-

Although general relativity (GR) has achieved much success in classical scenarios, it still encounters significant challenges under extreme conditions [1, 2]. The singularity theorems of Penrose and Hawking indicate that GR loses its predictive ability in certain regions, which has prompted physicists to propose alternative theories of gravity or consider quantum effects to eliminate singularities. [3−9]. The Einstein-Cartan theory avoids the appearance of singularities by introducing torsion [10]; quantum gravity frameworks such as string theory and loop quantum gravity provide a completely new explanatory perspective for avoiding the problem of spacetime singularities [11−15]. In addition, the Einstein-Yang-Mills theory, by unifying non-Abelian gauge fields and gravity within the geometrized framework of curved spacetime, provides a new tool for studying the interactions between gauge and gravitational fields in complex backgrounds [16−19]. This theory not only expands the scope of application of GR but also has significance in describing asymptotic symmetries, black hole physics, and the research on quantum gravity [20]. The proposal of alternative theories of gravity has provided new concepts for overcoming the limitations of GR under extreme conditions.

The black hole, one of the classic predictions of GR, is not only an important tool for verifying existing gravitational theories but also a crucial experimental object for testing the validity of alternative theories and distinguishing differences among theories. In recent years, the exploration of black holes has been at the forefront of theoretical physics research. With the release of the images of the supermassive black hole M87* by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) in 2019 [21−26] and the images of the supermassive black hole SgrA* at the center of the Milky Way in 2022 [27], the existence of black holes has been conclusively proven. The images released by the EHT clearly indicate an obviously dark region in the central part of the black hole. Often, this specific dark region is called the shadow of the black hole. The shadow is the region inside the critical curve, which is closely related to the radially unstable spherical photon orbit [28]. Meanwhile, the shadow is also a prominent feature of the image of the accretion flow around supermassive black holes [29]. The shape and size of the shadow depend on the spacetime metric. The research on black hole shadows provides us with an important method for extracting effective information about black hole spacetime and testing various alternative theories of gravity. After Synge's pioneering work [30], many studies on black hole shadows have been conducted using various gravitational theories [31−39].

A bright ring surrounds the black hole shadow. This bright ring is called the photon ring [40]. It is an important concept in the research on black hole imaging. Through the strong gravitational lensing effect, the light around the black hole is repeatedly deflected around it and finally forms photon trajectories successively [41]. These photon trajectories together present a ring-shaped image around the black hole. This phenomenon not only provides crucial clues for black hole imaging but also serves as an important tool for studying physical phenomena in the extreme environment near black holes. Through observations of the photon ring, researchers have gained a deeper understanding of the properties of black holes, such as the structure of the accretion disk, gravitational lensing effect, and rotation speed of black holes [33, 42−44]. The photon ring provides a method for testing the no-hair theorem of black holes [45]; studying the gravitational effects of black holes [46]; and extracting information about black hole parameters such as mass, spin, and event horizon size [47]. In addition, research on the higher-order ring images of black hole accretion disks has enabled their use in distinguishing different accretion models [48]. Therefore, the observational images of the photon rings and shadows of black holes are effective tools [49] for better understanding the properties of black holes.

The no-hair theorem indicates that a black hole can often be described by three physical parameters, namely mass, angular momentum, and electric charge. Therefore, although the internal conditions before the formation of a black hole may be extremely complicated, it becomes a relatively simple celestial body after its formation. However, for modified theories of gravity, the introduction of modification terms adds extra degrees of freedom, which can explain phenomena that are difficult to be fully explained by GR. When exploring modified theories of gravity, researchers are committed to introducing additional matter fields into the theoretical system. The introduction of these additional matter fields has produced a significant result, that is, a black hole can no longer be characterized solely by the traditional three parameters but requires more "hairy" parameters to fully describe its properties. Consequently, hairy black holes, as new research objects, have been widely constructed and deeply analyzed in related fields [33, 50−54].

Recently, Gómez et al. obtained a spherically symmetric solution of the Einstein-Maxwell theory in the presence of the Yang-Mills field with a power term [55]. Although their work did not include a detailed discussion on the stability of this black hole solution, they studied the quasi-normal modes of this four-dimensional Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole, which, to some extent, reflects the local stability of the black hole spacetime. Subsequently, they investigated the conditions under which matter accretion can occur around this black hole [55], thereby validating the astrophysical feasibility of the theory. These studies prompt us to investigate the effects of the Yang-Mills field on black hole spacetime by studying the black hole photon ring. Specifically, we focus on the model with the power term

$ p=1/2 $ and electric charge term$ Q=0.6 $ (the optical appearance of the uncharged power-Yang-Mills black hole case for this specific$ p=1/2 $ scenario has been previously studied in [56]). This special case represents a black hole that has both Abelian charges Q and non-Abelian charges$ q_{\rm YM} $ and is asymptotically non-flat. When our Yang-Mills hair parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ is set to zero, it reverts to the standard Reissner-Nordström (RN) black hole solution. Therefore, this paper analyzes this model and leverages the structural characteristics of the photon ring and shadow mentioned earlier. Because the structural characteristics of the photon ring and shadow differ among black hole solutions, we expect that the changes in these characteristics can be used to distinguish different black hole solutions, thereby testing the Yang-Mills hair.The remainder of this paper is structrured as follows. In Section II, the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole solution is presented. Moreover, the value scenario of the event horizon of this black hole under the action of the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ is explored. In Section III, the geodesic equation of the hairy black hole is first derived. Thereafter, the constraints on the hair parameter are provided based on existing observational data, followed by a discussion of variations in the effective potential with the hair parameter. In Section IV, we employ the ray-tracing method to investigate the photon trajectories around the hairy black hole. Furthermore, we systematically study the optical appearance of the black hole illuminated using three thin accretion disk models to examine the influence of the hairy parameter on the image characteristics. Subsequently, we conduct a comparative analysis between the optical appearances in the nonlinear case ($ p=1/2 $ ) and standard Yang-Mills case ($ p=1 $ ) to explore the effects of nonlinearity. Section V presents the summary. In addition, throughout this paper, the natural unit system is adopted, i.e.,$c = G = 1$ , and$M = 1$ is set. The metric signature$(-, +, +, +)$ is used in this paper. -

In this section, we first briefly introduce the static and spherically symmetric hairy black hole under the standard Einstein-Maxwell theory with the p-power Yang-Mills term. The total action contains three parts: i) The Einstein-Hilbert term, ii) Maxwell invariant, and iii) Power Yang-Mill invariant. It can be expressed as follows:

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} S_0 = \frac{1}{2}\int \sqrt{-g}\ \text{d}^4x \Bigg[ & R - {\cal{F}}_{\rm M} - {\cal{F}}_{\rm YM}^{p} \Bigg], \end{split} \end{aligned} $

(1) where g is the determinant of the metric tensor

$ g_{\mu \nu} $ , R is the Ricci scalar, and p is a real parameter that introduces nonlinearties. The Maxwell and power-law Yang-Mills terms can be expressed as follows [55]:$ {\cal{F}}_{\rm M} = F_{\mu \nu} F^{\mu \nu} ,$

(2) $ {\cal{F}}_{\rm YM}={\rm{Tr}} (F_{\lambda \sigma}^{(a)}F^{(a)\lambda \sigma})=\sum_{a = 1}^{3}(F_{\lambda\sigma}^{(a)}F^{(a)\lambda\sigma}) . $

(3) Here,

$ F_{\mu \nu} $ is the electromagnetic field tensor, and$ F_{\mu \nu}^{(a)} $ is the Yang-Mills field strength tensor. We consider the spherically symmetric spacetime (in Schwarzschild coordinates), and the line element of this black hole can be expressed as [49]$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} {\rm d} s^{2}=-f(r) {\rm d }t^{2}+f(r)^{-1} {\rm d }r^{2}+r^{2}\left({\rm d} \theta^{2}+\sin ^{2} \theta {\rm d }\varphi^{2}\right) \end{split}, \end{aligned} $

(4) where

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} f(r)=1-\frac{2 M}{r}+\frac{Q^{2}}{r^{2}}+\frac{Q_{\rm YM}}{r^{4p-2}} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(5) This solution can be understood as a linear combination of the Yang-Mills term and standard RN solution, and the Yang-Mills charge

$ q_{\rm YM} $ is related to its normalized version as [57]$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} Q_{\rm YM} \equiv \frac{2^{p - 1}}{4p - 3} q_{\rm YM}^{2p} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(6) Eq. (5) shows that, compared with the standardized RN black hole solution, the metric in this paper introduces only a nonlinear parameter p and hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ . Their introduction indicates the geometric deformation on the radial and time metric components.Furthermore, when considering different values of the power exponent p, we find that the satisfaction of the energy conditions exhibits distinct differences [57, 58]. For

$ p<0 $ , all energy conditions are violated. However, when$ 3/4<p<3/2 $ , all energy conditions are satisfied. For other values of p, the energy conditions are only partially satisfied; for example, when$ p=1/2 $ , only the weak and strong energy conditions are satisfied, whereas the dominant, causality, and null energy conditions are violated [57, 58]. Nevertheless, owing to the existence of classical and quantum field theories, a special phenomenon emerges: Even if some energy conditions are violated, they can still be consistent with the experimental data [59, 60]. Take the non-minimally coupled scalar field theory with positive curvature coupling as an example. The violation of energy conditions means that traversable wormholes may exist [61]. Moreover, in various alternative theories of gravity, the introduction of additional degrees of freedom has resulted in new gravitational dynamical mechanisms. Under their influence, the corresponding energy conditions also exhibit unique characteristics [62]. Considering multiple aspects, the case of$ p=1/2 $ has research significance. Therefore, in this work, this scenario is selected as the core research object, and a comprehensive and in-depth analysis is conducted. The case of$ p=1/2 $ not only presents a simple feature in theoretical form, which adds convenience to the research work and effectively reduces the complexity of the research, but more importantly, against the complex research background of astrophysics, it shows intricate and close connections with numerous physical phenomena and frontier theoretical models [55]. Based on its unique advantages and important research value, the case of$ p=1/2 $ undoubtedly should be the focus of our attention. Meanwhile, we also determine that the value of Q is 0.6.Therefore, when the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM}=0 $ , it can revert to the standard RN black hole solution. Because this metric is static and spherically symmetric, the event horizon, as a hypersurface with spacetime symmetry, should also be static and spherically symmetric. When solving for the event horizon, it should only be a function of r, independent of t, θ, and φ. In other words, the event horizon should satisfy$ \begin{aligned}\begin{split}g^{rr}=0\end{split};\end{aligned} $

(7) thus, we obtain

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} f(r) = 1 - \frac{2M}{r} + \frac{Q^2}{r^2} + \frac{Q_{\rm YM}}{r^{4p - 2}} = 0 \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(8) When we determine the values of the power term

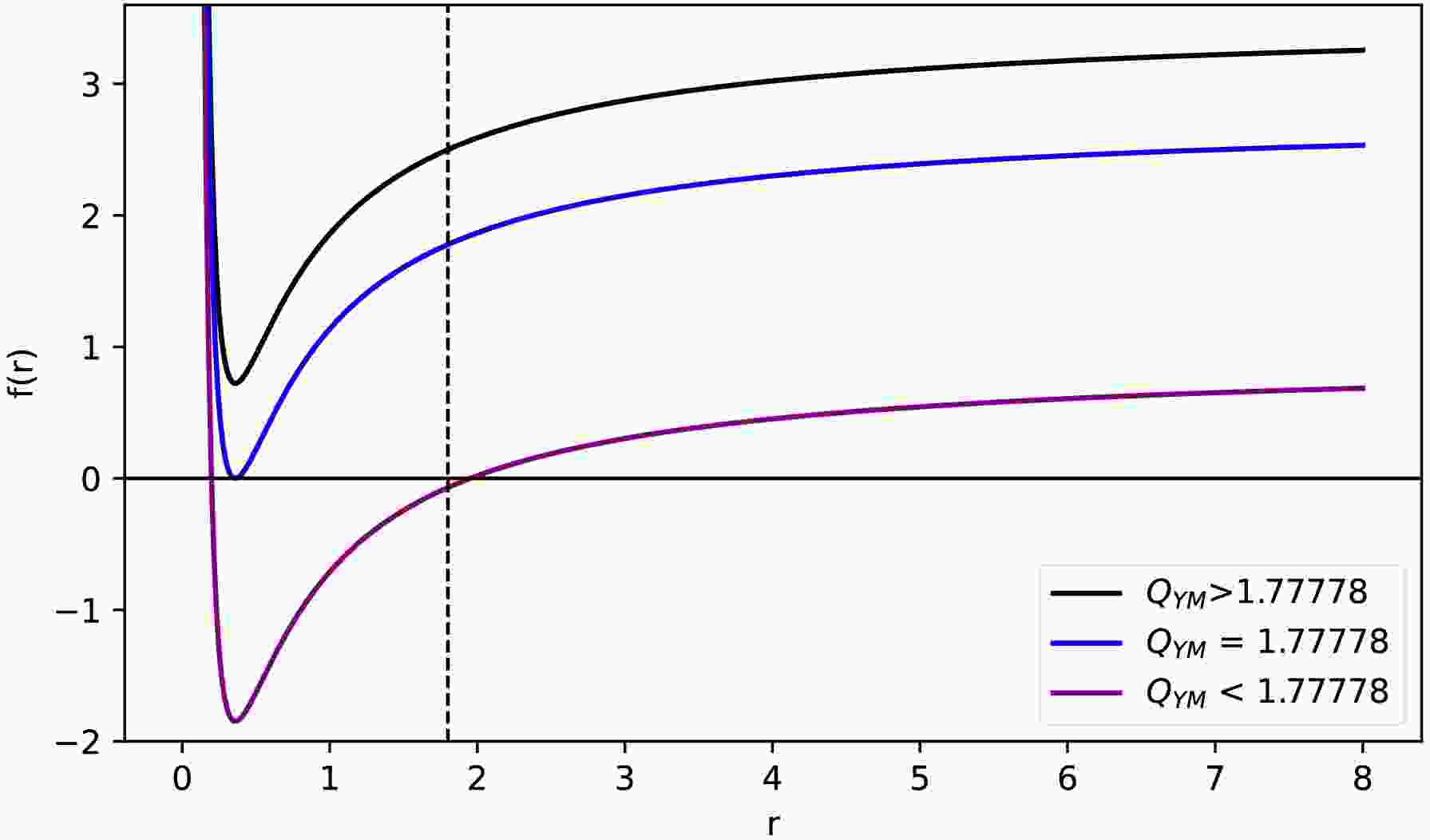

$ p=1/2 $ and Abelian charge$ Q=0.6 $ , solving Eq. (8) can yield the horizon scenarios under different$ Q_{\rm YM} $ values, and they are shown in Fig. 1. The black dashed line in the figure represents the position of the event horizon radius of the RN black hole. We find that when$ Q_{\rm YM}=1.77778 $ , one root corresponds to the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole with only one horizon. When$ Q_{\rm YM} $ is less than this value, the black hole will have two horizons; conversely, when$ Q_{\rm YM} $ is greater than this value, no horizon exists. -

To study the influence of the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ of the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole on the photon ring and shadow, we must first study the equation of motion of photons in the spacetime of this black hole and discuss the effective potential of photons. In the spherically symmetric spacetime, we consider the photon motion constrained to a fixed plane,$ \theta = \pi/2 $ , that is,$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} \sin \theta = 1, ~\frac{{\rm d} \theta}{{\rm d} \tau} = 0 \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(9) For the spacetime of the line element (4), the geodesic equation can be derived according to the Lagrangian

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} 2 {\cal{L}} = g_{ij} \frac{{\rm d}x^i}{{\rm d}\tau} \frac{{\rm d}x^j}{{\rm d}\tau} \end{split}, \end{aligned} $

(10) where τ is the affine parameter along the geodesic. From the spacetime metric, the Lagrangian is

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} {\cal{L}} = \frac{1}{2} \left[ - f(r) \dot{t}^2 + \frac{1}{f(r)} \dot{r}^2 + r^2 \dot{\theta}^2+ (r^2 \sin^2 \theta) \dot{\varphi}^2 \right] \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(11) Here, the dot indicates the derivative with respect to τ, and the corresponding canonical momenta are

$ \begin{aligned}[b] p_{t} &= \frac{\partial {\cal{L}}}{\partial \dot{t}} = - f(r) \dot{t},\\ p_{r} &= - \frac{\partial {\cal{L}}}{\partial \dot{r}} = - \frac{1}{f(r)} \dot{r},\\ p_{\theta} &= - \frac{\partial {\cal{L}}}{\partial \dot{\theta}} = - r^{2} \dot{\theta},\\ p_{\varphi} &= - \frac{\partial {\cal{L}}}{\partial \dot{\varphi}} = - r^{2} \sin^{2} \theta \dot{\varphi}. \end{aligned} $

(12) The Schwarzschild spacetime has two Killing vector fields, namely the timelike Killing vector field

$ \left( \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \right)^a $ and axial Killing vector field$ \left( \dfrac{\partial}{\partial \varphi} \right)^a $ . These two Killing vector fields will lead to two conserved quantities, that is, the conservation of energy E and conservation of angular momentum L [46].$ E= - g_{00} \frac{{\rm d} t}{{\rm d} \tau} = f(r) \frac{{\rm d} t}{{\rm d} \tau} , $

(13) $ L = g_{33} \frac{{\rm d} \varphi}{{\rm d} \tau} = r^2 \frac{{\rm d} \varphi}{{\rm d} \tau} . $

(14) By substituting Eqs. (13) and (14) into Eq. (11), we obtain

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} 2 {\cal{L}} = -\frac{E^2}{f(r)} + \frac{1}{f(r)} \dot{r}^2 + \frac{L^2}{r^2} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(15) Additinally, because the Lagrangian of the null geodesic is zero,

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} \frac{1}{f(r)} \left( \frac{{\rm d} r}{{\rm d} \tau} \right)^2 = \frac{E^2}{f(r)} - \frac{L^2}{r^2} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(16) From Eq. (16), an ordinary differential equation for the radius r with respect to the azimuthal angle φ in the orbital plane can be further obtained [47]:

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} \left( \frac{{\rm d} r}{{\rm d} \varphi} \right)^2 = r^4 \left( \frac{1}{b^2} - V_{\rm eff}(r) \right) \end{split}, \end{aligned} $

(17) where

$ b \equiv L/E $ is the impact parameter, and$ V_{\rm eff} $ is the effective potential for the radial motion of the photon, which can be expressed as$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} V_{\rm eff}(r)= f(r) \frac{1}{r^2} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(18) We observe that the photon trajectory is determined by the impact parameter b. To study the black hole shadow, we must determine the radius of the unstable photon sphere, which is determined by the following equation [44, 63]:

$ \left. V_{\rm eff}(r) \right|_{r = r_{\rm ph}} = \frac{1}{b_{\rm ph}^2} , $

(19) $ \left. \frac{{\rm d} V_{\rm eff}(r)}{{\rm d}r} \right|_{r = r_{\rm ph}} = 0. $

(20) After obtaining the radius of the photon sphere from Eq. (20), substituting it into Eq. (19) will yield the corresponding critical impact parameter as

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} b_{\rm ph} = \frac{r_{\rm ph}}{\sqrt{f(r_{\rm ph})}} \end{split}, \end{aligned} $

(21) with

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} r_{\rm ph} = \frac{3 + \sqrt{9 - 8 Q^2 - 8 Q^2 Q_{\rm YM}}}{2 (1 + Q_{\rm YM})} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(22) The critical impact parameter

$ b_{\rm ph} $ is the threshold distance at which light rays are captured by the black hole. It typically corresponds to the boundary of the shadow of a static black hole in the observer's field of view. From Eq. (21), we know that the critical impact parameter$ b_{\rm ph} $ depends on the metric function$ f(r) $ and, consequently, is also related to the parameters Q and$ Q_ {\rm YM} $ . Therefore, we use the existing observational data on the shadows of the supermassive black holes M87* and Sgr A* to constrain the hair parameter.The EHT observations reveal that the possible shadow diameter of M87* is

$ d_{\rm sh}^{\rm M87^*}=(11\pm1.5) $ , whereas the shadow diameter of Sgr A* is$ d_{\rm sh}^{\text{Sgr A}^*}=(9.5\pm1.4) $ . For the Einstein-Maxwell power-law Yang-Mills black hole, the shadow diameter$ d_{\rm sh} $ can be derived from Eq. (21); we obtain$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} d_{\rm sh}=2\frac{r_{\rm ph}}{\sqrt{f(r_{\rm ph})}} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(23) Thus, we present the constraints on the parameters Q and

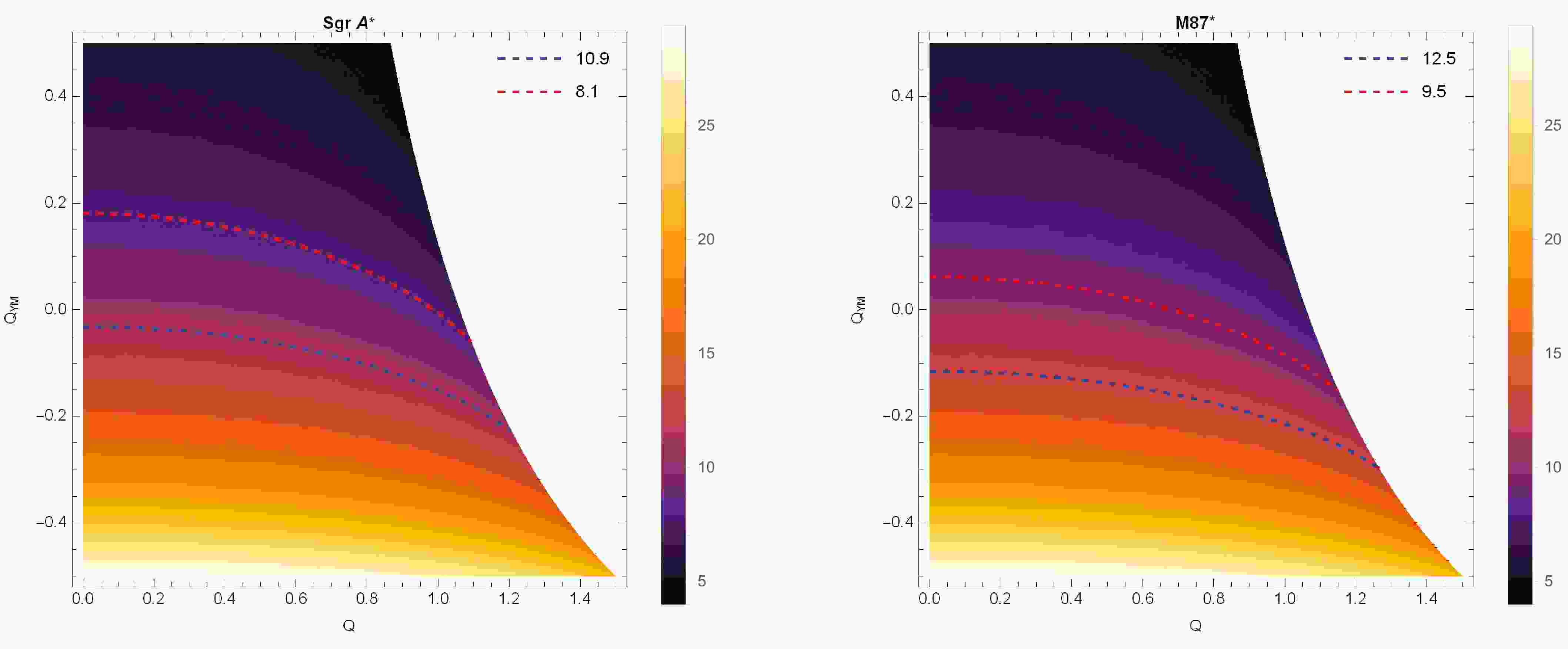

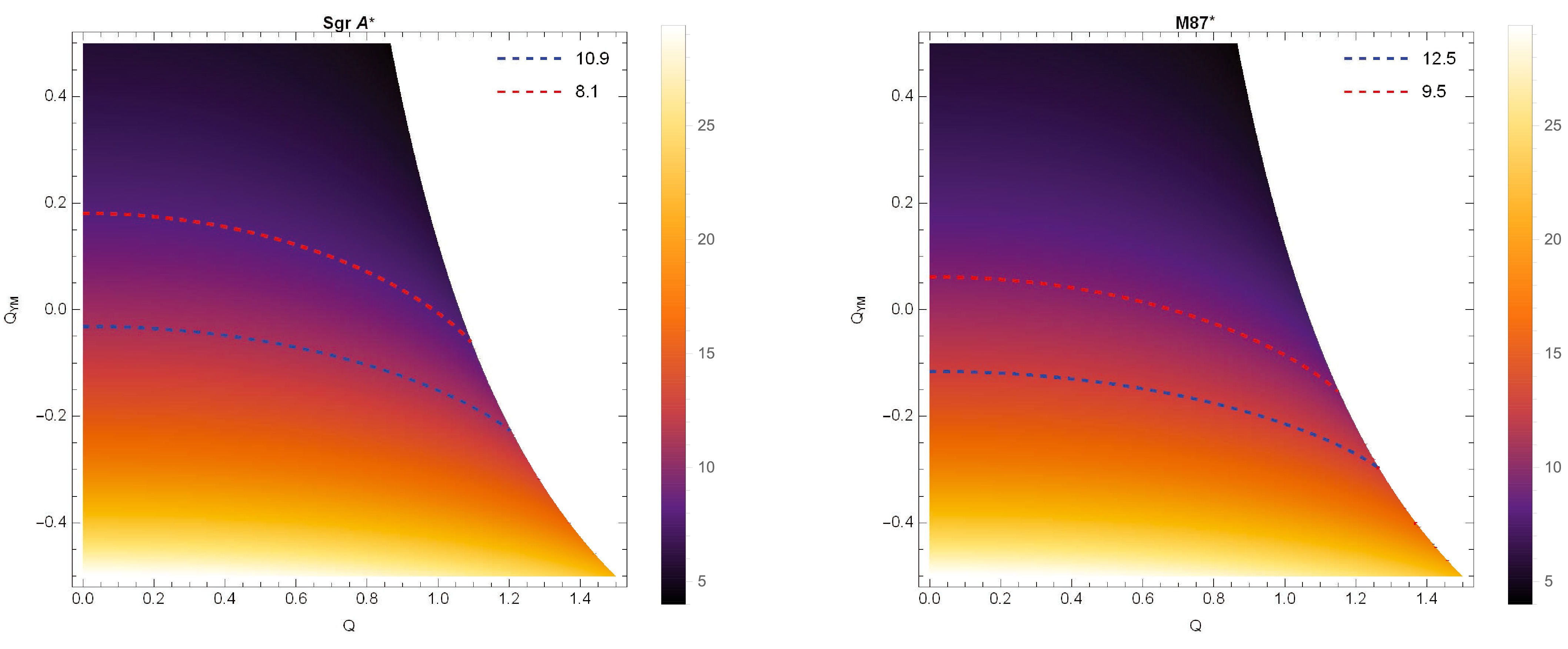

$ Q_{\text{\rm YM}} $ under the observational bounds from M87* and Sgr A* in Fig. 2. In the constrained ranges of Q and$ Q_{\rm YM} $ shown in Fig. 2, we clearly observe that as the charge Q increases, the allowable range of$ Q_{\rm YM} $ that satisfies the observational data constraints gradually shrinks. Moreover, in each subplot of Fig. 2, a blank region appears on the right side, corresponding to combinations of Q and$ Q_{\rm YM} $ for which the shadow diameter$ d_{\rm sh} $ does not exist.

Figure 2. (color online) Constraints on parameters Q and

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ from observational data of Sgr A* (left-hand panel) and M87* (right-hand panel). The red and blue dashed lines represent the upper and lower bounds of the observed shadow diameters for Sgr A* and M87*, respectively.Subsequently, we specify the scenario considered in this work by fixing the electric charge at

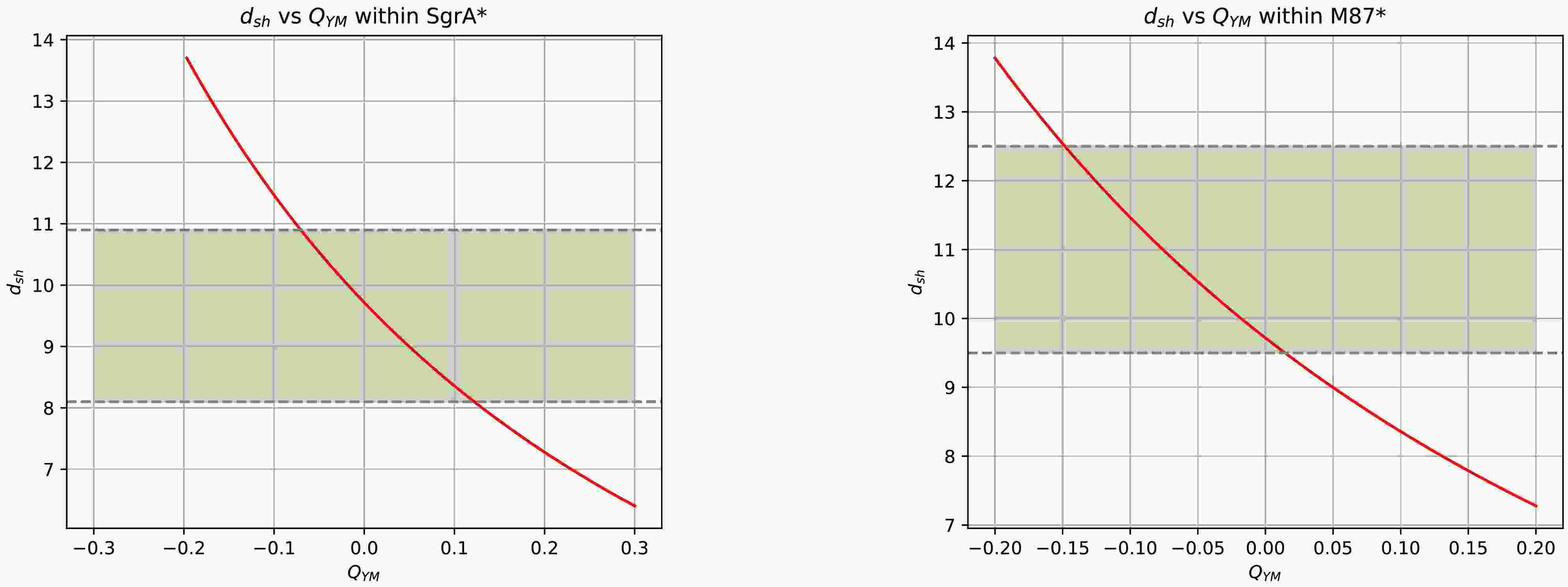

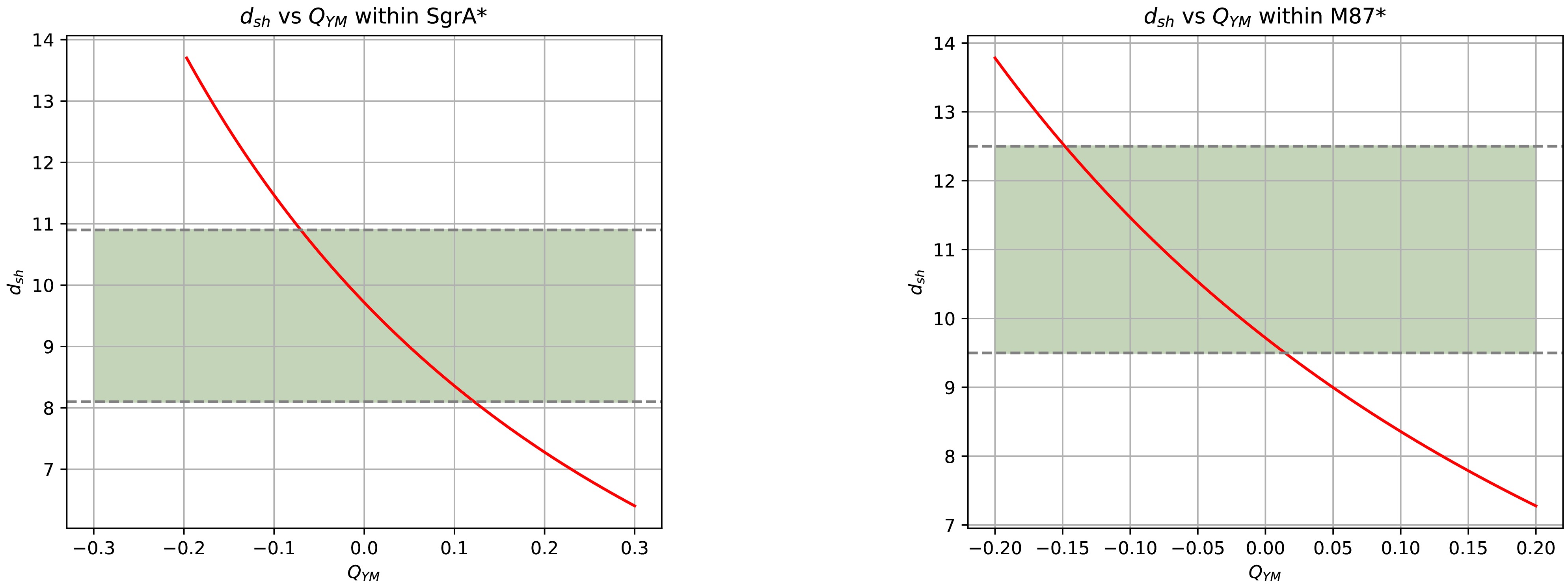

$ Q=0.6 $ while examining the observational constraints on the hair parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ imposed by Sgr A* and M87*, as shown in Fig. 3. From Fig. 3, we observe that under the observational constraints of Sgr A*, the allowable range for the hair parameter is$ -0.07 \leq Q_{\rm YM} \leq 0.12 $ , whereas for M87*, the permitted range becomes$ -0.15 \leq Q_{\rm YM} \leq 0.02 $ . Consequently, our subsequent analysis will be restricted to the interval$ -0.07 \leq Q_{\rm YM} \leq 0.02 $ .

Figure 3. (color online) Constraints on the hair parameter from EHT observations of Sgr A* (left-hand panel) and M87* (right-hand panel). The red curve represents the variations in the shadow diameter with the hair parameter, and the green region indicates the possible range based on EHT observations.

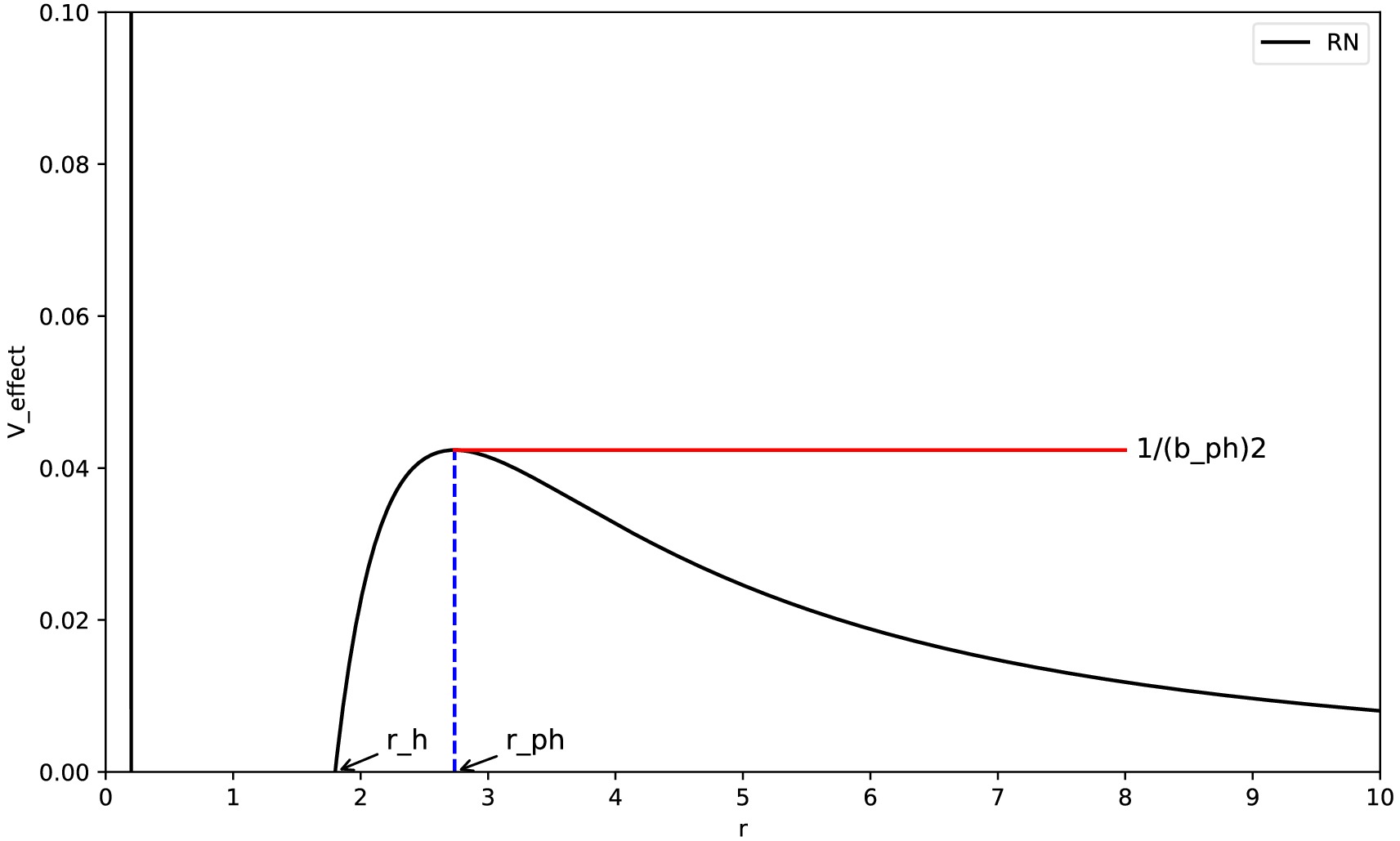

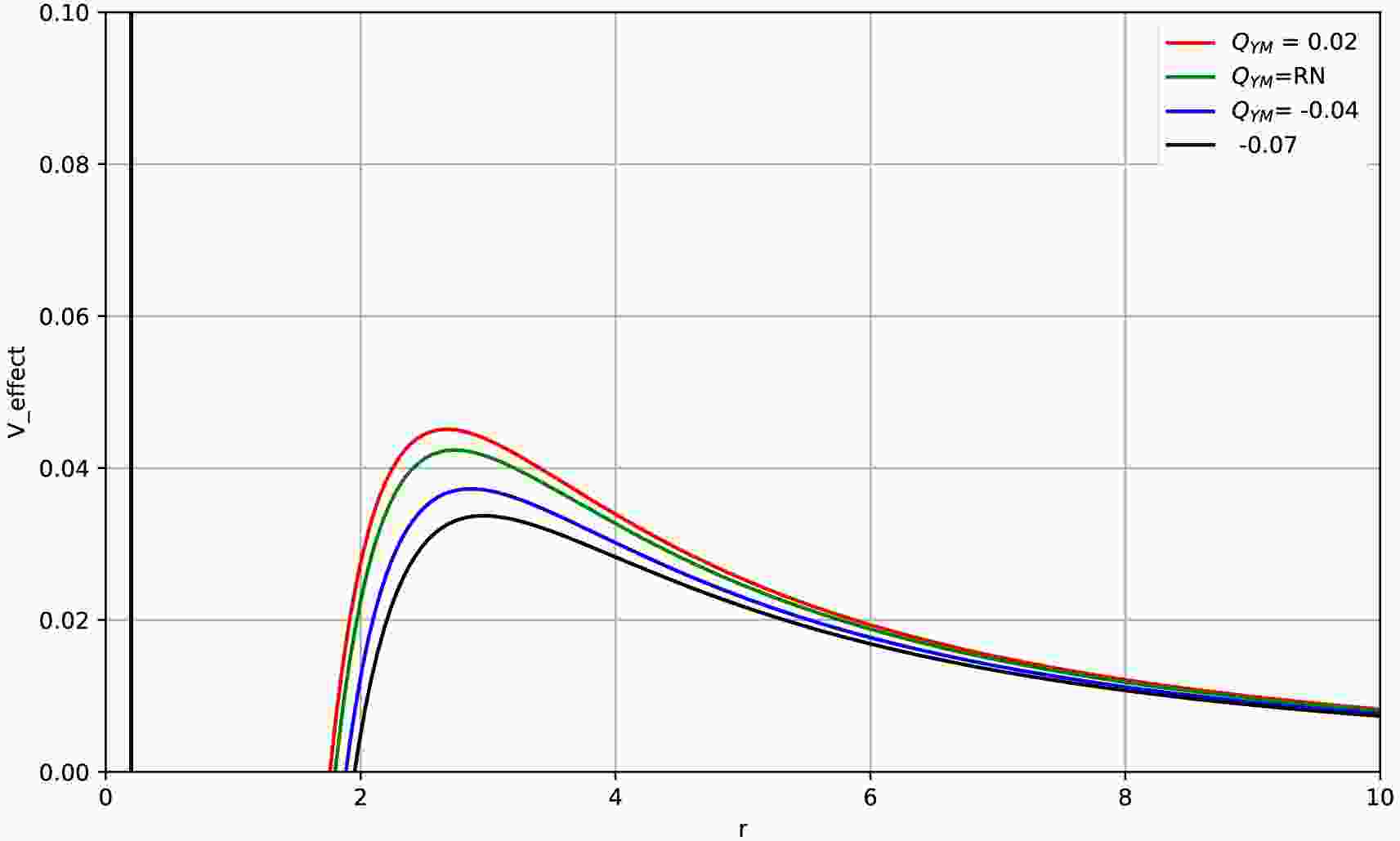

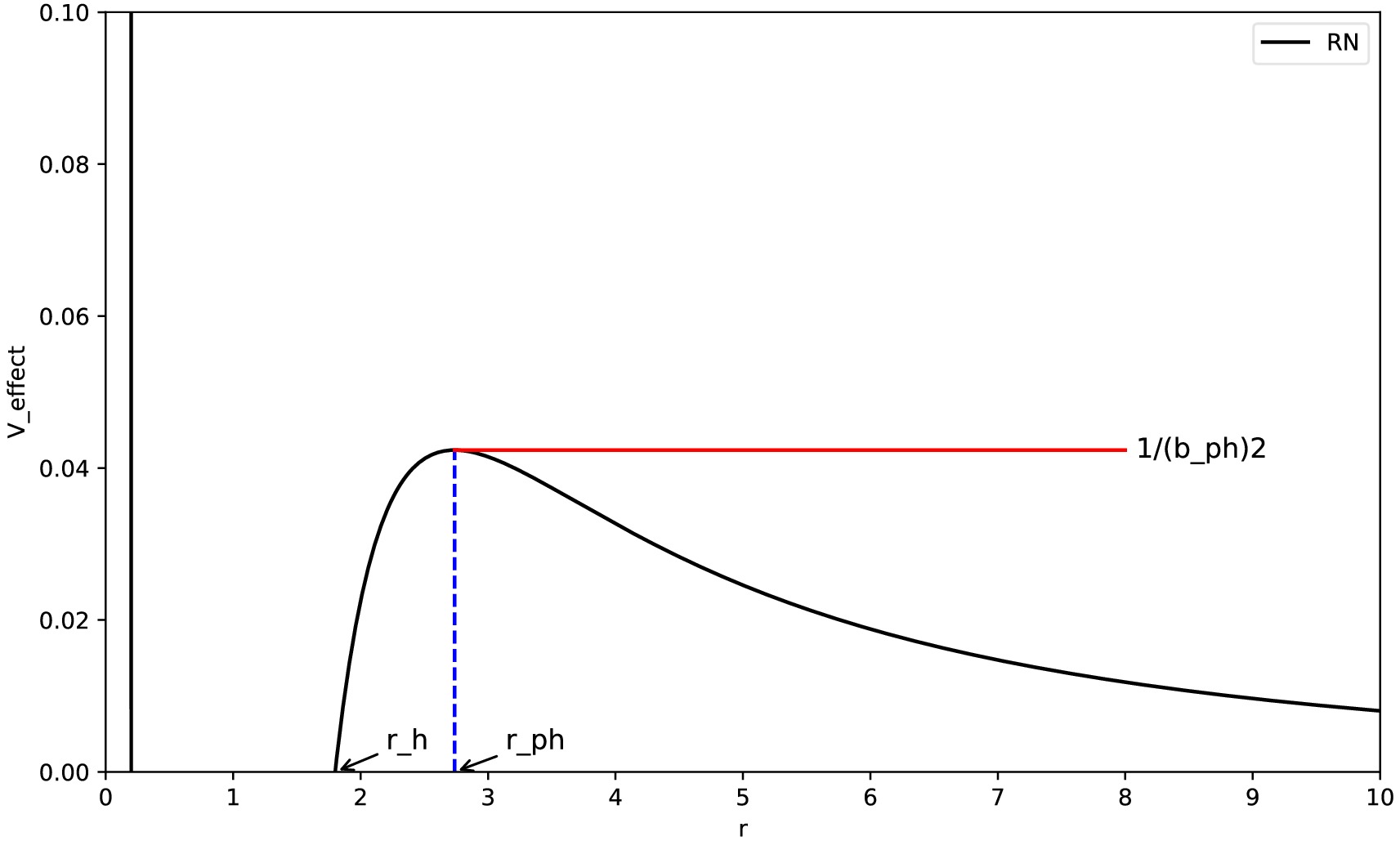

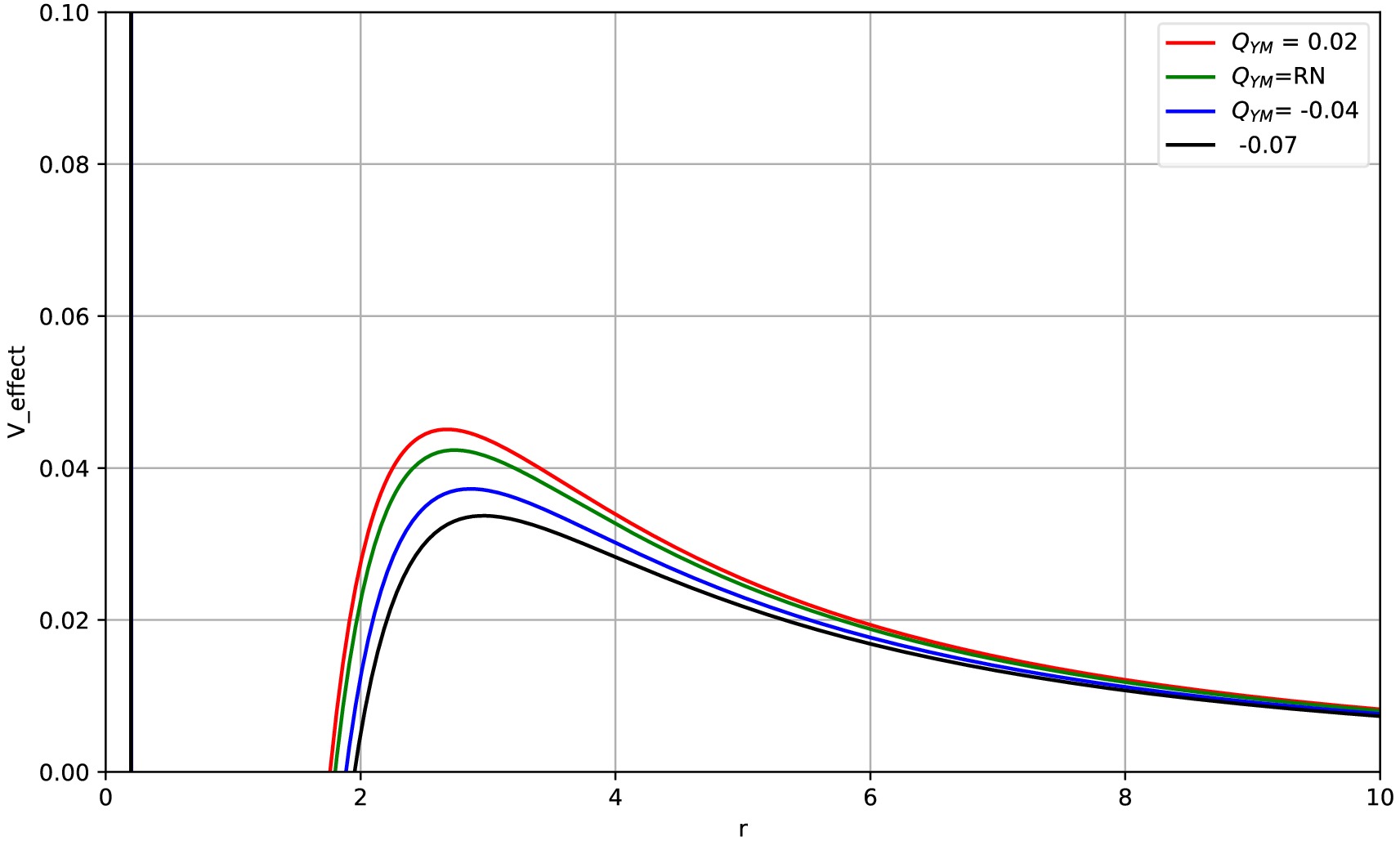

The effective potential

$ V_{\rm eff} $ for the radial motion of photons can be used to distinguish different photon orbits. To understand the relationship between the effective potential$ V_{\rm eff} $ , photon sphere radius$ r_{\rm ph} $ , and critical impact parameter$ b_{\rm ph} $ , we use the RN black hole as an example and illustrate their relative positions in Fig. 4. In the figure, for an RN black hole with$ Q=0.6 $ , the event horizon radius is$ r_{\rm h}=1.8 $ , photon sphere radius is$ r_{\rm ph}=2.7369 $ , and critical impact parameter is$ b_{\rm ph}= $ 4.8586. The maximum value in the figure represents the radius of the unstable photon sphere. Furthermore, we show the photon effective potential images for different hairy parameters$ Q_{\rm YM} $ in Fig. 5. We easily observe from Fig. 5 that as$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, the photon effective potential gradually increases, and the event horizon radius of the black hole and photon sphere radius of the photons also decrease.

Figure 4. (color online) Effective potential

$ V_{\rm eff}(r) $ of an RN black hole with$ Q=0.6 $ as a function of r, along with the relationship between the photon sphere radius$ r_{\rm ph} $ and critical impact parameter$ b_{\rm ph} $ .

Figure 5. (color online) Variation in the effective potential

$ V_{\rm eff}(r) $ with r for$ Q=0.6 $ and different values of the hair parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ , including$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.07 $ ,$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.04 $ ,$ Q_{\rm YM}=0.02 $ , and the RN case.The value of the effective potential is significant in studying photon orbits. When the effective potential reaches its maximum value, the corresponding orbit is an unstable photon sphere. When photons on such an orbit are slightly disturbed, they may either fall into the black hole or escape to infinity and be captured by distant observers. Conversely, when the effective potential takes on a minimum value, the orbit at this time is stable, allowing photons to move continuously and stably on the corresponding orbit. The unstable photon sphere that can be transmitted to distant observers has an important influence on observing the characteristics of the accretion image [64]. Therefore, in the following discussion, we focus on the unstable photon sphere orbits.

-

The fine structure of the photon ring involves the complex behaviors of photon orbits near black holes, particularly the distribution of photons on different orbits. Because photons on different orbits appear as layers with different brightnesses when imaged, observers can easily identify the characteristics of black holes. We adopt the method of backward ray-tracing to analyze the behaviors of null geodesics near the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills hairy black hole and further explore the optical appearance of the black hole when a very thin accretion disk is the light source. Here, the accretion disk is idealized as an optically and geometrically extremely thin plane, that is, the disk surface has no absorption or scattering effects on photons. During the research process, we assume that the background radiation has no impact on the results and the accretion disk is the only light source. To simplify the analysis, we fix the accretion disk on the equatorial plane and assume that the observer is located in the direction of the North Pole at the same time. Owing to the strong gravitational pull of the black hole, the null geodesics of photons may intersect with the accretion disk multiple times before falling into the black hole or escaping to infinity. The difference in the number of such intersections will have an important impact on the total light intensity received by the observer. Therefore, we must classify these light rays according to the number of intersections between the null geodesics and accretion disk and calculate the imaging effect of the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills hairy black hole based on this.

-

To facilitate the study of the motion trajectories of photons near black holes, we perform a transformation on Eq. (17) with

$ r = 1/u $ ; thus, the geodesic equation of photons becomes$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} \left( \frac{{\rm d}u}{{\rm d}\varphi} \right)^2 = \frac{1}{b^2}-f\left( \frac{1}{u} \right)u^2 \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(24) As shown in Eq. (24), the motion trajectory of photons is closely related to the impact parameter b, as discussed in [46]. For all null geodesics that are parallelly directed towards the North Pole, the range of their impact parameters depends on the number of intersections between the null geodesics and accretion disk, and the number of intersections can be expressed as

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} n = \frac{\varphi}{2 \pi} \end{split}, \end{aligned} $

(25) in the formula, φ is the total change in the polar angle in the polar coordinate system during the completion of the entire trajectory of the null geodesic.

From Eq. (24), when

$ b < b_{\rm ph} $ , the total change in the polar angle outside the event horizon is given by [44]$ \varphi = \int_0^{u_{\rm h}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\dfrac{1}{b^2}-f\left( \dfrac{1}{u} \right)u^2}} {\rm d}u . $

(26) Here,

$ u_{\rm h} \equiv 1/r_{\rm h} $ , and$ r_{\rm h} $ is the radius of the event horizon. When$ b > b_{\text{\rm ph}} $ , the total change in the polar angle is$ \varphi = 2 \int_0^{u_{\text{max}}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\dfrac{1}{b^2}-f\left( \dfrac{1}{u} \right)u^2}} {\rm d}u . $

(27) Here,

$ u_{\text{max}} \equiv 1/r_{\text{min}} $ , and$ r_{\rm min} $ is the minimum radial distance from the position of the light ray on its trajectory to the black hole. To discuss the observational images of radiation near a black hole, we must clarify that the observed intensity is closely related to the number of intersections between geodesics and the accretion disk, and the number of intersections n is a function of b satisfying such a relationship [65].$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} n(b)=\frac{2m - 1}{4}, \quad m = 1,2,3,\cdots. \end{split} \end{aligned} $

(28) Eq. (28) shows that for a given m, we use

$ b_m^{\pm} $ to represent two different solutions [46, 65], where$ b_m^{-} < b_c $ and$ b_m^{+} > b_c $ . Thus, we can classify all trajectories as follows:• Direct emission:

$ 1/4<n<3/4 $ $ \Leftrightarrow $ $ b\in(0,b_2^-)\cup (b_2^+,\infty) $ ;• Lensing ring:

$ 3/4<n<5/4 $ $ \Leftrightarrow $ $ b\in(b_2^-,b_3^-)\cup(b_3^+,b_2^+) $ ;• Photon ring:

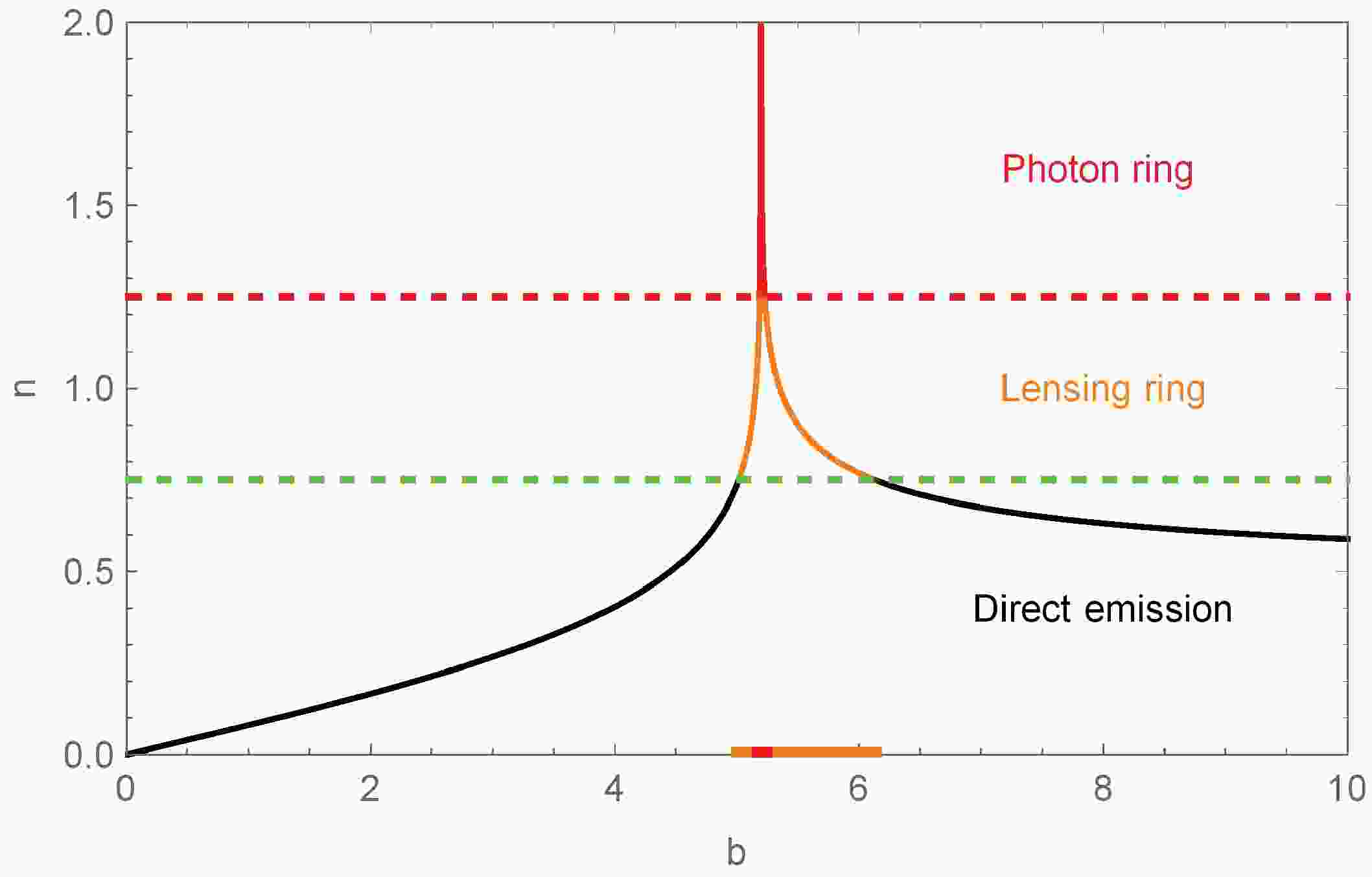

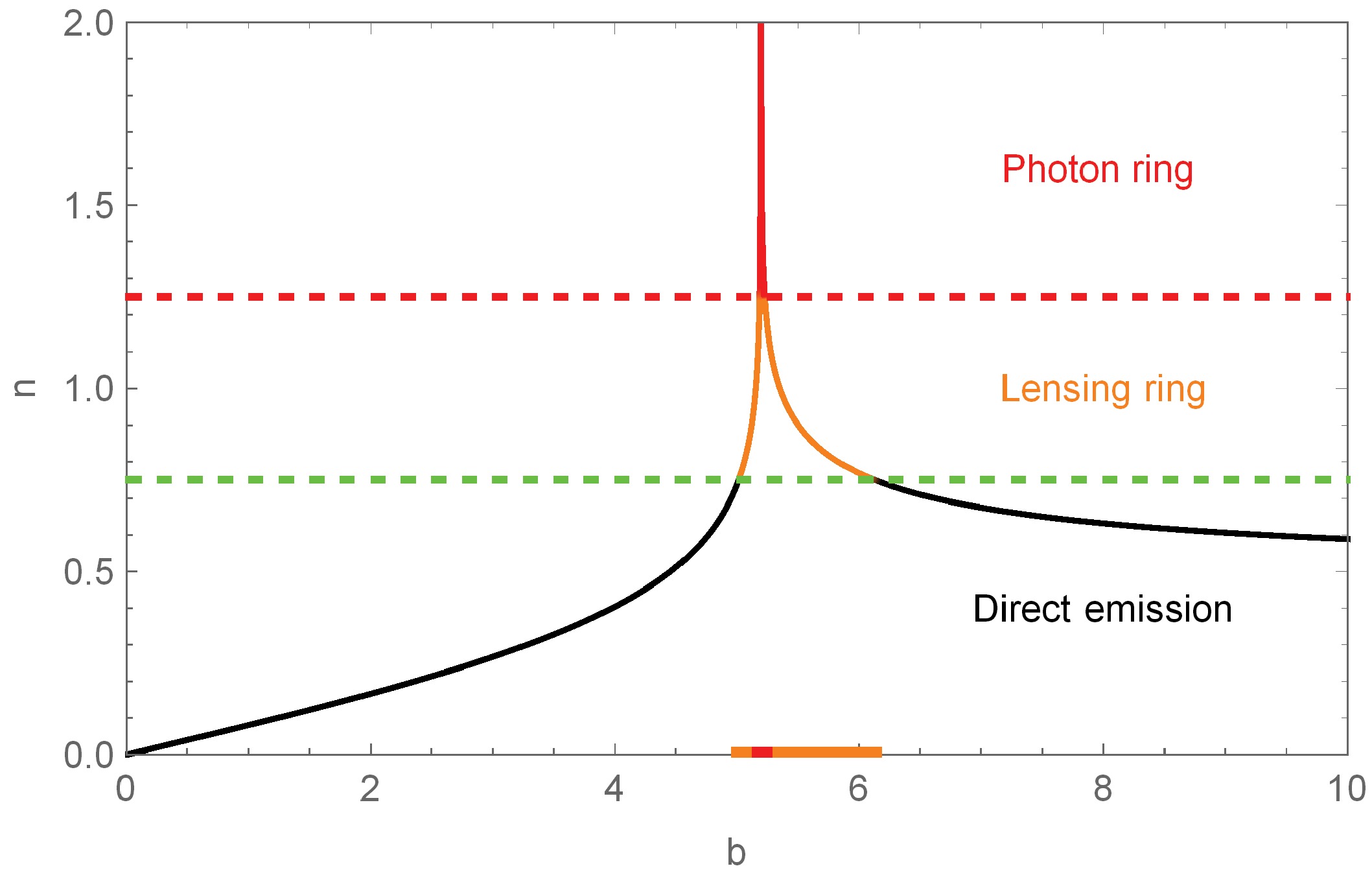

$ n>5/4 $ $ \Leftrightarrow $ $ b\in(b_3^-,b_3^+) $ .Fig. 6 presents the variation curve of the number of intersections n of null geodesics of an RN black hole with the accretion disk with respect to the impact parameter b when

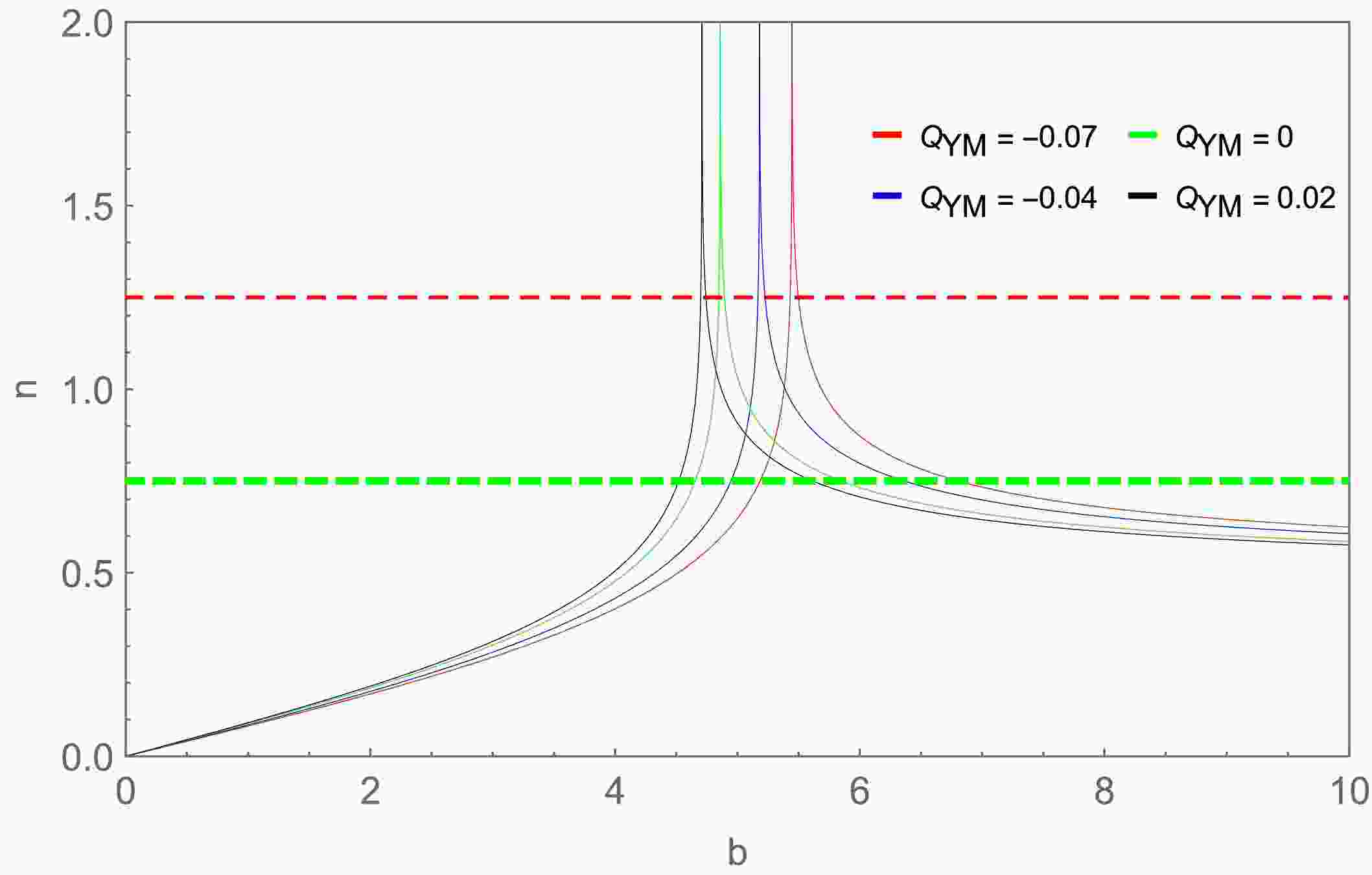

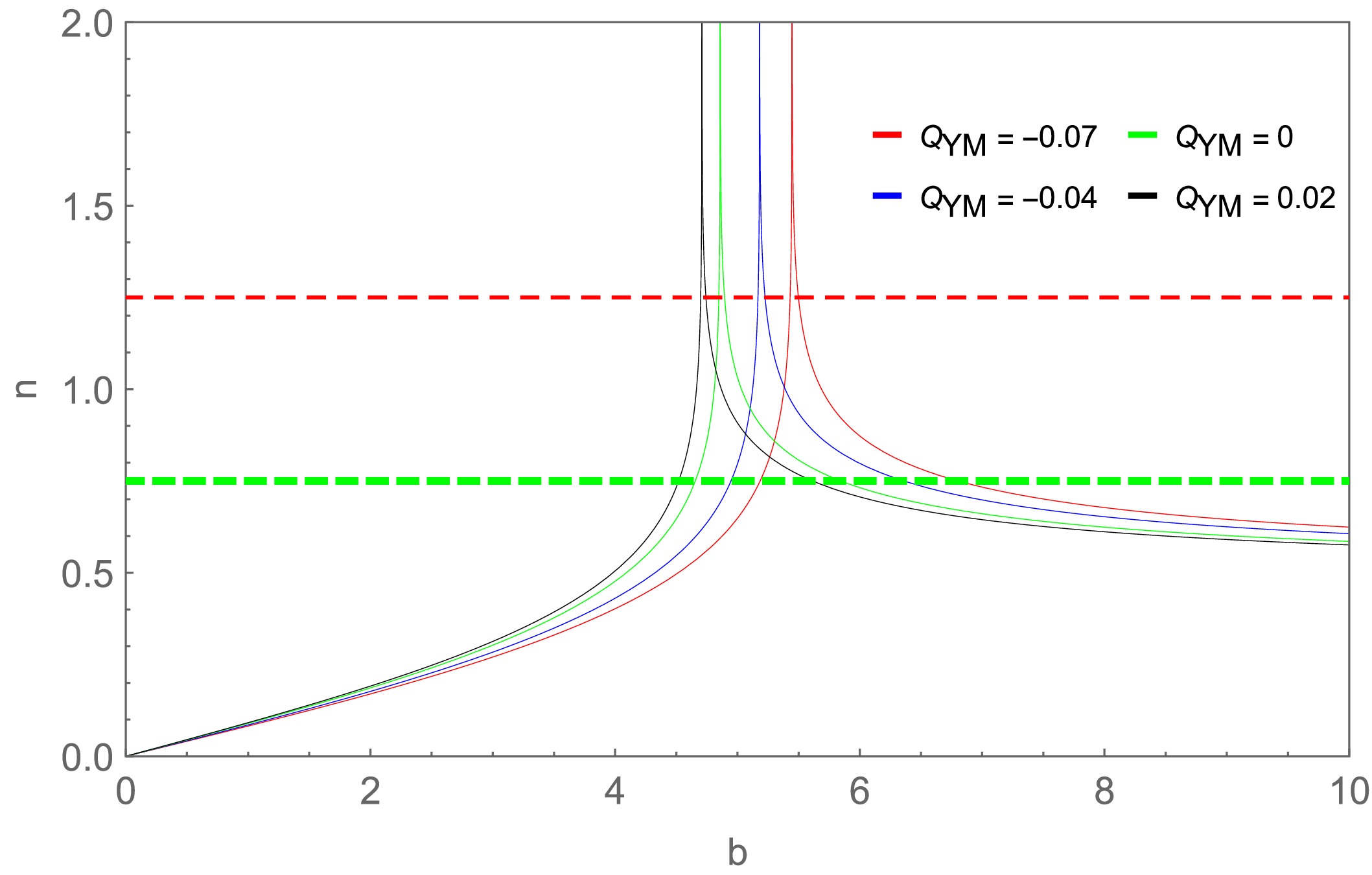

$ Q=0.6 $ . The black line in the figure represents the photon trajectory of direct emission, orange line represents the lensing ring, and red line represents the photon ring. We observe that when the impact parameter is less than the critical impact parameter, the number of intersections increases as the impact parameter increases, reaching a maximum at the critical parameter, and the opposite is true when the impact parameter is greater than the critical impact parameter. Similarly, using the null geodesic equation of photons, Eq. (24), we present in Fig. 7 the variation relationship between the number of intersections n of null geodesics with the accretion disk and the impact parameter b for different values of the hairy parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ when$ Q=0.6 $ . Fig. 7 shows that the variation trend of the number of intersections n of null geodesics with the accretion disk with respect to the impact parameter b for different values of$ Q_{\rm YM} $ is similar to that of the RN case. However, as$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, the entire variation curve shifts to the left, which corresponds to the fact that the critical impact parameter gradually decreases as$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases. Moreover, the impact parameter intervals corresponding to the lensing and photon rings also gradually decrease as$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases.

Figure 6. (color online) Variation curve of the number of intersections n with the impact parameter b for an RN black hole when

$ Q=0.6 $ . The black, orange, and red lines represent the direct emission, lensing ring, and photon ring, respectively.

Figure 7. (color online) Relationship between the number of intersections n of null geodesics with the accretion disk and the impact parameter b for different values of the hair parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ :$ 0.02 $ (black),$ 0 $ (green),$ -0.04 $ (blue), and$ -0.07 $ (red).In addition, by using the null geodesic Eq. (24), we have plotted the light ray trajectory diagrams near the black hole for different values of

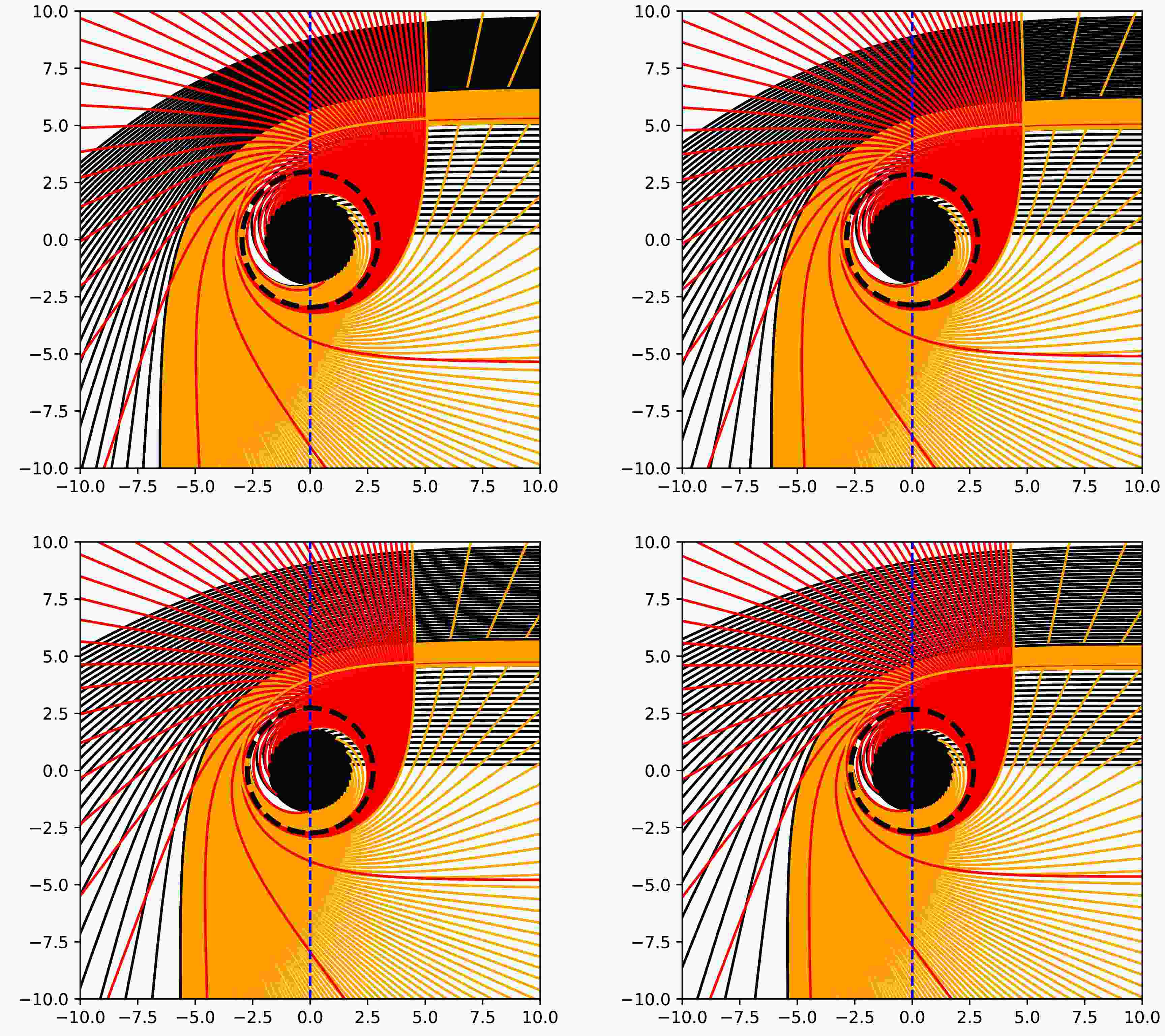

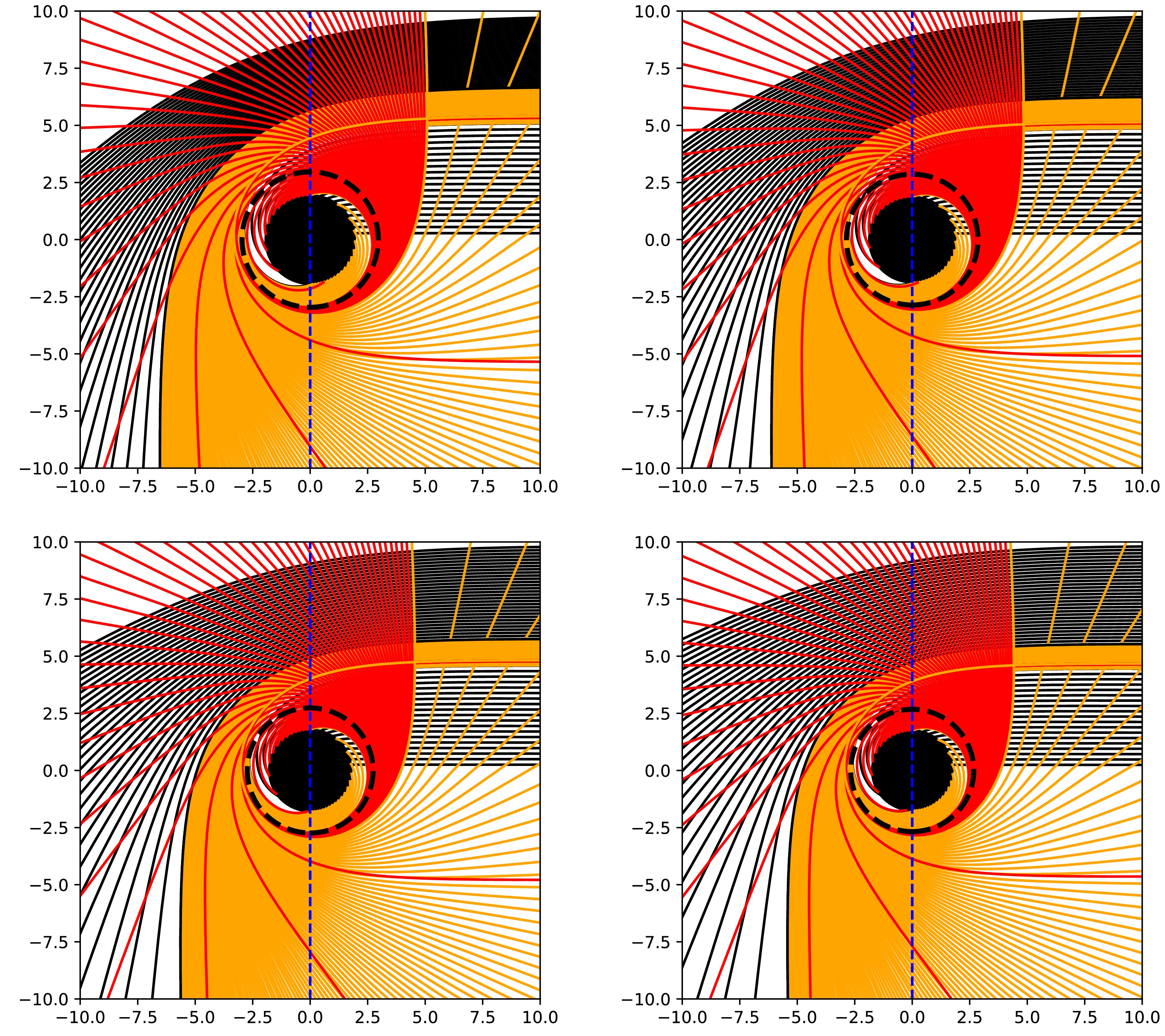

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ in Fig. 8.

Figure 8. (color online) Null geodesic diagrams of photons in polar coordinates for different values of the hair parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ :$ -0.07 $ (top-left),$ -0.04 $ (top-right),$ 0 $ (bottom-left), and$ 0.02 $ (bottom-right). The black disc represents the black hole region within the event horizon, and the black dashed line indicates the unstable photon sphere radius. The observer is located at the North Pole at a large distance from the black hole. The curved lines depict photon geodesic trajectories, with colors indicating their types: black for geodesics intersecting the accretion disk once, orange for those intersecting twice, and red for those intersecting more than three times.Fig. 8 shows the following:

• The significance of the impact parameter in the figure is that it is the coordinate value corresponding to the null geodesic at a distant position when it is directed to the right (north pole), that is, the radial distance from the center of the black hole of the light ray received by the distant observer.

• Under different hairy parameter conditions, the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills and the RN black holes exhibit similar characteristics. The impact parameter intervals of the photon ring (represented by red curves) and the lensing ring (represented by orange curves) of both are relatively narrow, which can also be clearly observed from Table 1. In comparison, the impact parameter interval of the direct ring (represented by black curves) is relatively large and is composed of two mutually independent parts.

$ Q_{\rm YM} $

$ {b}_{1}^{-} $

$ {b}_{2}^{-} $

$ {b}_{2}^{+} $

$ {b}_{3}^{-} $

$ {b}_{3}^{+} $

$ r_{\rm h} $

$ r_{\rm ph} $

$ b_{\rm ph} $

$ r_{\rm isco} $

−0.07 2.8133 5.1852 5.4303 5.4983 6.8027 1.9523 2.9647 5.4459 5.8753 −0.04 2.7088 4.9470 5.1676 5.2257 6.3607 1.8843 2.8630 5.1811 5.6724 0 2.5792 4.6552 4.8476 4.8950 5.8452 1.8000 2.7369 4.8586 5.4198 0.02 2.5183 4.5192 4.6993 4.7122 5.61423 1.7603 2.6775 4.7093 5.3021 Table 1. Values of the impact parameter b, event horizon radius

$ r_{\rm h} $ , photon sphere radius$ r_{\rm ph} $ , critical impact parameter radius$ b_{\rm ph} $ , and minimum orbit radius$ r_{\rm isco} $ when the hairy parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ takes different values,$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.07,-0.04,0,0.02 $ , respectively.• As the Yang-Mills hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, it will cause the impact parameter intervals of the lensing and photon rings in the spacetime to decrease. Correspondingly, the relative brightness in these regions will also become slightly dimmer.• Under different hairy parameter scenarios, such a phenomenon will occur: As the impact parameter increases, the bending degree of the corresponding null geodesic gradually increases, reaches a maximum value at the position of the unstable photon sphere, and then gradually decreases. During this process, its color change follows the rule of black

$ \rightarrow $ orange$ \rightarrow $ red$ \rightarrow $ orange$ \rightarrow $ black.• With the increase in the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ , the event horizon, photon sphere radius, and critical impact parameter of the corresponding black hole will all change (gradually decrease), and the shadow area of the black hole will also decrease.Therefore, the influence of the hairy parameter on photon trajectories cannot be ignored, and this characteristic can serve as a way to distinguish different black hole solutions.

After further calculations, the intervals corresponding to the impact parameters with different numbers of intersections with the accretion disk are determined, and the results are listed in Table 1, which also shows the results of the black hole event horizon

$ r_{\rm h} $ , photon sphere radius$ r_{\rm ph} $ , critical impact parameter$ b_{\rm ph} $ , and innermost stable circular orbit$ r_{\rm isco} $ (it will be used later).$ r_{\rm isco} $ can be calculated as [40]$ r_{\rm isco}=\frac{3f(r_{\rm isco})f^{\prime}(r_{\rm isco})}{2(f^{\prime}(r_{\rm isco}))^{2}-f(r_{\rm isco})f^{\prime \prime}(r_{\rm isco})}, $

(29) where the prime denotes the derivative with respect to r.

-

In this section, we focus on the simulation research of optical characteristics, total light intensity received by the observer, and images of the photon ring and black hole shadow observed by distant observers when the hairy parameter takes different values. As mentioned earlier, if the accretion disk is considered the only light source, for the null geodesics that intersect with the accretion disk, the light emitted from the accretion disk will propagate along these null geodesics to the position of the observer. Energy can be considered to be extracted each time the null geodesic intersects with the thin accretion disk. The more intersections occur, the more energy is extracted, and correspondingly, the brightness will increase, resulting in different contributions to the total intensity of the observed light, which directly affects the distribution of the observed intensity.

Because the thin accretion disk emits isotropically within the static frame, the specific intensity of the emission frequency

$ \nu_{e} $ received by the observer is [40]$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} I_0 (r, \nu_0) = g^3 I_e (r, \nu_e) \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(30) Here,

$ g =\dfrac{\nu_0}{\nu_e} = \sqrt{f(r)} $ is the redshift factor, with$ \nu_0 $ and$ \nu_e $ representing the frequencies of the observed and emitted light, and$ I_0(r, \nu_0) $ and$ I_e(r, \nu_e) $ the specific intensities of the observed and emitted light, respectively. The total observed intensity over the entire wavelength band can be obtained by integrating$ I_0 (r, v_0) $ over different frequency bands:$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} I_{\rm obs}(r) = \int I_0 (r, \nu_0) d\nu_0 = \int g^4 I_e (r, \nu_e) d\nu_e = f(r)^2 I_{\rm em}(r) \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(31) Among them,

$ I_{\rm em}(r) = \int I_e (r, \nu_e) {\rm d}\nu_e $ is the total emission intensity. Because the light extracts energy from the accretion disk each time they intersect, as we mentioned earlier, light rays with the number of orbital turns$ n > \dfrac{1}{4} $ will intersect with the accretion disk on the front side. When$ n > \dfrac{3}{4} $ , the light rays will bend around the black hole and intersect with the accretion disk for the second time on the back side. Furthermore, when$ n > \dfrac{5}{4} $ , the light rays will intersect with the accretion disk for the third time on the front side again, and the total intensity we observe should be the sum of the energy values extracted from each intersection [46, 65].$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} I_{\rm obs}(b) = \sum_m f(r)^2 I_{\rm em}(r) \Big|_{r = r_m(b)} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(32) Among them, we introduce the transfer function

$ r_m(b) (m = 1, 2, 3,\cdots) $ , changing its observed intensity to a function of b. It represents the radial coordinate of the m-th intersection of the null geodesic with impact parameter b and the accretion disk. The relationship between the number of intersections and total angle bypassed by the light ray is$ \varphi = \dfrac{2m - 1}{2} \pi $ (According to the backward ray tracing method, the so-called m-th intersection is named in the order of successive intersections of the null geodesic from the observer with the accretion disk). To simplify the calculation, we ignore the absorption and reflection of light rays by the accretion disk. Thereafter, when m is a fixed value, its slope$ \dfrac{{\rm d}r_m}{{\rm d}b} $ describes the demagnification factor, and a larger m corresponds to stronger demagnification.For the photon ring, a large strong demagnification occurs, and its contribution to the total observed light intensity can be ignored. The contribution of the photon ring to the total light intensity is only a few percent of that of the lensing ring; therefore, the total contribution of light intensity can be primarily attributed to the direct emission and lensing ring [46]. The first three transfer functions

$ r_m(b) (m = 1, 2, 3) $ can be expressed as$ r_1(b) = \frac{1}{u\left(\dfrac{\pi}{2}, b\right)}, \quad b \in (b_1^-, +\infty) , $

(33) $ r_2(b) = \frac{1}{u\left(\dfrac{3\pi}{2}, b\right)}, \quad b \in (b_2^-, b_2^+) , $

(34) $ r_3(b) = \frac{1}{u\left(\dfrac{5\pi}{2}, b\right)}, \quad b \in (b_3^-, b_3^+) . $

(35) Here,

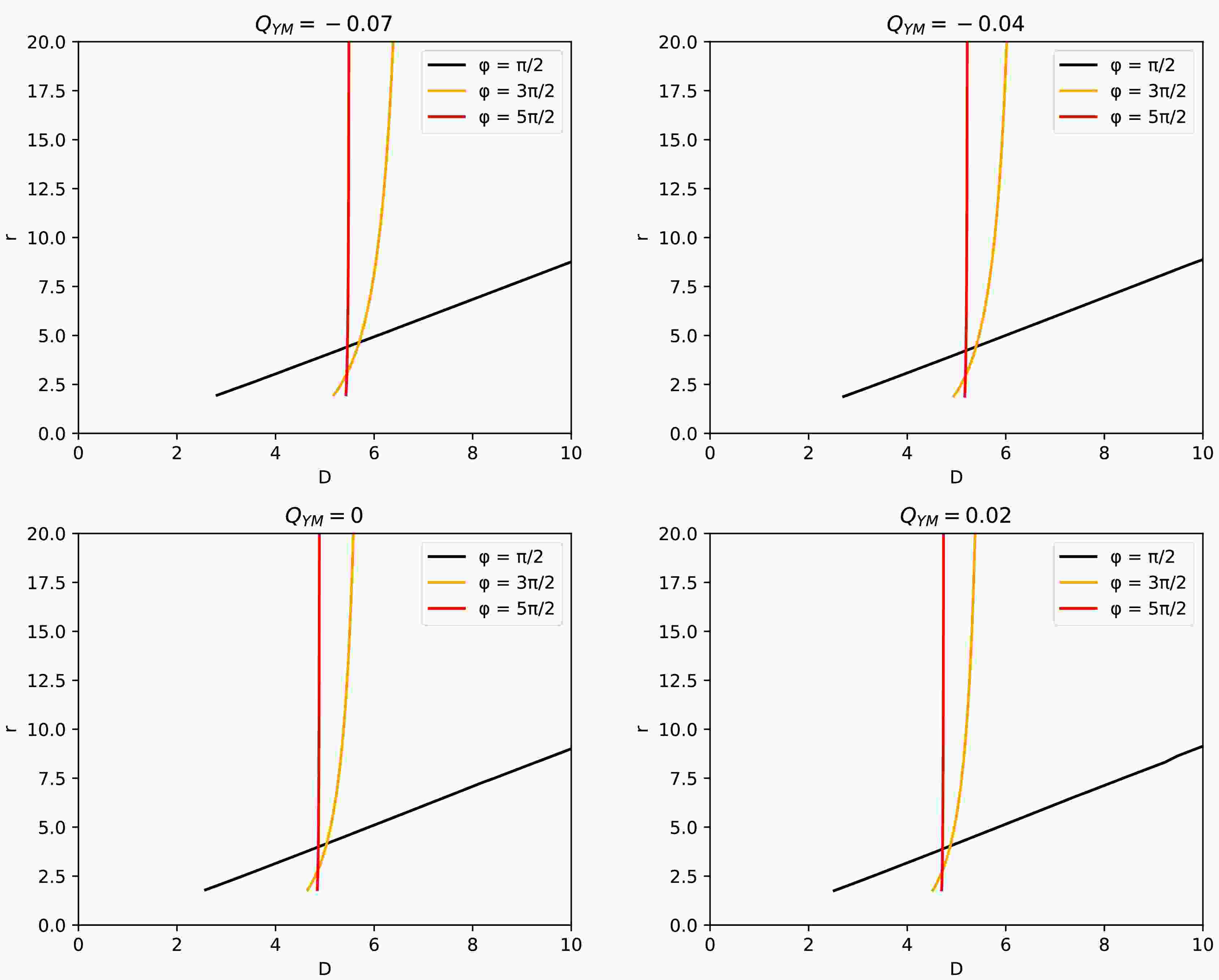

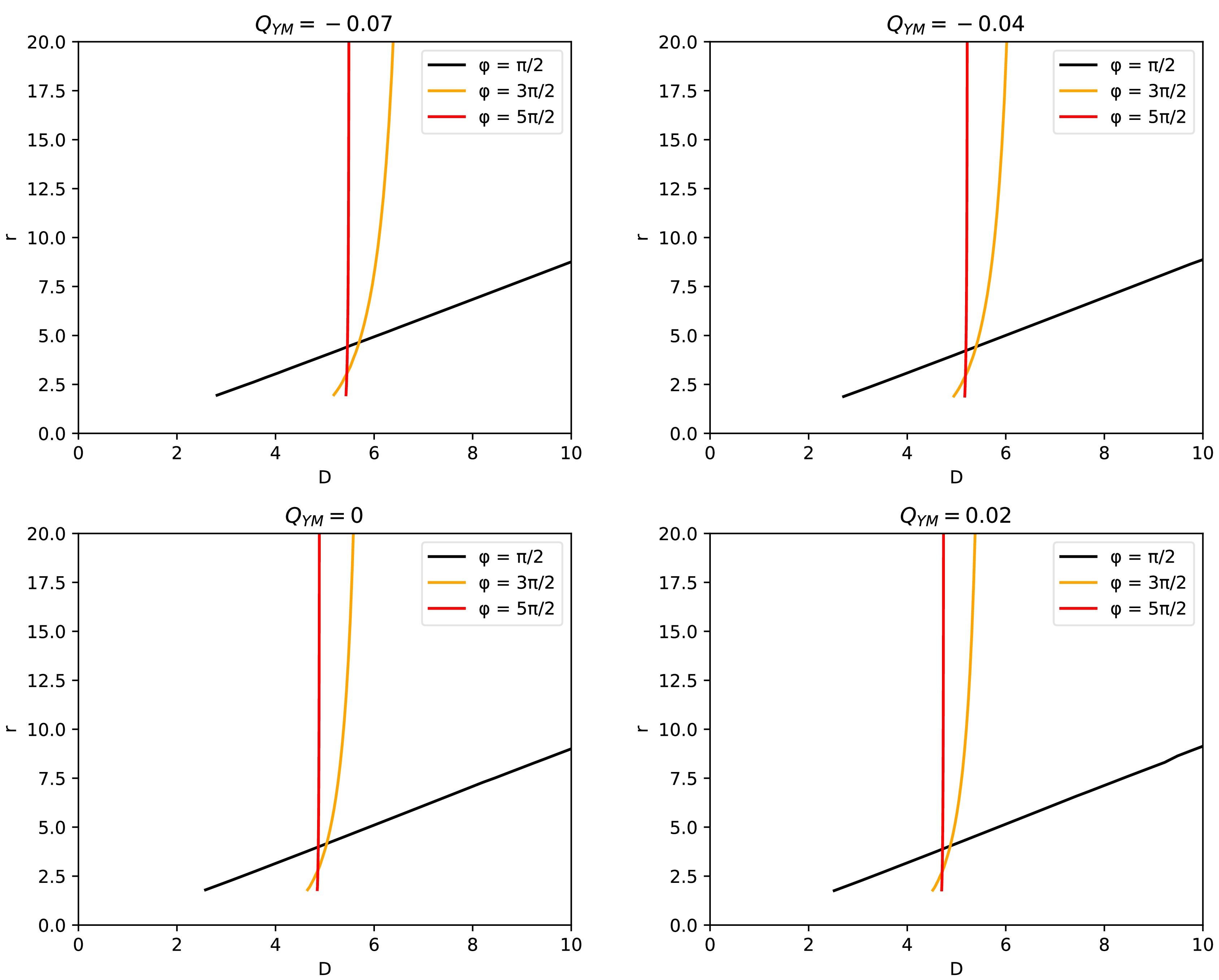

$ u(\varphi, b) $ is the solution to the photon geodesic, Eq. (17). We have plotted the graphs of the first three transfer functions for different values of the Yang-Mills hairy parameter in Fig. 9.

Figure 9. (color online) Images of the first three transfer functions for different values of the Yang-Mills hairy parameter, where the hairy parameters are taken as

$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.07 $ ,$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.04 $ ,$ Q_{\rm YM}=0 $ ,$ Q_{\rm YM}=0.02 $ . Black, orange, and red curves represent the radial coordinates of intersections with the accretion disk once, twice, and thrice, respectively.From the figure, we can draw the following properties:

• For the first transfer function (black curve), which can be obtained from direct emission, lensing rings, and photon rings, we find that as the Yang-Mills hairy parameter increases, the initial value of the impact parameter b decreases. Meanwhile, the slope of the black curve is close to 1, which means that the radial coordinate of the first intersection of the null geodesic with the accretion disk changes almost linearly with the impact parameter.

• For the second transfer function (orange curve), which can be derived from lensing and photon rings, we find that as the Yang-Mills hairy parameter increases, the value of the impact parameter b also decreases. The increase in the slope indicates that its contribution to the light intensity is relatively small.

• The third transfer function (red curve), which can only originate from the photon ring, has been studied, and we find that as the Yang-Mills hair parameter increases, the threshold of its collision parameter decreases, and the transfer function exhibits a larger slope. In terms of light intensity contribution, it is smaller than the second transfer function and can almost be ignored.

To further verify the prediction of the transfer function, we must conduct an in-depth study on the contributions of direct emission, lensing rings, and photon rings to the total intensity of the light and the optical appearance image of the observed Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole under specific emission intensity conditions. Hence, we have considered some specific toy model emission functions.

For the first emission model, we assume that the radiation intensity of the accretion disk is a function that decays in a quadratic power form starting from the innermost stable orbit.

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} I_{\rm em1}(r)=\begin{cases} I_{0}\left[\dfrac{1}{r-(r_{\rm isco}-1)}\right]^{2},&r > r_{\rm isco},\\ 0,&r\leq r_{\rm isco}. \end{cases} \end{split} \end{aligned} $

(36) Here,

$ I_{0} $ represents the maximum emission intensity (the same applies hereinafter). The data of the radius$ r_{\rm isco} $ of the innermost stable orbit is given in Table 1. In the first emission model, the intensity peaks at$ r_{\rm isco} $ before gradually decreasing to zero. In this case, the contribution of the lensing and photon rings to the observed flux is negligible, with no superposition occurring with direct emission [40]. When the emission peaks at$ r = r_{\rm ph} $ and$ r_{\rm h} $ , redshift effects significantly influence the observed flux [46]. Under these conditions, the lensing and photon rings superimpose with direct emission [46], producing observable bright ring structures distinct from the first model. To capture these differing optical signatures, we further employ$ I_{\rm em2} $ and$ I_{\rm em3} $ emission profiles.For the second emission model, we assume that the radiation intensity of the accretion disk is a function that decays in a cubic power form starting from the position of the photon sphere orbit.

$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} I_{\rm em2}(r)=\begin{cases} I_{0}\left[\dfrac{1}{r-(r_{\rm ph}-1)}\right]^{3}, & r > r_{\rm ph},\\ 0, & r \leq r_{\rm ph}. \end{cases} \end{split} \end{aligned} $

(37) Here,

$ r_{\rm ph} $ represents the photon sphere radius. For the third emission model, we consider a more slowly decaying function that starts from the position of the event horizon radius$ r_{\rm h} $ :$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} I_{\rm em3}(r)=\begin{cases} I_{0}\dfrac{\dfrac{\pi}{2}-\arctan \left[r-(r_{\rm isco}-1)\right]}{\dfrac{\pi}{2}-\arctan \left[r_{\rm h}-(r_{\rm isco}-1)\right]}, & r > r_{\rm h},\\ 0, & r \leq r_{\rm h}. \end{cases} \end{split} \end{aligned} $

(38) Because the real universe has various substances surrounding black holes, the observational images must be further studied under different circumstances. Therefore, we substitute these three different emission intensity and transfer functions into Eq. (32) to study the total emission and the total observed intensity under the three toy models when the Yang-Mills hairy parameter has values of

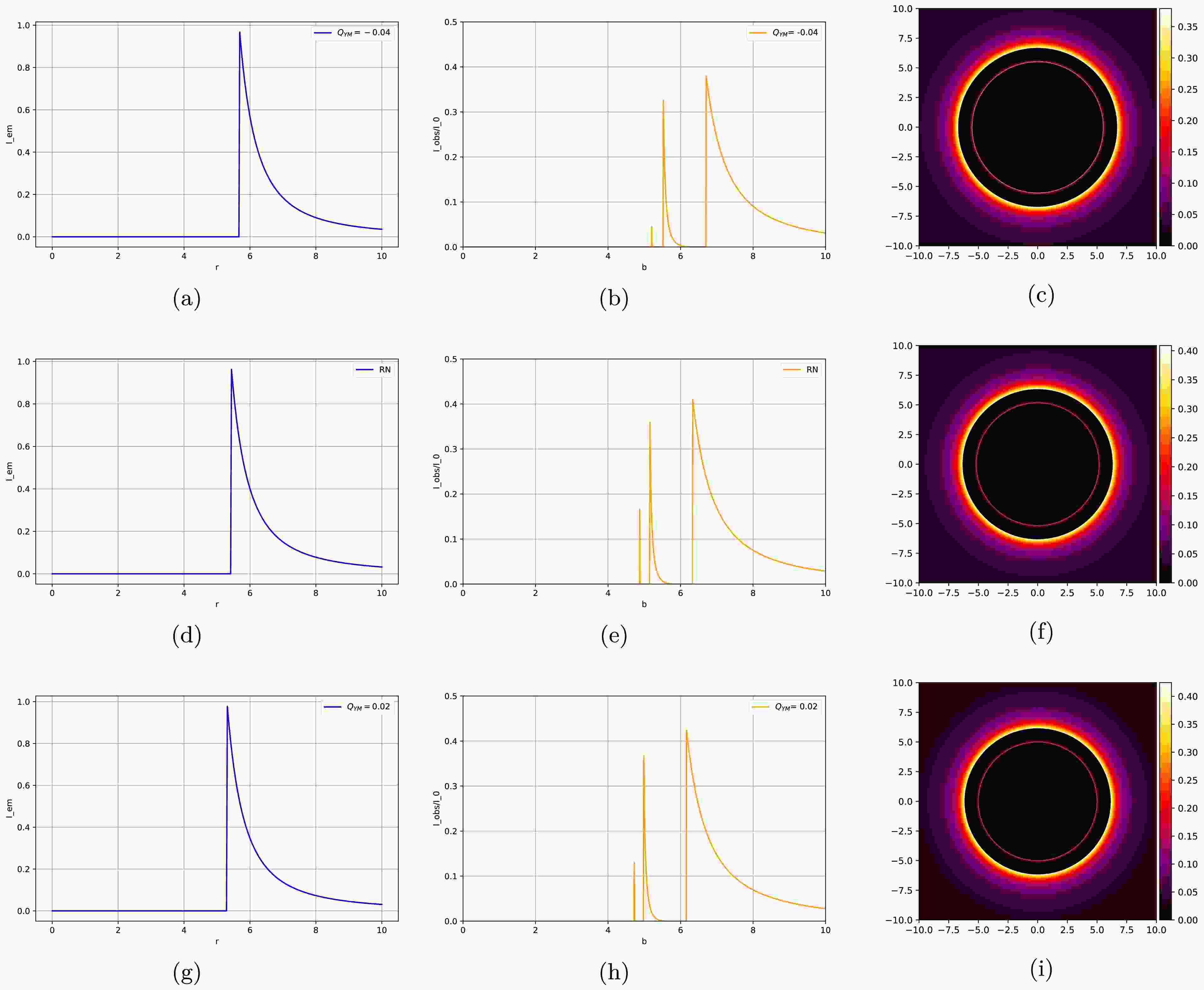

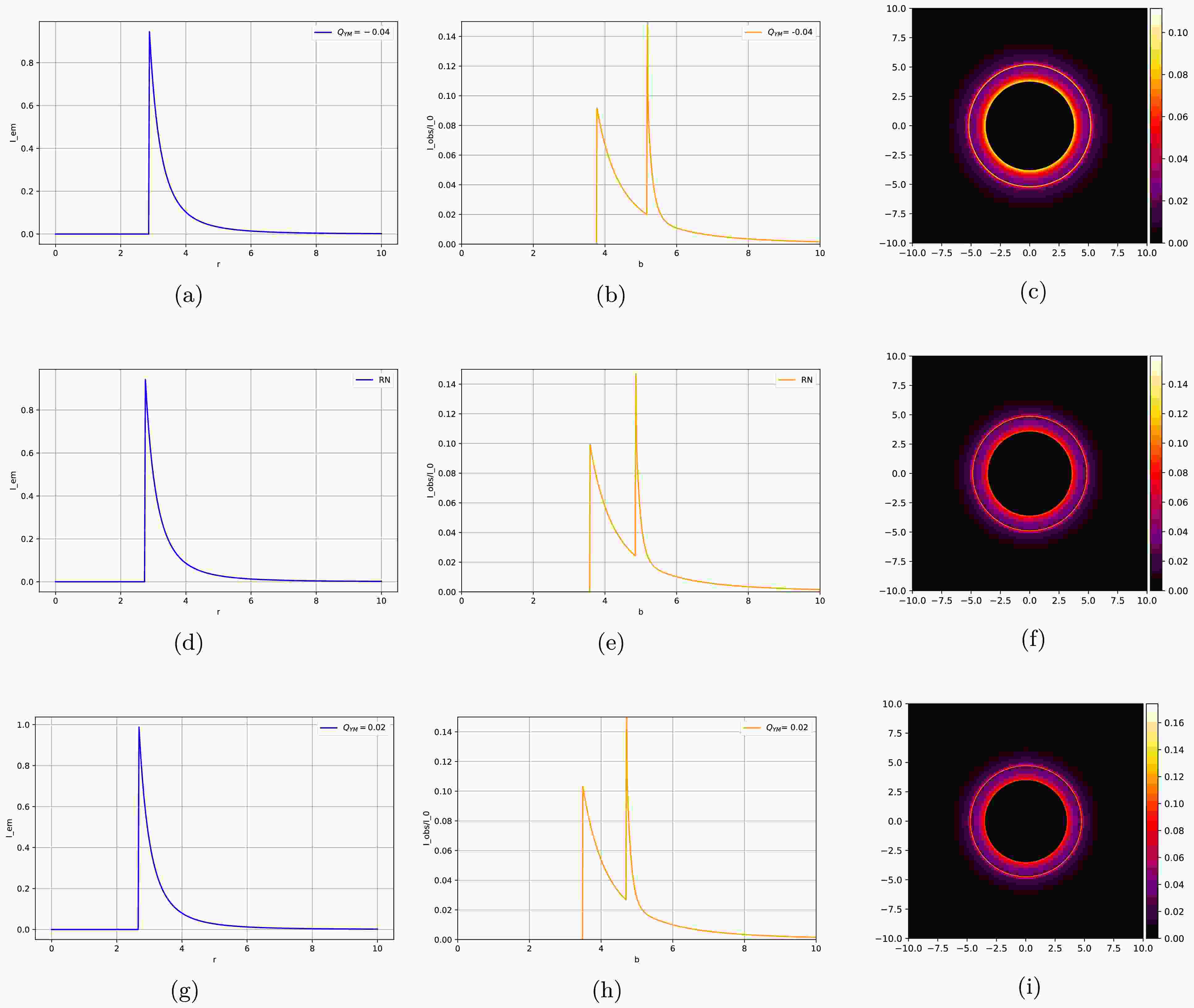

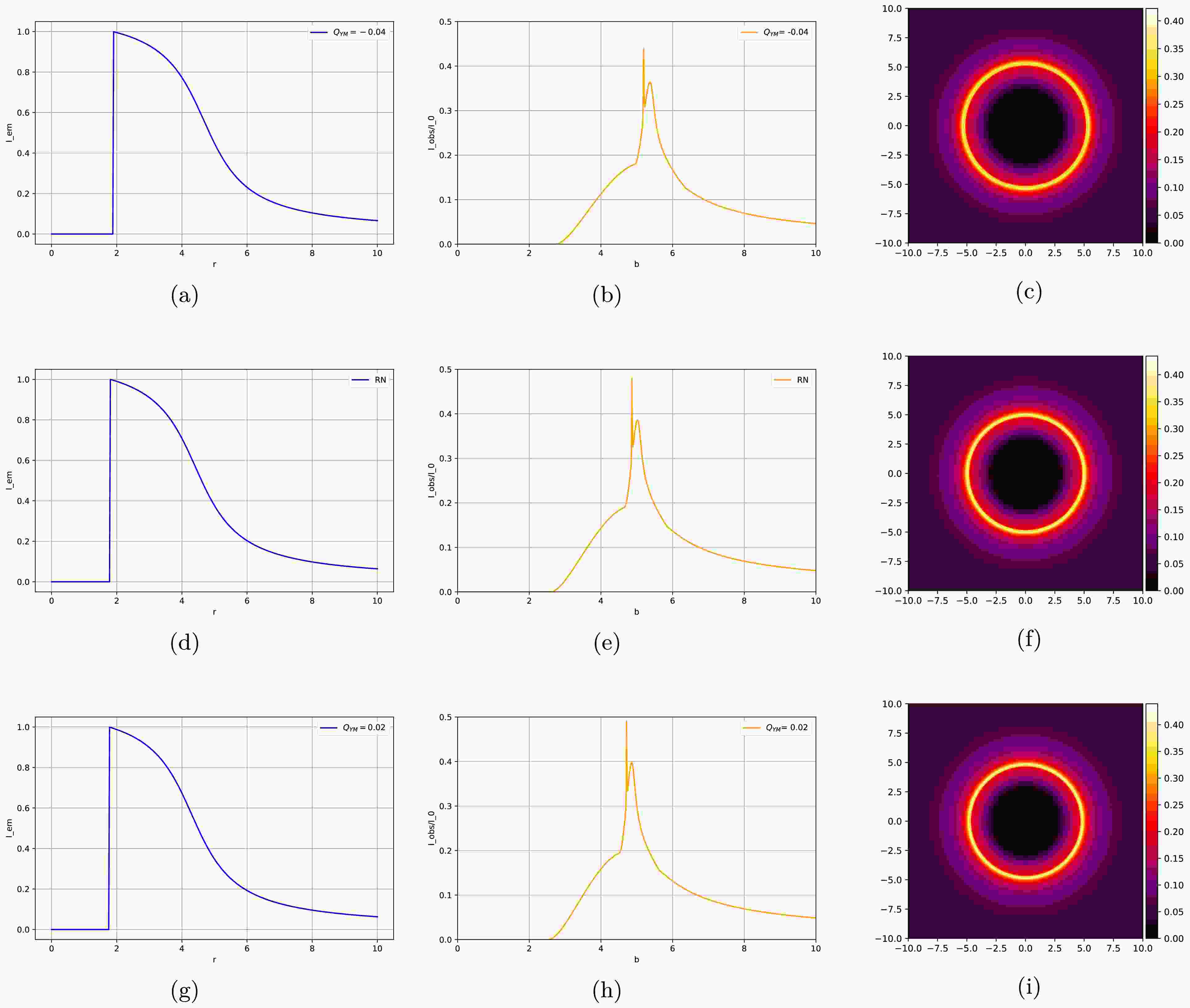

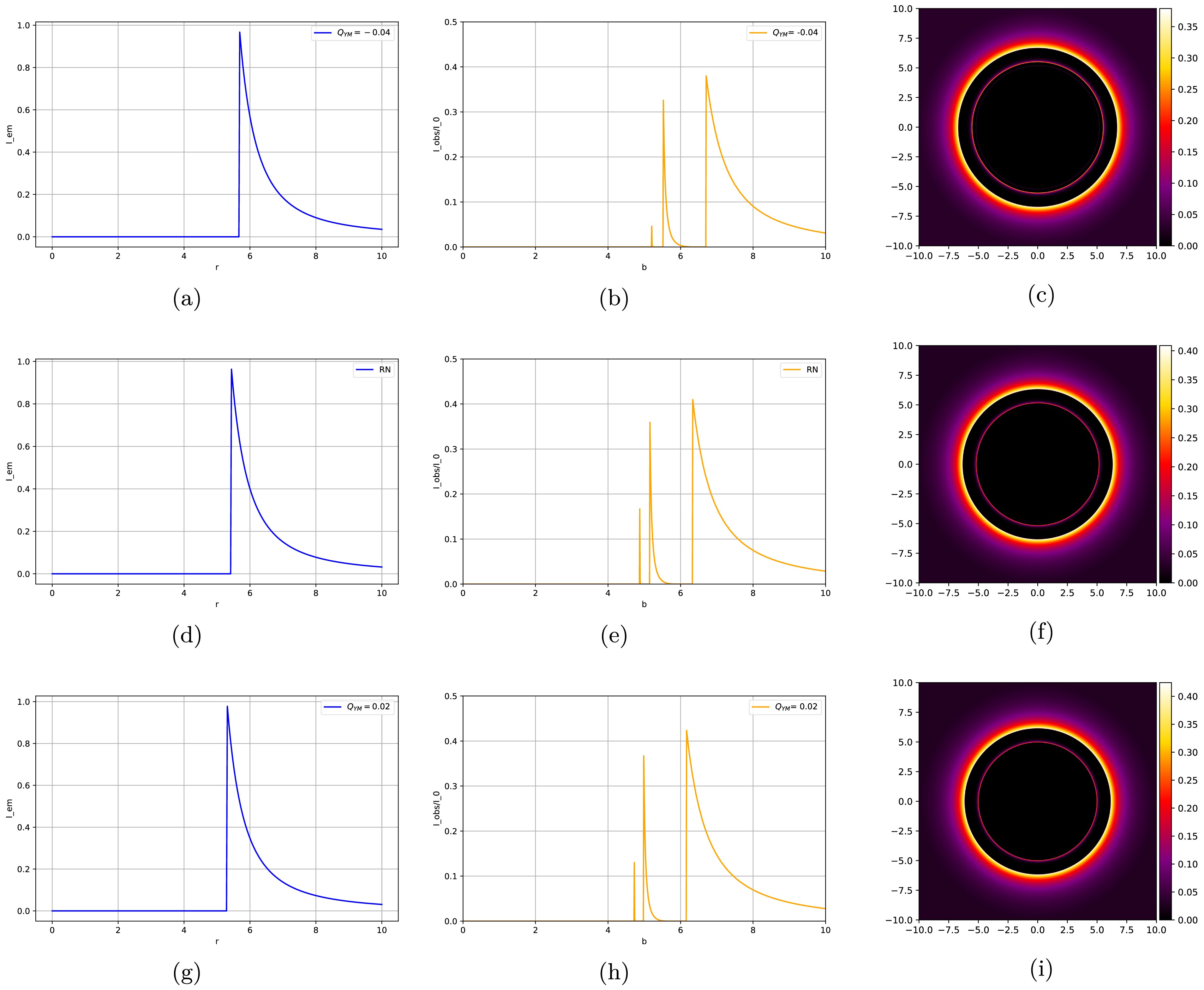

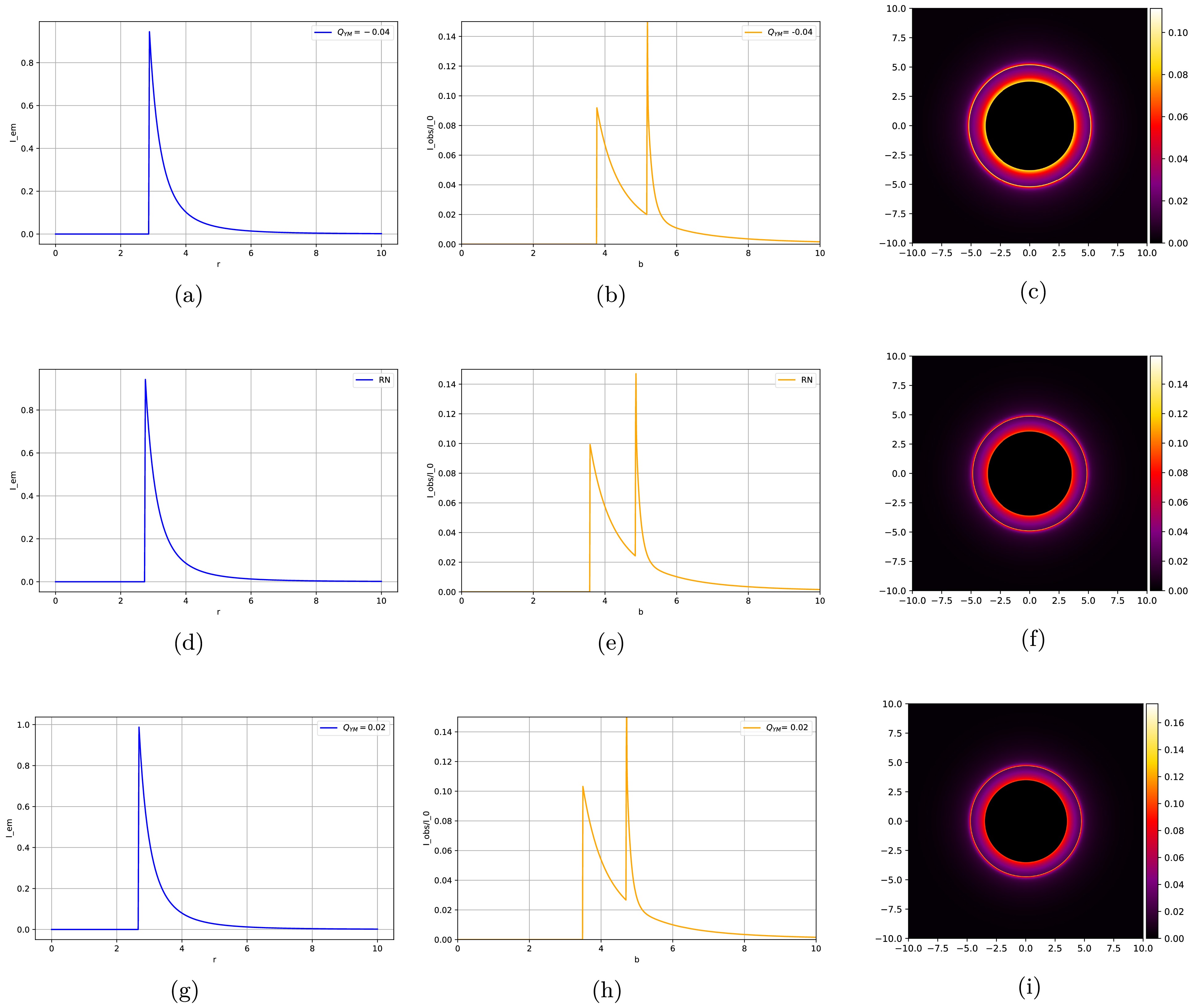

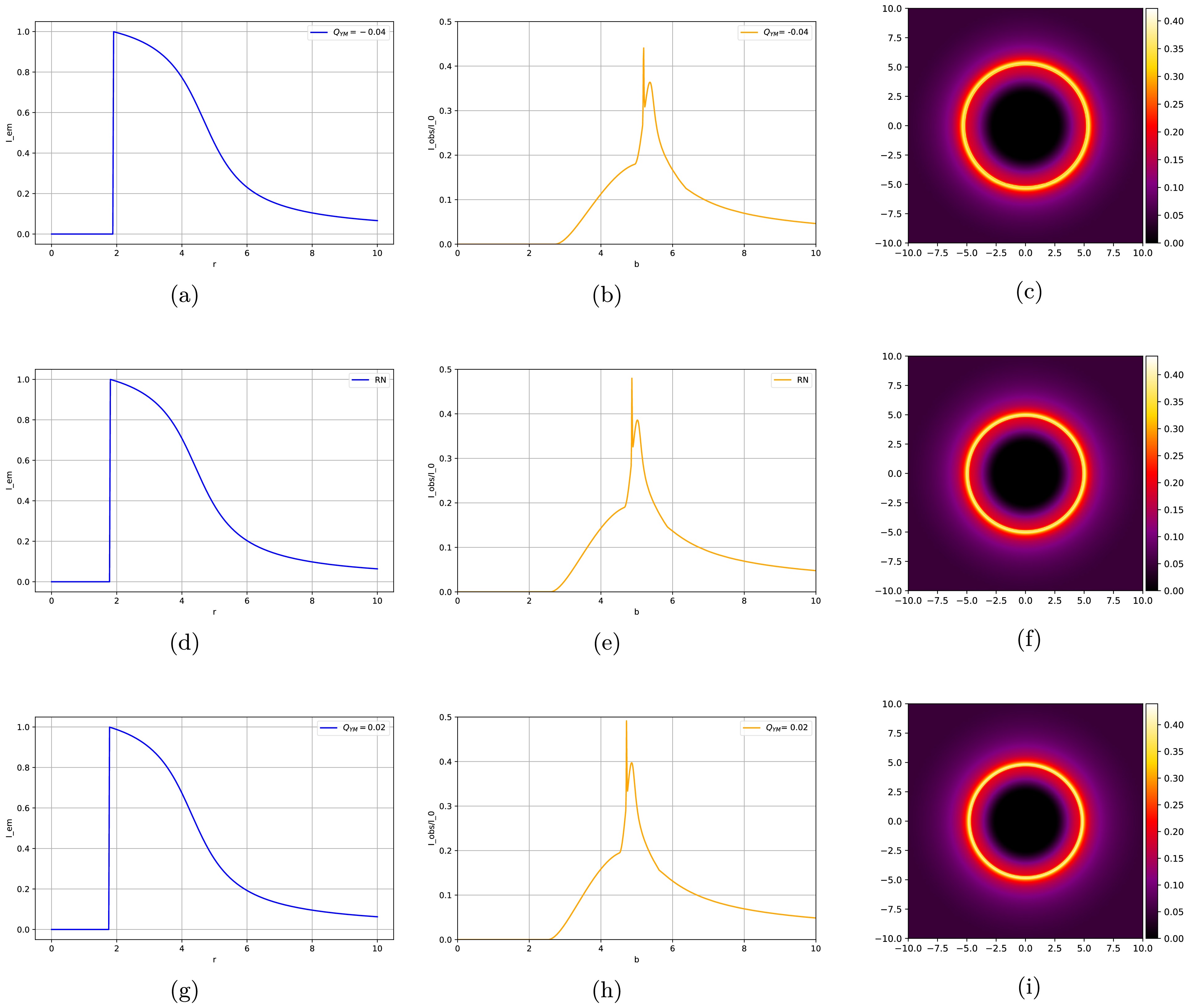

$ -0.04 $ ,$ 0 $ , and$ 0.02 $ , as well as their optical appearances (see Figs. 10, 11, and 12). The first column of each figure shows the total emission intensity, and the second column displays the total observed intensity, that is, the contributions of the three ring structures to the total light intensity. The third column presents the variation in the total observed intensity with the impact parameter and converts it into the corresponding two-dimensional image, thus generating the optical appearance of the accretion disk.

Figure 10. (color online) Images of the first toy model when the Yang-Mills hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ takes values of$ -0.04 $ ,$ 0 $ , and$ 0.02 $ . The first column shows the emission intensity$ I_{\rm em1}(r) $ , second column presents the total intensity$ I_{\rm obs}(b) $ observed by the observer, and third column displays the optical appearance seen by the observer.

Figure 11. (color online) Images of the second toy model when the Yang-Mills hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ takes values of$ -0.04 $ ,$ 0 $ , and$ 0.02 $ . The first column shows the emission intensity$ I_{\rm em2}(r) $ , the second column presents the total intensity$ I_{\rm obs}(b) $ observed by the observer, and the third column displays the optical appearance seen by the observer.

Figure 12. (color online) Images of the second toy model when the Yang-Mills hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ takes the values of$ -0.04 $ ,$ 0 $ , and$ 0.02 $ . The first column shows the emission intensity$ I_{\mathrm{em3}}(r) $ , second column presents the total intensity$ I_{\rm obs}(b) $ observed by the observer, and third column displays the optical appearance seen by the observer.Fig. 10 shows the emission and reception intensities and the optical appearance of the first toy model:

• In the first toy model, the emission intensity in the first column exhibits a specific pattern: it reaches its maximum value at the radius

$ r_{\rm isco} $ of the innermost stable circular orbit and then decays rapidly. Moreover, as the hairy parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ continuously increases, the peak of the emission intensity moves in the direction of decreasing b value. Therefore, when the Yang-Mills hairy parameter increases, the minimum radius of photons around the black hole decreases accordingly.• Regarding the total intensity observed by the observer in the second column, as shown in figure (b), the three peaks from left to right are the photon, lensing, and direct rings. However, the region of the photon ring is extremely narrow, which can be observed in figure (b). As the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, the peak of the ring moves in the direction of decrease. Therefore, in the optical appearance diagrams with larger values of$ Q_{\rm YM} $ , the radius of the ring we observe is smaller. The photon ring's emission peak becomes virtually undetectable, rendering its contribution to the total observed flux negligible. The bimodal distribution of the observed intensity implies that its two-dimensional projection should exhibit dual bright rings. This characteristic morphology is unambiguously demonstrated in the corresponding optical image (third column).• The dark area in figure (c) in the third column has a very thin bright ring, which is the lensing ring. An even thinner photon ring exists on the inner side of the lensing ring. Its brightness is too low to be easily observed, and the contributions of these two rings to the overall brightness are extremely limited. The direct emission is located outside the lensing ring. At the position of the direct emission, the brightness suddenly increases and becomes extremely bright. Subsequently, the brightness gradually decreases as it moves further outwards.

• In conclusion, under different hairy parameters

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ , the positions of the peak values of the total intensity observed by the observer will change. As the Yang-Mills hairy parameter continuously increases, the peak of the observed total intensity moves in the direction of decreasing b, which causes the radius of the optical appearance to change accordingly. In the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole, precisely because of this characteristic, no degeneracy phenomenon occurs in its optical appearance images. Note that the values of the Yang-Mills hair corresponding to the photon rings with different radius in the optical appearance of this black hole are different. This rule provides an effective means to test the Yang-Mills hair, which is conducive to our further exploration of the physical phenomena and essence related to this black hole.The emission and reception intensities and the optical appearance of the second toy model are shown in Fig. 11:

• In the first column, the emission intensity of the second toy model reaches its maximum value at the photon sphere

$ r_{\rm ph} $ , and then decays rapidly. Moreover, as the Yang-Mills hairy parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, the peak moves in the direction of decreasing b. That is, an increase in the Yang-Mills hairy parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ can reduce the radius of the photon sphere of photons around the black hole.• For the total intensity observed by the observer in the second column, as in (b), the two peaks from left to right are, respectively, a peak formed by the direct ring and another peak formed by the superposition of the photon and lensing rings. Unlike the first model, the direct ring appears inside the lensing and photon rings. As

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, the peaks of the rings also move in the direction of decreasing b. Therefore, the radius of the rings observed in the optical appearance diagrams with larger values of$ Q_{\rm YM} $ will also be smaller.• Judging from the total observed intensity presented in the second column, the total observed intensity is decreasing compared with the first toy model. This can also be observed from the optical appearance in the third column. Consequently, the optical appearance also appears relatively darker. In addition, the brighter direct ring is located inside the photon and lensing rings.

Figure 12 shows the emission and reception intensities as well as the optical appearance of the third toy model:

• The emission intensity of the third toy model in the first column reaches its maximum value at the radius of the event horizon

$ r_{\rm h} $ and then decays slowly. Moreover, as the Yang-Mills hairy parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, the peak value b shifts in the decreasing direction. In other words, the same result also holds for the third toy model: an increase in the hairy parameter$ Q_{\rm YM} $ can reduce the photon sphere radius of photons around the black hole.• From figure (b) of the total observed intensity for the observer in the second column, we observe an obvious peak, which appears at the position of the photon ring, indicating that the intensity of the photon ring plays a decisive role in the maximum value of the total observed intensity. As

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, a second peak appears at the position of the lensing ring. The difference in the intervals between these two peaks shows that the lensing ring contributes more to the total flux than the photon ring. Compared with the second toy model, the observed intensity is slightly enhanced. As$ Q_{\rm YM} $ increases, the peak gradually becomes stronger, and the position of the peak shifts in the direction of decreasing b. Therefore, the radius of the ring observed in the optical appearance diagram for larger values of$ Q_{\rm YM} $ will also be smaller.• Compared with the first and second models, the third model has only one ring that changes from dark to bright and then from bright to dark, whereas the first and second models have two rings. Moreover, due to the greater total observed intensity in the second column, the third model has a higher brightness. The third model should also have two rings. However, judging from the observed intensity and the image, the distance between the two peaks is too small; therefore, discerning the double-ring structure is very difficult.

In conclusion, the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ has an impact on the observed intensity under different models. The larger the hairy parameter, the stronger the observed intensity. Different hairy parameters also affect the position of the peak of the observed intensity, thus influencing the optical appearance image. Therefore, these results can serve as effective characteristics for distinguishing black holes with different hairy parameters. -

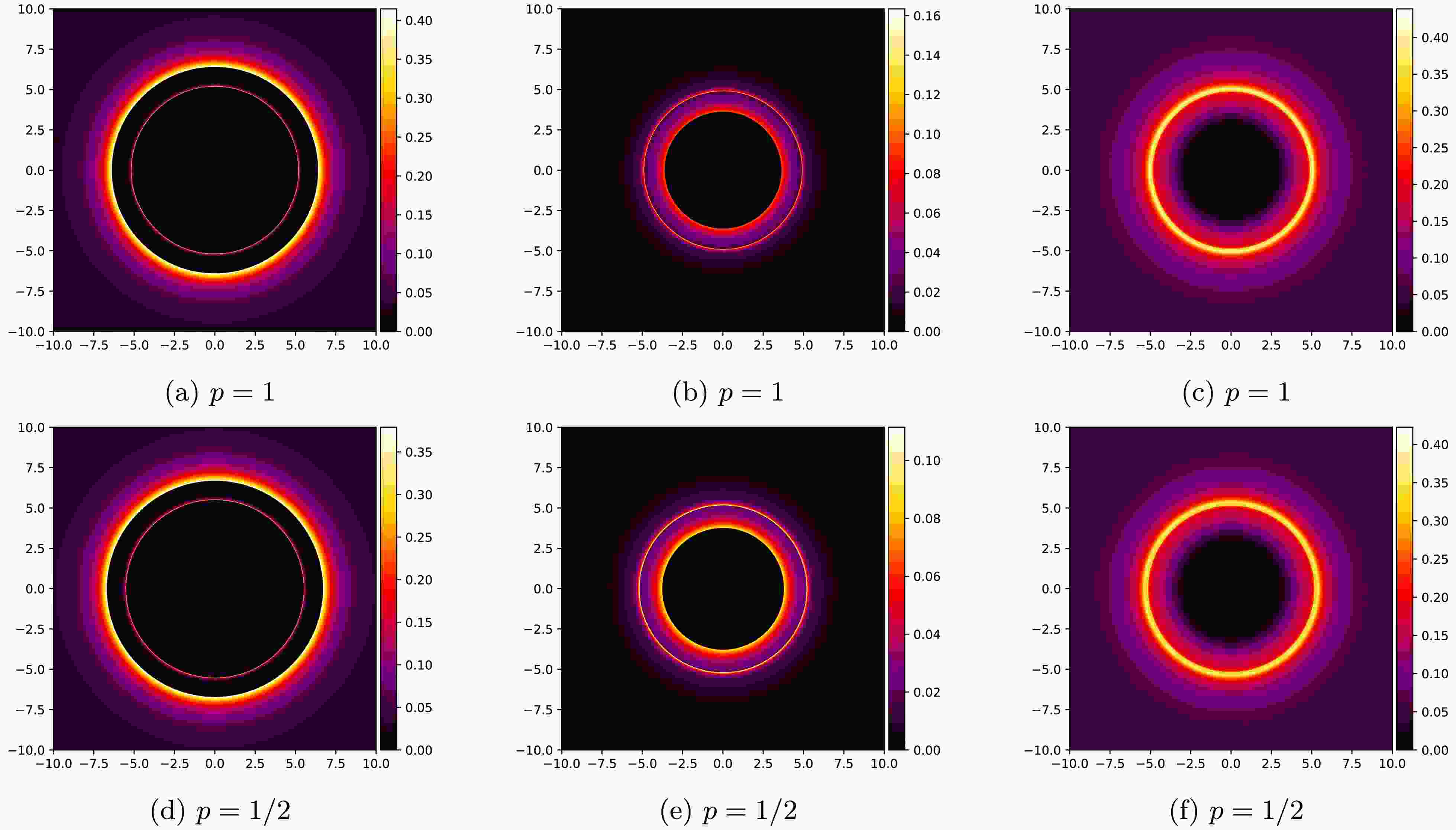

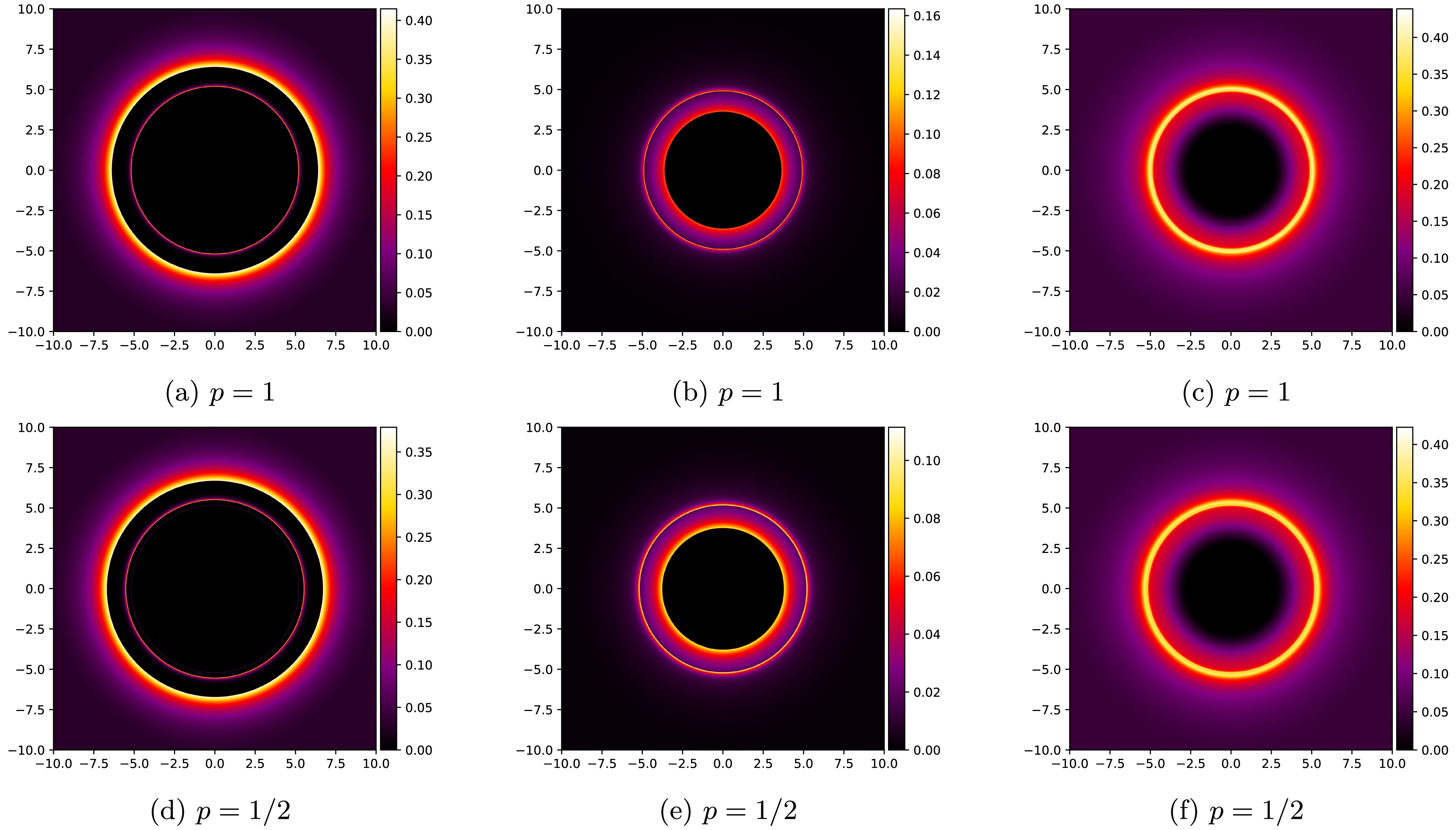

In this subsection, to highlight the distinctive features of the Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole with

$ p=1/2 $ , we compare its optical appearance with that of the standard Yang-Mills black hole ($ p=1 $ ) under identical parameters$ Q=0.6 $ and$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.04 $ . The metric function for the standard case is obtained by setting$ p=1 $ in Eq. (5):$ \begin{aligned} \begin{split} f_{\text{std}}(r)=1 - \frac{2M}{r}+\frac{Q^{2}}{r^{2}}+\frac{Q_{\rm YM}}{r^{2}} \end{split}. \end{aligned} $

(39) In this case, the contribution of the Yang-Mills term shares the same form as the Maxwell term. Consequently, the geometric properties of the black hole (such as the event horizon radius and photon sphere radius) exhibit behavior similar to that of an RN black hole, with the total charge term effectively becoming

$ Q^{2}+Q_{\rm YM} $ . Under these conditions, the optical appearance and photon ring structure of the black hole will resemble those of an RN black hole, although specific numerical values will be adjusted owing to the inclusion of the$ Q_{\rm YM} $ parameter. Table 2 presents the comparative parameter values between the standard Yang-Mills black hole ($ p=1 $ ) and the power-law Yang-Mills black hole ($ p=1/2 $ ) with fixed charge parameters$ Q=0.6 $ and$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.04 $ . The term "Relative Enhancement" refers to the relative increase in relevant physical parameters of power-law Yang-Mills black holes compared to standard Yang-Mills black holes. We find that under identical parameter conditions, the various characteristic radii (e.g., event horizon radius$ r_{\rm h} $ , photon sphere radius$ r_{\rm ph} $ ) of power-law Yang-Mills black holes exhibit an increase compared with those of standard Yang-Mills black holes.Parameter Standard Yang-Mills ( $ p=1 $ )

Power-law Yang-Mills ( $ p=1/2 $ )

Relative Enhancement $ r_{\rm h} $

1.8246 1.8843 +3.27% $ r_{\rm ph} $

2.7688 2.8630 +3.40% $ b_{\rm ph} $

4.8991 5.1811 +5.76% $ r_{\rm isco} $

5.4889 5.6724 +3.34% Table 2. Comparison of characteristic parameters between the standard Yang-Mills black hole (

$ p=1 $ ) and power-law Yang-Mills black hole ($ p=1/2 $ ) with fixed parameters$ Q=0.6 $ and$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.04 $ .The power-law Yang-Mills case exhibits systematically larger values compared with those of the standard Yang-Mills solution, reflecting the nonlinear geometric effects induced by the

$ r^{4p-2} $ term. To verify the observational effects induced by the parametric differences discussed above, Fig. 13 presents a comparative analysis of the optical appearance characteristics between the standard Yang-Mills black holes and the power-law Yang-Mills black holes under three representative emission models.

Figure 13. (color online) Optical appearance comparison between (a-c) standard (

$ p=1 $ ) and (d-f) power-law ($ p=1/2 $ ) Yang-Mills black holes with$ Q=0.6 $ and$ Q_{\rm YM}=-0.04 $ . Columns represent three distinct emission models.As shown in Fig. 13, the optical appearance between the power-law Yang-Mills and standard Yang-Mills black holes is significantly different: the photon ring radius of the former is slightly larger, which is consistent with the parameter calculation results presented earlier. The introduction of the power-law term leads to changes in all relevant optical parameters. This result indicates that the power parameter not only affects the spacetime structure of the black hole but also plays an important role in the imaging and observation of the shadow of the Einstein Maxwell power-Yang-Mills hairy black hole. This exhibits characteristics consistent with those observed in the uncharged power-law Yang-Mills black holes studied in the literature [56].

-

In this paper, the null geodesics near the Einstein Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole are studied. Moreover, based on the distribution of light rays, the optical images of the black hole surrounded by an optically and geometrically thin accretion disk are calculated, and the influence of the hairy parameter on both is discussed.

First, the Einstein Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole solution is briefly reviewed. In this solution, a p-power Yang-Mills term and hairy parameter related to non-Abelian charge are introduced, and the influence of the hairy parameter on the radius of the event horizon is analyzed. By analyzing the change in the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ when$ Q=0.6 $ , we find that a critical scenario occurs for the black hole when$ Q_{\rm YM}=1.77778 $ ; when$ Q_{\rm YM}< 1.77778 $ , the Einstein Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black hole has two horizons, corresponding to the Cauchy and event horizons; when$ Q_{\rm YM}>1.77778 $ , no event horizon exists, and it is a naked singularity scenario. Owing to the cosmic censorship hypothesis proposed by Penrose, which prohibits the appearance of naked singularities, in this paper, we primarily consider the case where$ Q_{\rm YM}< 1.77778 $ .Second, the equations of motion trajectories and the effective potential of photons around this black hole are studied. Starting from the Lagrangian of the black hole, the geodesic equations and the effective potential of photons are obtained. The radius of the unstable photon sphere orbit can be determined based on the effective potential. Subsequently, the null geodesics around the hairy black hole are explored through the backward ray-tracing method. We find that the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ has an impact on both the distribution and classification of geodesics. Moreover, when the hairy parameter increases, the event horizon radius$ r_{\rm h} $ , photon sphere radius$ r_{\rm ph} $ , radius of the innermost stable circular orbit$ r_{\rm isco} $ , and critical impact parameter$ b_{\rm ph} $ of the black hole would all decrease. The interval of the impact parameters corresponding to the photon and lensing rings would also become narrower, which would further affect the image of the null geodesics of the black hole. The data and images are depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 8, respectively.Finally, we investigate the total emission intensity, total observed intensity, and corresponding optical appearance for each of the three simplified models with varying values of the hairy parameter

$ Q_{\rm YM} $ under the illumination of an optically and geometrically thin accretion disk. The results demonstrate that as the hairy parameter increases, the total observed intensity of each model is enhanced, with all intensity peaks shifting toward decreasing values of the impact parameter b, leading to a reduction in the light ring radius. Furthermore, all three emission models reveal that: (i) the direct image dominates the total flux, (ii) the lensing ring manifests as a bright yet extremely narrow structure that is challenging to observe, and (iii) the contribution of the photon ring is negligible and virtually undetectable. Our conclusions indicate that distinct hairy parameters yield differentiable optical signatures, which exhibit no degeneracy with the optical characteristics of standard RN black holes and can thus be distinguished from them. Additionally, for identical values of the hairy parameter, we conduct a comparative analysis between the optical appearance in the nonlinear regime ($ p=1/2 $ ) and the standard Yang-Mills case ($ p=1 $ ). The results demonstrate that the optical appearance of the nonlinear p-power Yang-Mills black hole is dimmer than the standard case while exhibiting a larger shadow radius and brighter ring radius relative to the standard scenario. Consequently, the optical appearance of black holes may serve as a viable tool for discriminating between spacetime metrics of Einstein-Maxwell power-Yang-Mills black holes with different hairy parameters. This provides a potential avenue for characterizing distinct black hole solutions through future observations of photon rings, thereby offering valuable insights and research directions for probing the fundamental nature of black holes. Note that in this work, our focus has been on photon rings of static spherically symmetric black holes. However, because actual astrophysical black holes typically possess angular momentum, significant research efforts have been devoted to studying the photon rings of rotating black holes [66−68]. These considerations motivate our future investigations into the optical characteristics of these physically significant rotating black hole systems. -

We acknowledge the anonymous referee for a constructive report that has significantly improved this paper.

Testing Einstein-Maxwell Power-Yang-Mills hair via black hole photon rings

- Received Date: 2025-07-07

- Available Online: 2026-01-15

Abstract: In this paper, the optical appearance of static and spherically symmetric hairy black holes is studied under the standard Einstein-Maxwell theory considering the p-power Yang-Mills term. During the research process, the specific case of

Abstract

Abstract HTML

HTML Reference

Reference Related

Related PDF

PDF

DownLoad:

DownLoad: