical results comes from the formation rate factors that are calculated in a relatively simple manner, as described in Sec. II B. More realistic calculations of the formation rate may improve the agreement with the data (here, we consider, for example, more realistic forms of the wave functions). We note that the values of the coefficients

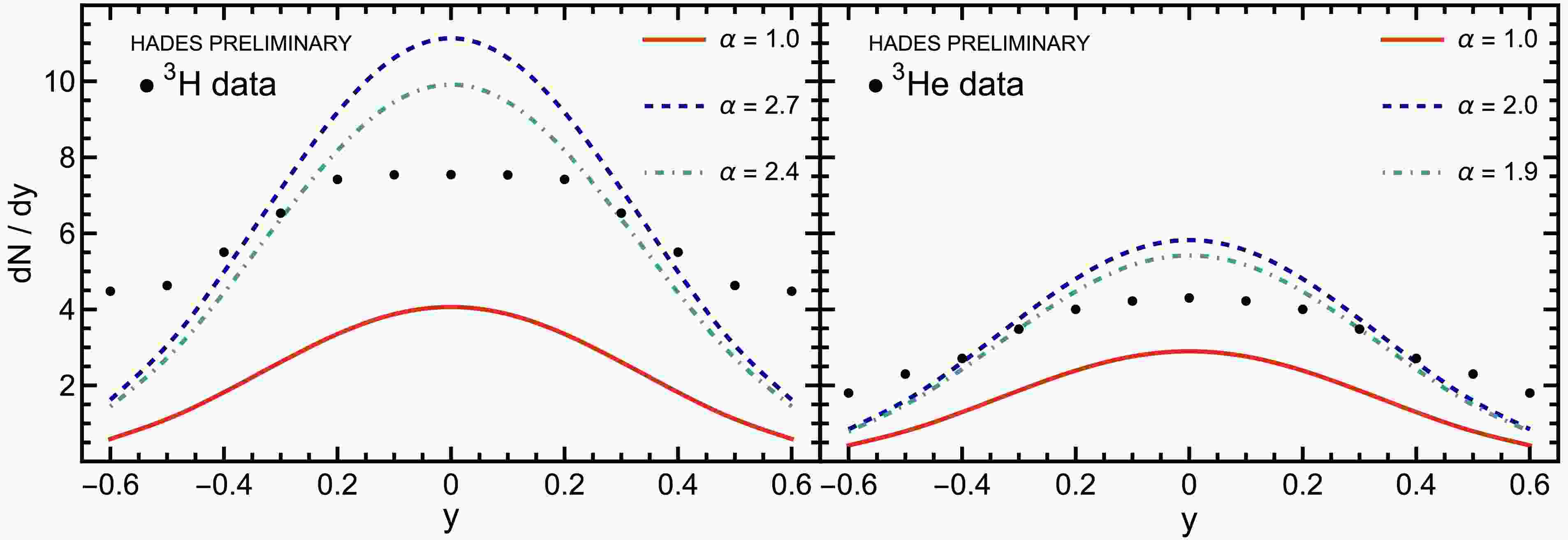

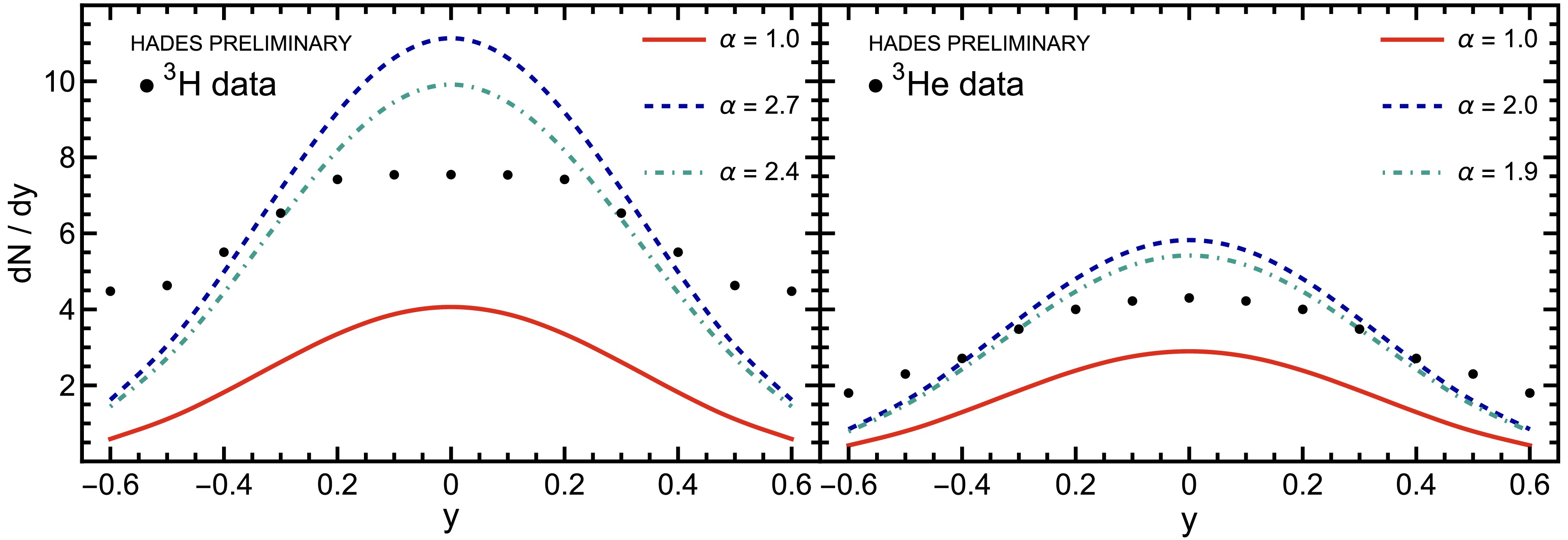

$ A_{{\rm{FR}}} $ are very large (see Table 2), which means that our final results are products of very large and small numbers (all in units of MeV). Therefore, it is quite intriguing that we correctly reproduce the order of magnitude of the yields. This is achieved by the assumption that the coalescence takes place just after freeze-out within a sphere of radius R. We note that other theoretical frameworks, for example, IQMD + MST, also underestimate the yields; see Refs. [39, 40].Additional verification of the model can be obtained from a comparison of the rapidity and transverse-momentum spectra. In fact, very often only the correct description of the shapes of the spectra of composite particles is regarded as the indication that the coalescence mechanism is at work. To check whether we can reproduce the rapidity profiles of the preliminary HADES data [8, 9], we have varied the values of

$ A_{{\rm{FR}}} $ by rescaling them by a factor α (compared to the original values derived above). In the case of the rapidity distribution of 3H, the best description is obtained for$ \alpha = 2.3 $ , which is slightly smaller than the factor 2.7 needed to reproduce the experimental yield. For 3He, the best adjustment is obtained for$ \alpha = 1.7 $ , compared to the factor 2.0 found above to fit the yield, see Fig. 5.3 The corresponding total multiplicities are given in Table 4, where we also show the dependence on the integration range in rapidity.

Figure 5. (color online) Rapidity spectra prediction for 3H (left) and 3He (right) for different scaling factors: exact model value (red solid line,

$ \alpha =1.0 $ ), fit to the experimental yield (blue dashed line,$ \alpha =2.7 $ for 3H and$ \alpha =2.0 $ for 3He), and best fit to data (teal dash-dotted line,$ \alpha =2.4 $ for 3H and$ \alpha =1.9 $ for 3He). The data shown are preliminary HADES results [8, 9].On account of the uncertainty of the normalization of the experimental transverse-mass spectra, we have refrained from making comparisons between theory and experiment in this case. However, we observe that the slopes of our model for the

$ m_{\perp} $ -distributions are steeper than those shown as preliminary results. -

In this study, we use the previously constructed model of hadron production in heavy-ion collisions in the few-GeV energy regime [1, 2, 4] to determine the yields and spectra of 3H and 3He. Our approach combines the thermal framework with single freeze-out with the concept of coalescence of emitted nucleons. This approach proves to be very successful in determining the yield of 2H [4]. The present study extends the previous framework to the next lightest nuclei. Our predictions for the yields of 3H and 3He are smaller by factors of 2.7 and 2.0 than the experimental values, respectively. Despite this discrepancy, it is noteworthy that our simple model correctly describes the order of magnitude of the multiplicities studied. We also note that the model yield values are controlled by the formation rate factors

$ A_{{\rm{FR}}} $ , whose calculation can be improved in the future by using more realistic wave functions of 3H and 3He. The comparison of the preliminary HADES results on the spectra shows that we are missing a factor of approximately 2 to reproduce the rapidity spectra.Since a similar factor is missing to reproduce the yields of both 3H and 3He, our approach effectively reproduces the experimental ratio of these two yields. The importance of the studies of such ratios has been recently stressed in Ref. [41]. Finally, we note that there might be other sources of light nuclei production that enhance their yields, such as the break-up of spectator nuclei [28, 42]. However, such a mechanism is not included in our model, which describes the production of particles in the participant zone only.

-

We thank Małgorzata Gumberidze, Szymon Harabasz, and Piotr Salabura for useful discussions concerning the experimental data.

3H and 3He nuclei production in a combined thermal and coalescence framework for heavy-ion collisions in the few-GeV energy regime

- Received Date: 2025-04-05

- Available Online: 2026-01-15

Abstract: A thermal model describing hadron production in heavy-ion collisions in the few-GeV energy regime is combined with the concept of nucleon coalescence to make predictions for the production of 3H and 3He nuclei. A realistic parametrization of the freeze-out conditions is employed, which accurately reproduces the spectra of protons and pions. It also correctly predicts the deuteron yield, which agrees with experimental observations. However, the predicted yields of 3H and 3He are lower than the experimental results by approximately a factor of two. The model predictions for the spectra can be compared with future experimental data.

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: